An ocean apart, similar stories: US protests hit home in South Africa

| Johannesburg

His family says they watched as he was held down and choked inside his own house here, slammed against a concrete wall and beaten with fists and the butt of a gun. Collins Khosa’s partner Nomsa Montsha screamed for the officers to stop, but they beat her too. Three hours later, as he lay on their bed holding her hand, she watched her husband die of what a postmortem would later clinically label a “blunt force head injury.”

It was a similar scene that has caused hundreds of American cities and towns to erupt in anguish and rage over the past week. Much like in the killing of George Floyd, Mr. Khosa, who died on April 10, was also a black man alleged to have committed a minor crime. Like in the United States, his attackers were law enforcement.

U.S. protests over the killing of Mr. Floyd and other black Americans, like EMT Breonna Taylor, have inspired a cascading global reaction. And it feels particularly familiar here in South Africa, where, as in the U.S., policing was historically used to maintain white supremacy. There has been both an outpouring of solidarity, and sharp calls to turn inward, to consider why violent policing of poor black South Africans remains common a generation after the end of apartheid.

Why We Wrote This

When you look at the U.S. protests, what do you see? For many South Africans, it’s a reminder of their own society’s complicated, continuing history of police violence. Both countries’ hard-won gains toward equal protection for all often seem stubbornly far off.

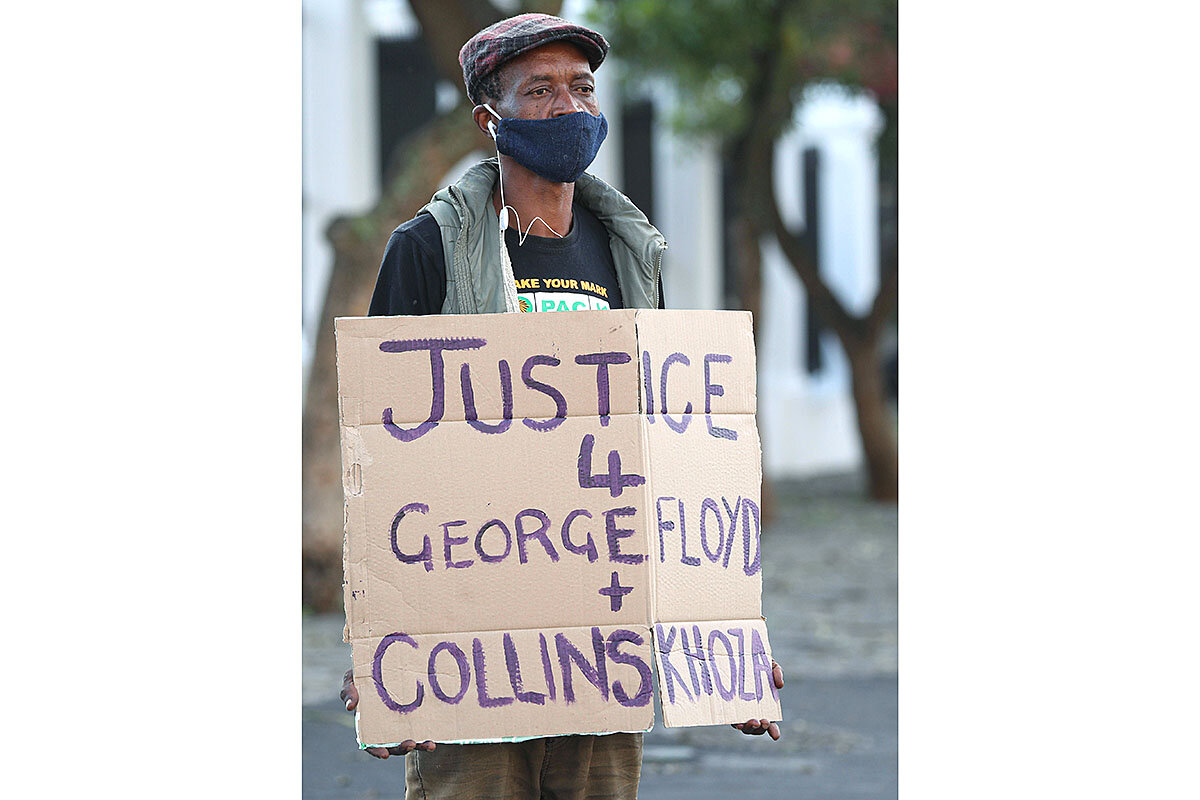

“The experience of police brutality is something extremely common to the black South African experience,” says Solomzi Henry Moleketi, who stood outside the U.S. Consulate in Johannesburg Thursday with a group of friends holding signs that read “Africans Stand With Black Lives Matter.” “When we talk about the killing of George Floyd and Collins Khosa, we’re speaking of a common struggle.”

The video of Mr. Floyd dying under the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin, he added, “ripped my soul.”

History’s shadow

In many ways, Mr. Floyd and Mr. Khosa came from similar worlds: societies with deeply seated racism, where being black meant being far more prone to die young, go to prison, and live in poverty. Mr. Floyd died in a commercial borderland between many of Minneapolis’ more affluent, mostly white neighborhoods and its poorer mostly black ones. Mr. Khosa, meanwhile, was killed in his home in Alexandra, a crowded, mostly poor black neighborhood in Johannesburg that brushes up against Sandton, the skyscraper suburb known as “Africa’s richest square mile.” Both men lived, and died, with their country’s gaping inequalities on full display.

