As deportees return home, Mexico City warms up its welcome

Loading...

| Mexico City

On a recent Tuesday morning, scores of passengers disembarked from an unmarked plane and entered a back corner of Mexico City’s international airport through frosted glass doors.

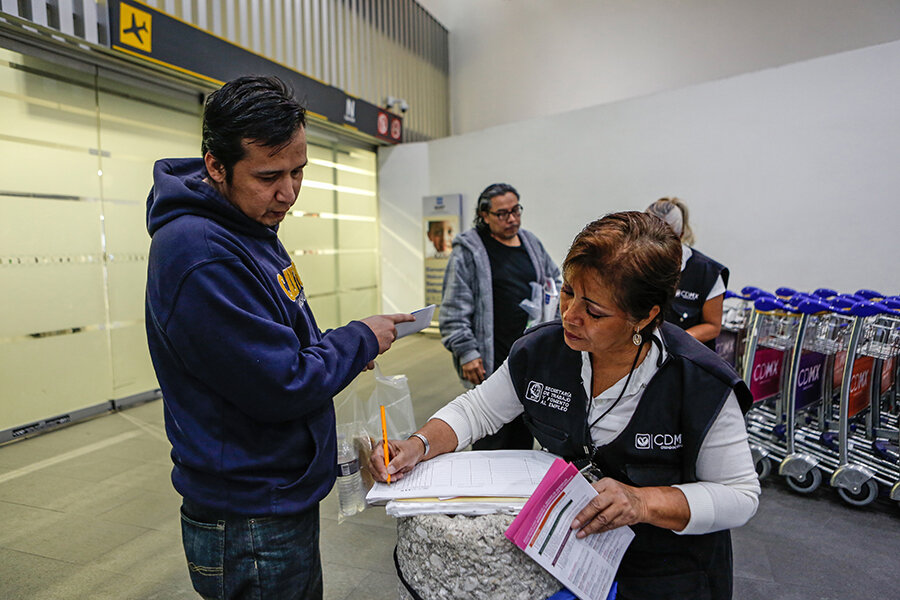

There were no taxi drivers holding up placards with passenger names or loved ones grasping balloons or flowers to welcome them home, just two city employees. The women, whose big smiles contrast with many passengers’ tears, hawked fliers detailing financial support and job-training opportunities in the capital.

Since January, airplanes carrying between 130 and 135 Mexican deportees from the United States have arrived here three times a week. It’s an increase over the two flights a week that arrived starting in 2013, under former President Barack Obama, who some nicknamed “Deporter in Chief” for the record number of deportations that took place under his administration. Deportations from the US to Mexico fell during the first few months of President Trump's term, compared to 2016. Given his promise of a border wall and his aggressive stance on immigrants and deportations, however, many here are girding for an uptick in repatriated citizens.

Mexico’s federal government has long been criticized for its lack of support for deportees, who either fly to the capital, often with their hands and feet bound, or are bused across the border into Mexico by the thousands each month. Many deportees experience discrimination once back in Mexico, where deportation has long been equated with violence or crimes committed in the United States.

But, in March, the government announced an agreement with a private organization called ASUME to provide as many as 50,000 jobs to repatriated Mexicans. It has also taken steps to make it easier to enroll American-born children in Mexican schools or for deportees to access public health insurance. In January, Mexico City’s local government declared the capital a “sanctuary city” for those deported from the US. The city employees awaiting the deportees this day are there to share information about support programs, which provide about $120 per month for up to six months, for those who choose to stay in Mexico City to look for work or undergo job training.

'Everyone lives deportation differently'

Tucked between luggage carts and a silver trash can, city labor department employee Celia Anaya says she’s proud to be one of the first faces deportees see upon their arrival. “If they let me, I give them a hug,” says Ms. Anaya.

She approaches a young man whose eyes are glued to the ground as he enters the airport terminal. José Miguel was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement in early February when he was out buying groceries near his home in Phoenix. He’d been in the US for two-and-a-half months and was working in construction.

“My family doesn’t even know I’m back,” he says. “I left for the American Dream, but it doesn’t exist.”

Ms. Anaya tells José Miguel about his options if he stays in Mexico City.

“There are opportunities here,” she says, adding that deportees often return home with marketable skills, like English proficiency. “If we work together, if we help [those] repatriated to Mexico, we can move our country ahead.”

Today, an estimated 5.5 million undocumented Mexicans live in the US. For some, deportation means the separation of families or the loss of remittances key to supporting loved ones in Mexico. And amid today’s charged environment for migrants in the US, deportation can sometimes even serve as a small relief from families’ constant worry over undocumented migrants’ safety.

“I’m heartbroken,” says María García Morán, one of the few women on this day’s flight. She was taken into custody in the Bronx, just days after arriving to live with her aunt and uncle. She had hoped to get a job cleaning homes and send money back to her family in southern Mexico, but now says there’s no way she’d consider going back to the US: The journey is too risky. “My family is sad, too,” she says. “But they’re also a little happy. I’m safe. I’m back and I’m alive.”

Alma Hernández, who sells tickets for taxi rides from the airport, sits in a kiosk several yards away, watching. She says she’s seen men and women kicked out of the US arriving here for years. But she has felt a new sympathy for those exiting the airport doors in recent weeks.

“The situation in the US right now is so ugly,” she says. Ms. Hernández lived in the US for eight years herself, where she was married to a US citizen. Her children still live there. “If these [deportees] were as bad as [Trump] says they are, they wouldn’t be walking out these doors” without handcuffs or police escorts. “It’s ugly watching this. We are all human,” she says.

Despite the offers for support, not everyone arriving on today’s flight plans to stick around. Mario Martínez had been living in Denver for five years before he was deported.

“I tried my luck in the United States,” he says, carrying an orange mesh bag filled with his few belongings. “It’s a good country that’s now dealing with a difficult president.”

During the first few weeks of Trump's administration he “felt more hunted” in the US, he adds. But he’s not upset. “Everyone lives deportation differently,” he says, nodding toward an older gentleman who is wiping away tears with open palms.

“I won’t go back,” Mr. Martínez says. “But I won’t stay in Mexico.”

He pauses. “I’m thinking about Canada.”