Justice without borders: Gambians fight dictator’s impunity from afar

Loading...

| Banjul, Gambia

Deyda Hydara had just turned his blue Mercedes onto a dark dirt road lined with factories when a beat-up yellow taxi with no license plates suddenly appeared behind him, flashing its lights.

It was 10 p.m. on Dec. 16, 2004, and the renowned journalist was driving home from a party at work in Banjul, Gambia’s capital city. He waved out his window for the taxi to pass. But as it pulled around Mr. Hydara’s car, the taxi suddenly slowed. A passenger leaned out the window and fired three shots directly into the Mercedes.

It was easy to guess who ordered the murder of Mr. Hydara, an outspoken critic of Gambia’s dictator, Yahya Jammeh. But the president and his hit squad, the Junglers, seemed all but untouchable, even long after the dictator was ousted from power in 2017.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onFor decades, Gambia’s dictator and his henchmen were untouchable. Now international courts are offering their victims a new path to justice.

Until last November, when a German court sentenced Bai Lowe, the man driving the yellow taxi that night, to life in prison for crimes against humanity for his role in several political murders between 2003 and 2006.

The ruling marked the first time that any member of the Junglers had been convicted for their crimes, anywhere in the world. It was made possible by an increasingly popular legal principle called universal jurisdiction, which allows severe crimes to be tried regardless of where they were committed or the nationality of the perpetrator or victim. In recent years, universal jurisdiction has become an essential avenue to the prosecution of atrocities committed in countries like Syria, where prospects for accountability are otherwise limited.

Now, Gambian activists hope the German ruling will create momentum to help them find justice for many more of Mr. Jammeh’s victims, whether within Gambia’s own legal system or far beyond the tiny west African nation’s borders.

“It reinforces the idea that justice can be served anywhere, no matter who you are,” says Zainab Lowe-Baldeh, an advocate for victims of Mr. Jammeh’s regime and whose brother was killed by the Junglers.

Truth and reconciliation

When Mr. Jammeh fled into exile in 2017 after losing a presidential election, he left behind a nation traumatized by his rule. For 22 years, his regime had employed a range of brutal tactics to stifle dissent, including enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and sexual violence. His targets included activists, political rivals, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and even his own family members.

The new administration of Adama Barrow pledged that justice for these victims and their loved ones was a top priority. In 2018, it established the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) to investigate rights violations during the Jammeh era.

Gambians followed the proceedings with rapt attention – huddling around TVs and radios in restaurants, shared taxis, and corner stores to listen to victims and perpetrators describe the horrors they had been part of. Ayesha Jammeh, a relative of the former president, sat in the front row at the TRRC in 2019 as a Jungler named Omar Jallow described helping strangle her father, Haruna, and aunt, Masie, who were cousins of Mr. Jammeh, in 2005.

For Ms. Jammeh, also an activist for other victims of the former president, it felt like justice might finally be close at hand.

In its final report released in 2021, the TRRC recommended the criminal prosecution of 70 individuals, including Mr. Jammeh and Mr. Jallow. It also urged reparations for victims and comprehensive human rights training for security forces.

But Gambia’s government dragged its feet, citing the COVID-19 pandemic and financial problems. Like other perpetrators, the men who killed Ms. Jammeh’s father and aunt remain free.

A transnational fight

As the TRRC’s calls to action fizzled in Gambia, however, efforts to pursue justice beyond the country’s borders gained momentum.

