‘Snow moles’ on patrol: Volunteers prowl city’s winter walkways

Loading...

| Ottawa

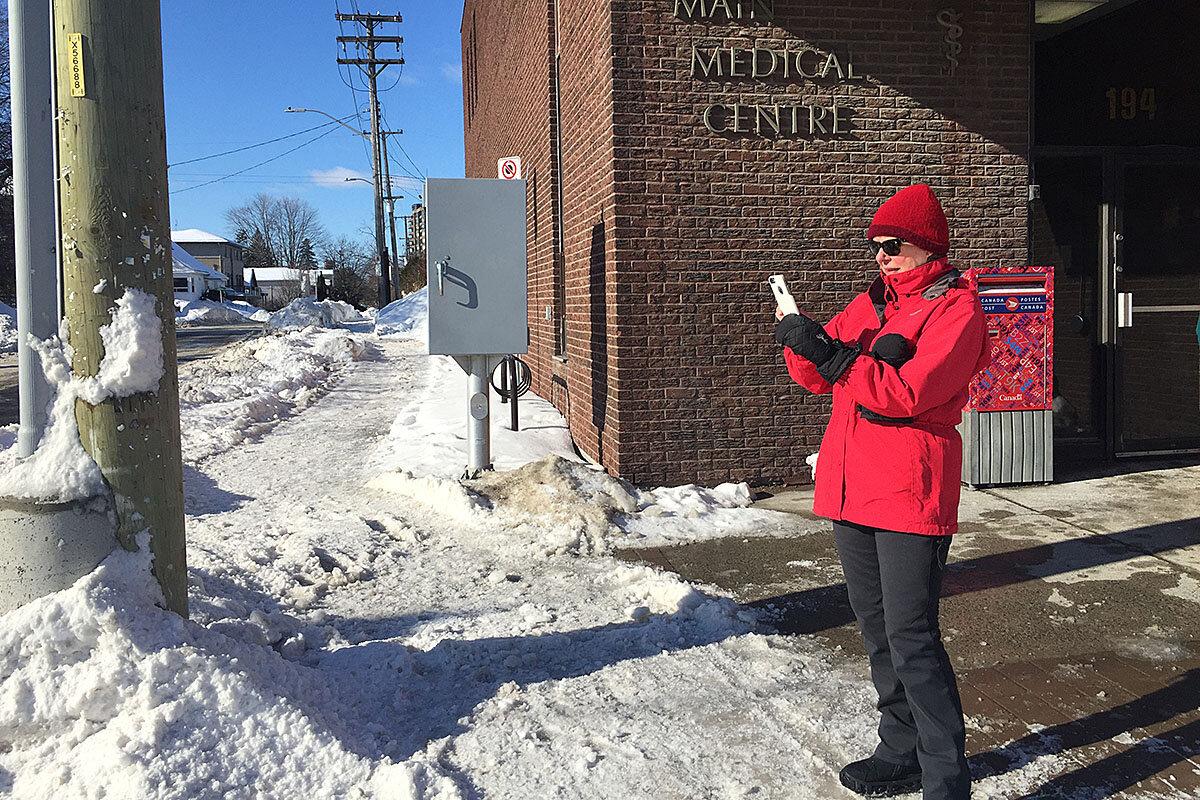

The “snow moles” are a group of mostly senior volunteers in Canada’s capital who are conducting audits – and adding a new perspective – to challenges that winter unleashes onto city streets. The volunteers make sure that bus stops aren’t obstructed by snow banks and that curbs are cleared for passage. A stubborn, uneven sheet of ice covers an entire sidewalk, and Dianne Breton takes a snapshot; later she’ll record her findings online.

The Council on Aging of Ottawa sees their project as a boost to municipal services, not as a blame game. “We’ve had a pretty wicked winter this year,” says Bonnie Schroeder. “City staff have told us we couldn’t pay for this kind of intelligence … about what works, what doesn’t, about what people are saying about their neighborhoods.”

Their data help the city to update its maintenance standards to better reflect a changing climate, with its fluctuations in temperatures and varying snow and rain. And as they gather information, the volunteers get out and stay active – which helps counter the social isolation that can be heightened in winter.

Why We Wrote This

Walkability is increasingly valued, even as a changing climate gives Ottawa a thaw-freeze winter that encourages ice. A Council on Aging program is getting volunteers to pinpoint hazardous trouble spots.

It is Saturday morning, and two “snow moles” are headed to the local post office and pharmacy. Their task: Collect evidence of ice patches, snow mounds, and other wintry conditions that make what should be simple, and often imperative, errands impossible for seniors like themselves.

