Honduras interim leader may step down. Will that help President Zelaya?

| Tegucigalpa, Honduras and Mexico City

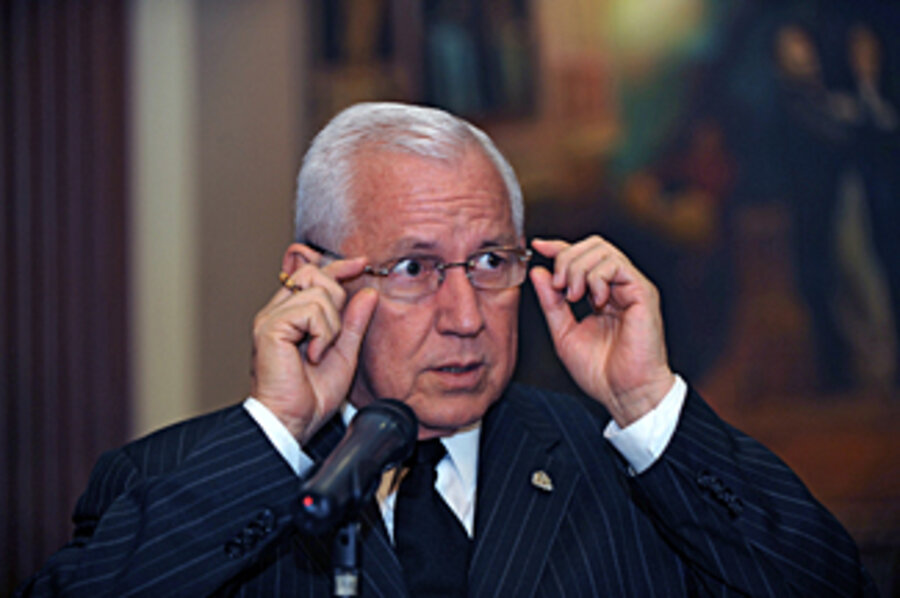

For months, ousted Honduran President Manuel Zelaya – with the backing of the world community – has demanded that Roberto Micheletti step down as the interim president of this Central American nation roiled in political conflict.

Thursday evening, he may have gotten his wish: Mr. Micheletti told the nation that he will likely leave the presidency to allow voters to concentrate on upcoming presidential elections Nov. 29.

But his leave, which would only be temporary, has done little to appease supporters of Mr. Zelaya, nor is it likely to sway the opinion of countries that have said they will refuse to acknowledge election results without Zelaya first in office. (The biggest loser in the Honduras political crisis? Its economy.)

"He says he's stepping down, but he's really just leaving the country without a president for a week," says Rasel Tome, an adviser to Zelaya. "It's a vile trick he's playing on Honduras and the international community. It's a farce. This is still a coup."

On Thursday evening, in a national broadcast, Micheletti said that he could step down from Nov. 25 to Dec. 2, when the Honduran Congress is expected to vote on whether to allow Zelaya to return to office – part of a deal brokered by the US.

"My purpose with this measure is for the attention of all Hondurans to concentrate on the electoral process and not on the political crisis," Micheletti said in a statement, promising to return to office should a national security threat arise. He did not say who, or if another president, will govern in his absence, only that his cabinet will operate "normally."

Zelaya, who has been stuck in the Brazilian Embassy after he snuck back into Honduras Sept. 21, immediately called Micheletti's announcement a ruse. Zelaya was kicked out of the country in June for pushing forward with a nonbinding referendum to explore constitutional change. His critics say he was intending to scrap presidential term limits, forbidden under the current Constitution. He has denied the allegation.

Lawmakers stall on Zelaya vote

Zelaya has said he will not recognize the Nov. 29 elections and has also warned he will not retake the presidency if Congress votes on his restoration after election day, as lawmakers have said they intend to do. Zelaya has called for elections to be postponed.

Under a US-brokered deal, Zelaya had initially agreed to allow Congress to decide his fate, but Honduran lawmakers, who were not bound to a deadline under the agreement, have stalled on making a decision. Zelaya has since pulled out of the agreement.

Some on the streets of Tegucigalpa support Micheletti's decision. "I don't support Micheletti or Zelaya, but I think Micheletti is acting in the best interests of our country," says Edgar Coella, standing with friends outside a downtown hotel. "[It] shows he's not interested in power. What he wants is peace."

Juan Santos, a resident of Tegucigalpa, says he hopes that Micheletti's move will encourage the international community to recognize elections and heal divides between those who support and oppose events in Honduras. "[Micheletti] just didn't want any more problems," he says.

Yet Micheletti's decision will probably sway public opinion. The US has said it plans to recognize the Nov. 29 vote since both sides agreed to the terms of the deal, but countries such as Argentina and Brazil have promised they will not.

"It might give a fig leaf for certain countries already so inclined to recognize the election," says Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Council of the Americas, a consultancy based in New York. "But otherwise I'm not sure it'll have a dramatic impact, because the key question has always been Zelaya's status, not Micheletti's. So long as the Congress won't vote on his return until after the election, the step by Micheletti is more for PR than a serious way to move the discussions forward."