Rio floods: Why did more than 100 people die?

| Rio de Janeiro

As the torrential rains began to cede over Rio de Janeiro today, following the state’s worst floods since 1966, one question was stamped onto every newspaper front-page in Brazil: Why?

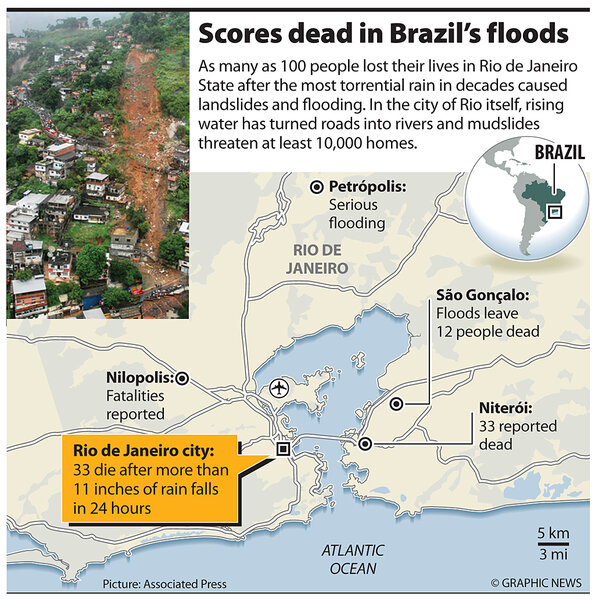

Why was Rio de Janeiro – Brazil’s second largest city and one with a history of tropical rainstorms and flooding – not better prepared for the catastrophe that struck on late Monday and Tuesday this week, when an estimated 11 inches of rain crashed down onto the iconic city and and its neighboring towns in just 24 hours?

With rescue attempts continuing in several of Rio's hillside slums, the city’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, tried to duck questions about why the floods, which have officially claimed at least 105 lives and which brought much of the city to a standstill on Monday night and Tuesday, caused such havoc.

“At the moment, our concern is less about finding out who is guilty, who didn’t foresee this enormous amount of rain, or what was not done,” Mr. Paes told reporters on Tuesday.

But urban planning specialists and environmentalists have been quick to react – blaming Rio’s politicians for decades of poor spending, confused housing policy, and even outright corruption.

“This was an tragedy foretold,” says Sergio Ricardo, a leading Rio environmentalist. “To this day, the city does not have any kind of alert or prevention system – something that is common in other cities that are as vulnerable as Rio.”

Shaky houses on the hillsides

Part of the explanation for the high death toll lies in the way in which Rio’s 1,000 or so favelas have swelled since the 1950s and in how rich and poor alike have been allowed to build houses when, where, and how they pleased – often on steep, water-logged hillsides which are prone to landslides.

“We have an enormous housing deficit so many, many people have been forced to live in at risk areas,” says Mr. Ricardo, who claimed previous governments had misspent or redirected Federal funds intended to help prevent such disasters.

But outside the favelas, the 2016 Olympic city faces a multitude of other infrastructure issues, including a public transport system that is stretched to breaking point and an antique, poorly maintained sewage system.

The Maracana stadium, set to host soccer's World Cup final in 2014 and the opening and closing Olympic ceremonies in 2016, is located in Rio’s north zone at the heart of one of the areas worst affected by the floods, where passengers had to be plucked from city buses by fireman onboard small rubbery dingies.

One Rio newspaper claimed the city had never before witnessed an all-night traffic-jam, stretching through the city center and out toward the north zone.

Old sewage networks

“The sewage and drainage systems are old and undersized,” says Ricardo. “Some sewage networks in the city center date back to the [Portuguese] Empire when the city was inhabited by thousands not millions of people. The network simply cannot cope with these volumes of water and sewage.”

“Coming from Holland, I thought I knew rain but here they are just not ready for it,” says Andreas Urhahn, a Dutch artist working on a social-project painting Rio’s favelas. “The moment the sewer fills up, everything just flows out. Even the cockroaches were in panic – they tried to run up our legs to get away from the floods.”

Ricardo warns that if urgent preventative measures were not taken such floods would continue to take a high toll on Rio.

“At the moment we simply don’t have a plan. But climate change will intensify such events so we urgently need a plan, and one that is actually implemented.”

Brazil’s president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva meanwhile said Rio’s residents should pray for the rains to ease.

“When the Man upstairs is cross and makes it rain all we can do is ask Him to stop the rain so we can get on with our lives,” he said Tuesday.