Both, too, came of age in worlds where police violence against black people was part of the fabric of society. Mr. Floyd grew up in the 1980s, when victims of police violence had to prove that force was not applied in a “good faith effort” to stop a crime. (Today, courts require an officer’s use of force to be “objectively reasonable” in the situation he or she is in.) Mr. Khosa also grew up in the ‘80s, the dying years of apartheid, when police and soldiers patrolled black neighborhoods in armored vehicles. Dozens of activists were killed by police, and thousands, including many children and peaceful protesters, were killed by security forces.

But the years that followed, as apartheid ended and Nelson Mandela’s South Africa came to be seen as the global poster child for racial reconciliation, the country’s police force began to change too. The percentage of white cops fell, and top leadership flipped from white to black. Yet the government wrestled with how to transform a police service designed to maintain white rule, often violently, into one that served its entire population.

For the first decade of democracy, the police worked to “demilitarize,” says Kelly Gillespie, a South African anthropologist focused on criminal justice. But as violent crime continued to plague the country, more aggressive tactics returned.

Some black South Africans welcomed the hard-line stance, hoping it would reduce the violent crime that stalked many neighborhoods. But it was no coincidence that the targets of this new wave of police brutality were largely the same they had been under apartheid, Dr. Gillespie says, because the communities most aggressively targeted were poor areas, which are still almost exclusively black.

“Since apartheid, there’s been a continuity in the violence experienced by poor black people at the hands of the police,” she says. “Police brutality is an ongoing story.”

And like in the United States, police officers in South Africa are rarely prosecuted for deaths or other acts of violence. There were more than 42,000 criminal complaints against the police here between 2012 and 2019, according to the Independent Police Investigative Directorate, the country’s police watchdog, including thousands of deaths, rapes, and assault cases. But just 531 resulted in successful criminal convictions, according to an analysis by South African investigative journalism outlet Viewfinder.

“The same across oceans”

For many black South Africans, then, what happened to George Floyd and other black Americans felt like an extension of their own experience.

“The power of these institutions is the same across oceans,” says the organizer of a solidarity vigil for Black Lives Matter in Cape Town last week, who asked to remain anonymous because she is a refugee who worries her activism could threaten her legal status. “We all live in a world where to be black and to be alive is to risk your own life.”

According to court filings by Mr. Khosa’s family, the 40-year-old father was at home with his family the Friday before Easter when soldiers enforcing South Africa’s coronavirus lockdown entered his property, alleging that he had violated the lockdown’s rules by drinking a beer in his yard. (Lockdown regulations prohibited the sale of alcohol, but not drinking at home.) Ms. Montsha and other witnesses have said the soldiers poured beer over his head before choking and beating him.

When the soldiers had gone, Mr. Khosa became increasingly incoherent, vomiting and struggling to speak, according to court papers filed by the family. He lay down, and died three hours later, as they waited for paramedics to arrive.

The South African National Defense Force has denied allegations that soldiers’ actions led to Mr. Khosa’s death. On May 27, its internal investigation cleared the soldiers who allegedly attacked him of responsibility for his death, writing that the “injuries on the body of Mr. Khosa cannot be linked with the cause of death,” and blaming him for “undermining” female soldiers. A police investigation is still underway.

“No one will fill that space,” Ms. Montsha said of Mr. Khosa, speaking to local TV news station eNCA last month.

For his family, he was “the man with the biggest heart in Alexandra,” says Wikus Steyl, the family’s lawyer. (The Khosa family, via Mr. Steyl, declined to comment for this story.) He stretched his own small paycheck to pay for the education expenses of kids in his neighborhood, and had instructed his family to take the lockdown seriously “to keep everyone safe,” Mr. Steyl says.

Harsh lockdown

His death quickly became a symbol for the brutal way South African police officers and soldiers have enforced the country’s coronavirus lockdown. By late May, some 230,000 people had been arrested for lockdown-related offenses. At least 11 South Africans were allegedly killed by police or soldiers in the same period, and another, sex worker Elma Robyn Motsumi, died in police custody, allegedly by suicide, under murky circumstances. To date, no soldier or police officer has been prosecuted. But public outrage is growing, in part because heavy-handed lockdown policing has been directed – albeit in a far less deadly way – at the rich as well as the poor, Dr. Gillespie says.

In mid-May, Mr. Khosa’s family won a court ruling that ordered, among other things, the creation of a simple way for citizens to report allegations of brutality, and of a strict code of conduct for lockdown policing.

But the killing of George Floyd on May 25, and the protests that rippled out from it, further amplified the urgency of finding justice for those killed in South Africa too, says Tumi Moloto. The recent South African graduate of Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts, who uses the pronoun they, says they related to what happened in the U.S. because they have experienced the realities of being policed as a black person in both countries.

“We can and we should be outraged for both the United States and for ourselves,” they say. “It’s not either/or. We can hold both those things in our conscience.”

For many, though, justice still feels a long way off. Mr. Steyl says the Khosa family will challenge the defense forces’ findings in court. Activists, meanwhile, say they hope they can sustain the new attention on the case of Mr. Khosa – as well as the other killings and a series of violent evictions during lockdown.

On Monday, demonstrators led by the Economic Freedom Fighters, a leftist opposition party in South Africa, marched to the U.S. Consulate in Johannesburg, where they sang a traditional anti-apartheid folk song called “Senzeni Na?” or “What Have I Done?”

What have we done?

Our sin is that we are black?

Our sin is the truth.

They are killing us.