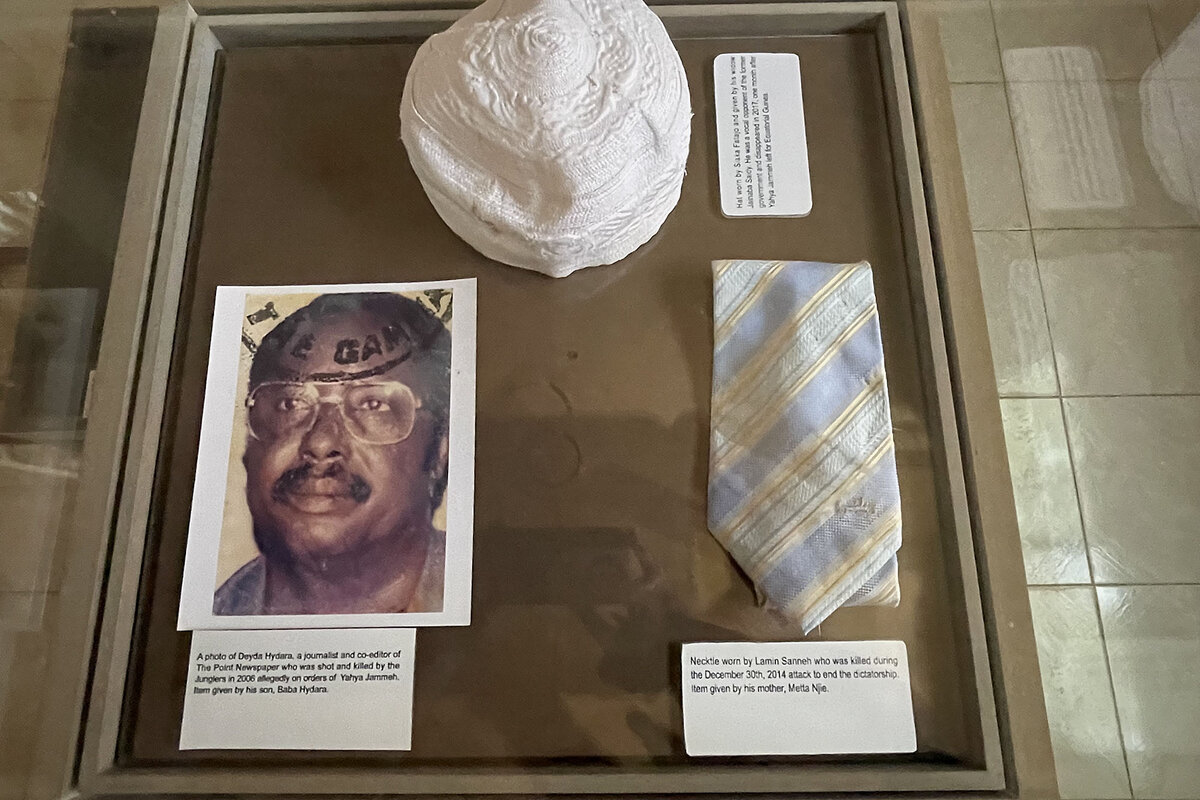

Among those who brought global attention to impunity in Gambia was Baba Hydara, Deyda Hydara’s eldest son. Living in exile after his father’s murder, Mr. Hydara tried to carry on his legacy by working for Reporters Without Borders. After Mr. Jammeh’s ouster, he returned to Gambia to manage Deyda’s incendiary independent newspaper, The Point.

“All over I went to raise awareness about the situation in the Gambia, about what happened to my family,” he says.

But they still lived in the shadow of the murder. Despite evidence pointing to government involvement in Deyda’s death, the family struggled to find concrete answers. The pieces started coming together in 2013, when Mr. Lowe, then living in Germany as a refugee, revealed his role as a driver in the killing in a radio interview. However, it wasn’t until 2021, prompted by additional evidence from the TRRC hearings, that German authorities arrested him.

The subsequent trial spanned 19 months, featuring testimonies from former Junglers, eyewitnesses, and relatives of other victims. Mr. Hydara was a co-plaintiff, and The Point covered the trial extensively, keeping the Gambian public informed about the proceedings.

Although the people who fired the fatal shots at his father remain free, Mr. Hydara sees the verdict against Mr. Lowe as a potential turning point.

“This ... verdict is a big, big relief – not only for the Hydara family but for all the other families of victims in the Gambia,” Mr. Hydara says.

New momentum

Activists say they hope the ruling against Mr. Lowe will snowball into something far larger. Last month, similar proceedings against former Interior Minister Ousman Sonko, an ally of Mr. Jammeh accused of murder, rape, and torture, started in Switzerland. The trial of Michael Correa, another alleged Jungler, is expected to begin in the United States in September.

Critics of universal jurisdiction have argued that the principle is not universal at all – but rather used exclusively by Western courts to pursue perpetrators from less powerful countries.

However, its application has been widely accepted in Gambia’s transitional justice process, and proponents stress that universal jurisdiction trials can be an effective tool to exert pressure on governments to take domestic legal action as well.

“They ... send a strong signal to the Gambian authorities, who are the first concerned, that they should initiate their own prosecutions,” wrote Benoit Meystre, a legal adviser for TRIAL International, which initiated the case against Mr. Sonko, in an email.

In Gambia, Ms. Jammeh, the victims’ rights activist, says she hopes the international cases will be “a wake-up call for our government,” but worries that President Barrow’s commitment to ending impunity is insincere. In 2021, he formed an alliance with a faction of Mr. Jammeh’s party, and he has elevated politicians from that era to senior government positions.

Still, she says, there is reason for hope. There are tentative plans for a new local court backed by the Economic Community of West African States to try Jammeh-era crimes. And last month, a special division opened in Gambia’s High Court that will focus specifically on prosecuting cases referred by the TRRC.

For activists, the hope is that this surge in cases will ultimately arrive at the doorstep of their former dictator himself.

“All these convictions coming mean that Jammeh ... will soon have his turn in court,” Mr. Hydara says.