Odes to Mexican drug gangs lose their appeal

Loading...

| Mazatlan, Mexico

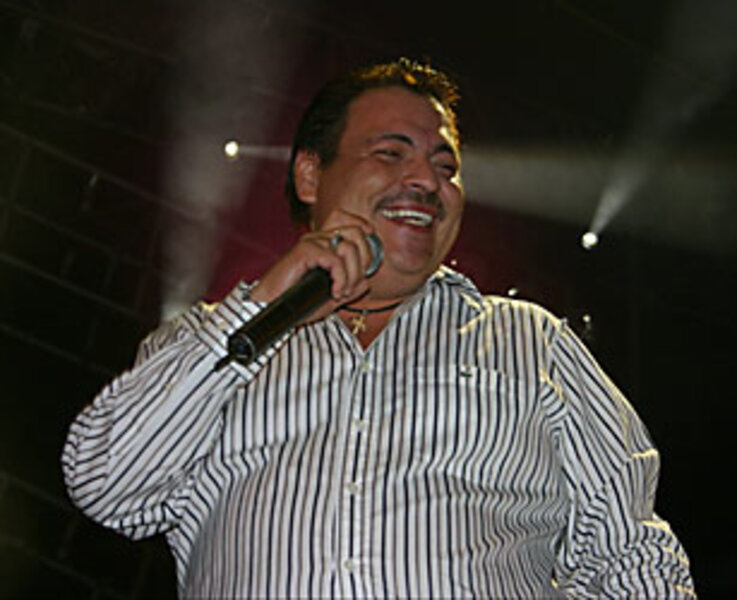

Songwriter Oswaldo Valdez stands with his brass band, "Los Jaibos, on a street corner here, hoping to get hired for a private performance that evening.

The real money, he knows, comes when a drug dealer requests not just a gig but a personal tribute. Mr. Valdez will sit down, listen to the dealer's story, and write him a narcocorrido.

The decades-old genre, which recounts tales of cultivating marijuana in the sierra and escaping gunfire on the streets, has been blamed by many for lauding criminals as heroes, much in the way rap music is often criticized in the US.

Calls for censorship over the years have irked musicians. But that stance is beginning to shift as drug-trade violence has escalated throughout Mexico, in number and brutality, and several narcocorrido artists have been killed as a result.

The recent string of deaths is prompting many, like Valdez, to think twice about composing the lucrative, but potentially life-threatening, lyrics.

"I will work with the low-key guys, but I will not write about murder, because then you, the singer, become a target," says Valdez, who's based in the state Sinaloa, the cradle of Mexico's narco-culture. "And we have to admit, it can generate violence, at least between the drug traffickers."

Murders' chilling effects

Among the musicians killed in the past year, it isn't certain that their lyrics landed them in trouble. One of the best-known singers, Sergio Gomez, who led the group K-Paz de la Sierra, was killed after a concert in the state of Michoacan in December, but was best-known for his romantic ballads. Observers say some musicians may have been victims of domestic disputes or even caught up in drug trafficking themselves.

Still, a trend – real or perceived – has chilled artists.

More than a dozen have been killed in the past two years, and that's only the singers who make the news. In 2006, Valentin Elizalde was killed after his song, "To All My Enemies," became a hit. Jesus Rey David Alfaro, known as "El Gallito," was killed in Tijuana in February.

While corridos have been around since the Mexican Revolution, drug traffickers didn't become the music's heroes until half a century later. Calls for censorship came almost immediately, at least since the release of the 1970s song "Contraband and Betrayal" by Los Tigres del Norte, says Elijah Wald, author of "Narcocorrido: A Journey Into the Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas." In recent years, politicians have called for restrictions and radio bans.

Though musicians generally resisted calls for censorship, some now publicly support more controls. Julio Preciado, one of Mexico's most famous banda singers, used to sing narcocorridos, but at a recent concert in Mazatlan he belted his more famous themes of love and unrequited love.

"I stopped out of respect to my family, he says, in an interview in his tour bus after the concert. "But it's very complicated. It generates a lot of money. I don't criticize those who do it. They are like journalists.... The interpreters aren't at fault."

But even if their work is merely reflective in glorifying the cartels' lawlessness, neither are they contributing to a solution, he says. "It's much more dangerous now. And we have enough violence already."

His concert, which featured five groups – including the Tucanes de Tijuana, one of the most popular narcocorrido bands today – was an homage to producer Marco Abdala, who used to represent Mr. Preciado and was kidnapped and killed three months ago in Mazatlan.

Narcocorridos are usually spun from norteños, a polka-style genre that originated in rural Mexico and is distinguished from other country music by its use of the accordion. But musicians have used all styles, including the brass bandas popular in Sinaloa, to produce narcocorridos.

Where narcocorridos are popular

The music appeals to the poor, especially those from the foothills in Sinaloa, where many major drug lords get their start. "This is what people like here: drugs, mafias," says Bernardo Felix, a resident of the city Culiacan who points to the words of thanks left at the temple.

Narcocorridos are also popular here because drug trafficking is seen as a way out of rural poverty, says Rigoberto Rodriguez, a historian from the Autonomous University of Sinaloa in Culiacan, and the music glamorizes that escape.

Through the 1990s, narcocorridos exploded in popularity, says Mateus Garzon, a concert promoter who helped organize the tribute in Mazatlan. But these days, he says, "I think all of them are going to start to think twice now about singing narcocorridos."

Not all fans will be disappointed. Though Felipe Alcocer says he came to the concert to see the Tucanes de Tijuana, he says that, of all their music, the narcocorridos appeal least to him.

The label narcocorrido is often applied to all songs that deal with drugs, but Prof. Rodriguez says one should distinguish between styles. Some groups do promote illicit activity; others, like Los Tigres del Norte, write about society's ills as a form of social criticism, he says.

Valdez, the songwriter, who also plays the accordian, admits that narcocorridos are tempting. To play at a family party, his band often gets $1,000, he says. A narcocorrido can bring in $4,000. But Valdez says he'd rather be known for ballads. He got uncomfortably close to the violence two months ago when his band was contracted to write a narcocorrido for a party near Culiacan. The event ended abruptly when someone was gunned down a few blocks away.

Such a situation can raise a singer's popularity. "But it's not worth it," Valdez says.