How Many People Are Surviving on Leaves in the Nuba Mountains?

• A version of this post appeared on the blog "A View From the Cave." The views expressed are the author's own.

To promote his Sunday column, Nick Kristof tweeted the following:

@NickKristof Help spread the word about Sudan starving its people in Nuba Mtains, w/800,000 eating just leaves nyti.ms/L9ayBA

The tweet raises the question: Are 800,000 people eating just leaves* in the Nuba Mountain? Kristof writes:

Ryan Boyette, an American aid worker who stayed behind when foreigners were ordered to evacuate, estimates that 800,000 Nuba have run out of food in South Kordofan, the state encompassing the Nuba Mountains. Boyette has created a local reporting network called Eyes and Ears Nuba, and the Sudanese government showed what it thinks of him when it tried to drop six bombs on his house last month. The notoriously inaccurate bombs missed, and he escaped unhurt in his foxhole.Boyette has done remarkable work by providing on-the-ground reports from the Nuba Mountains. The network that he has created is doing some impressive work documenting the atrocities committed in the region. As far as I can tell, nobody is doing nearly as good of a job as Boyette when it comes to gathering information related to the consequences of the aggression by the Sudanese government.

According to the Sudanese government, just under 1.1 million people live in South Kordofan state, where the Nuba Mountains are located. If Boyette's estimates are correct, that means three quarters of the people living in the region are have run out of food. A Reuters article from mid-May puts the number much lower:

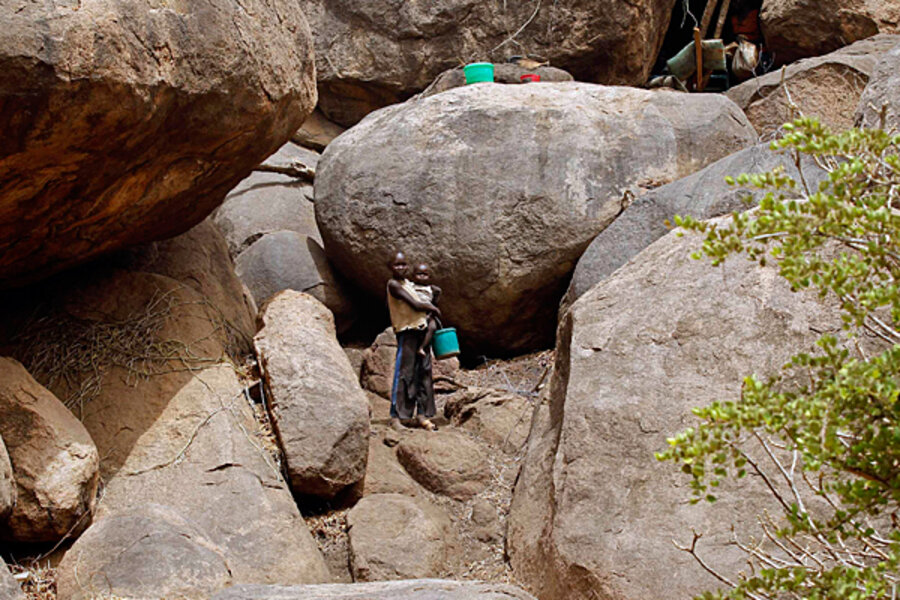

Civil society leaders in the Nuba Mountains, a jigsaw of communities mixing Muslims, Christians and others practising traditional African beliefs, estimate that out of the 350,000 displaced by the fighting as many as 100,000 are hiding in caves, eating tree leaves, sap and wild fruits. They say some are starting to die from hunger.

It seems that 100,000 seems to be a more appropriate estimate which also closely mirrors the 10% severe malnutrition rate that Kristof reports as having been recorded at the Yida refugee camp in South Sudan. The latest estimates from the Famine Early Warning System network estimates food insecurity in the region as follows:

Darfur - 3.0 million

South Kordofan - 200,000 – 250,000 in SPLM-N areas; 150,000 –200,000 in GoS areas

Blue Nile - 100,000 – 150,000 in SPLM-N areas; 100,000 in GoS areas

Red Sea, North Kordofan, White Nile, and Kassala - 1 million

Abyei - 100,000 – 120,000

Total food insecure population - 4.7 million people

See map here:

That is not to say that it isn't a striking story. 100,000 people who are forced to live in caves and gather whatever small food they can find is horrific and deplorable. Roughly 200,000 people facing food insecurity in South Kordofan and 4.7 million people in the region at risk deserves attention.

800,000 appears to be a massive overestimation. That more than doubles the number of people estimated to have been displaced by the conflict. Doing so also neglects the other factors contributing to food insecurity. In addition to conflict, the region had poor harvests over the past year, low food stocks and high prices.

It is worth repeating, what has happened in the region is terrible and must be stopped as soon as possible. However, understanding what is happening to the people in the region is of the utmost importance so the proper humanitarian and international responses can take shape. The difference between 800,000 and 200,000 when it comes to malnutrition is very big and it carries a cost. Furthermore, the fact that conflict is not the only problem means that relief and recovery will require a varied set of interventions.

The Sahel is an example of a stalling yet extremely necessary appeal. Efforts by UNICEF to raise money and awareness about the Sahel show how hard it is to get the right support to provide a proper response. The same applies to the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Horn of Africa and in the Nuba Mountains.

Getting the data as close to correct as possible is crucial, so the request can be extremely targeted, the response can meet the needs on the ground and the expectations of the donors can be met. As much as I hate to admit the last part, it is important. Donors want to see their money put to work in the manner they were told.

Providing the appropriate response to people living in the Nuba Mountains matters most. It is exactly why being precise as possible is so important.

Later this week (I hope), I want to finally take on the question of the power of twitter/social media/slacktavism. There are certain benefits to raising awareness, it is why I strongly believe that DAWNS is necessary, but there are also some serious limitations that should be considered. This seems to be a good example of how easy it is to participate even when the information shared is less certain.

*It has been pointed out by a few people prior to posting this that vegetarians around the world eat only leaves.

Tom Murphy is a former aid worker who blogs about development, aid, and healthcare reform on "A View From the Cave."