Skies are blue and the temperature moderate, at least for Ottawa in February. But as soon as Dianne Breton and Ann Goldsmith walk out of their driveways in Old Ottawa East, the snowbanks at hip line, challenges are detected. The sidewalks haven’t been plowed, three days after a blizzard left about a foot of snow. So they make a note of it and are forced to join other walkers, including parents pushing strollers, on the street.

“It’s icy here,” says Ms. Breton, who had a fall a few years ago. Ms. Goldsmith, who fell just the week before, wonders if they should have brought their walking poles. They continue toward Main Street.

Why We Wrote This

Walkability is increasingly valued, even as a changing climate gives Ottawa a thaw-freeze winter that encourages ice. A Council on Aging program is getting volunteers to pinpoint hazardous trouble spots.

The “snow moles” are mostly senior volunteers in Canada’s capital who are conducting audits – and adding a new perspective – to challenges that winter unleashes onto city streets. The volunteers plan to use their data to persuade the city to update its current winter maintenance standards to better reflect a changing climate that has meant fluctuations in temperatures, with varying snow and rain that essentially creates a season of ice. And as they gather their data, the volunteers get out and stay active – which helps counter the social isolation that can be heightened when winter arrives.

“It’s been a really challenging year. We have had everything thrown at us. Huge amounts of snow. We’ve had this freeze-thaw cycle that seems to be happening a lot more than it did even 10 years ago,” says Breton, who chairs the age-friendly pedestrian safety and walkability committee at The Council on Aging of Ottawa. “Winter is a different season than it used to be.”

Freedom – without driving

The car has dominated transport policy since the 1950s, but walkability has shot up priority lists in recent years – raising property values and luring homeowners, says Dan Burden, the director of inspiration and innovation at Blue Zones, an organization focused on increasing community wellness and longevity. Seniors are just as interested in the freedom of moving without cars as young people – even in “winter country,” he says.

Maria Wardoku, a transport planner and board president of Our Streets Minneapolis, says that too often cities still prioritize the car over the pedestrian. Looking out her window after a snowstorm, she says she sees pavement but not the sidewalks, and the high-schoolers on their way to school have to share the roadway with cars. Her group has launched a “Make Winter Walkable” campaign in the past year that includes priority for curb clearing and support for those who can’t get out and shovel themselves.

“It is simply unacceptable that in 2019 we still haven’t figured out how to provide a safe and dignified transportation network for people who are walking,” she says. “It’s about basic access and ability of people to participate in the community, to be able to get to work or to the grocery store.”

Cities and towns have flirted with heated sidewalks, with technology that keeps snow plowed off roadways from then getting dumped onto sidewalks, and with removal procedures that operate like clockwork after a blizzard. But from the more than 100 audits he has led across North America, Mr. Burden says having seniors on the front lines makes a difference to policy.

“Most people who make decisions are younger,” he says. “They have never experienced what it’s like for an elder, or they lack the empathy.”

The city of Ottawa is responsible for clearing sidewalks after a storm ends – unlike many cities like Minneapolis where it’s the responsibility of the property owner – with different standards depending on whether it’s the downtown core or a residential community. It’s a formidable job: There are 3,700 miles of roadway and 1,400 miles of sidewalk in Ottawa that rely on 585 snow removal vehicles.

Extra sets of eyes

The Council on Aging of Ottawa says they see their project as a boost to municipal services, not as a blame game. “We’ve had a pretty wicked winter this year,” says Bonnie Schroeder, program director at the council’s Age-Friendly Ottawa. “City staff have told us we couldn’t pay for this kind of intelligence … about what works, what doesn’t, about what people are saying about their neighborhoods.”

On this day, neighbors have plenty to say. After they greet one another on the street, talk quickly turns to ice. “This is all anyone talks about,” says Goldsmith. “This and the commute.”

Moving carefully, the two women peruse their streets, making sure that bus stops aren’t obstructed by snow banks and that curbs are cleared for passage. For most of the route they are satisfied with conditions. Other audits have reported falls, including of many seniors, and streets impossible for those with mobility devices to cross.

But as they near their destination, a stubborn, uneven sheet of ice covers the entire sidewalk, a barrier to all the services on Main Street. Breton pulls out her phone and takes a snapshot. Later she fills out a survey that will be processed in a database to help uncover trouble spots that they’ll share with the city council. “Doing winter maintenance is a challenging business,” says Bryden Denyes, area manager of road services with the Public Works and Environmental Services Department at the City of Ottawa. ”It’s valuable information for city councilors ... to hear what the community sees and is looking at and experiencing.”

“We’re not going to solve all the problems of winter, but we have to look at them in a different way,” Breton says. She says if streets are safer for seniors, everyone benefits. “We are all on the same side, we want better winter walking.”