How does Barbie fit in Day of the Dead celebrations?

Loading...

| Mexico City

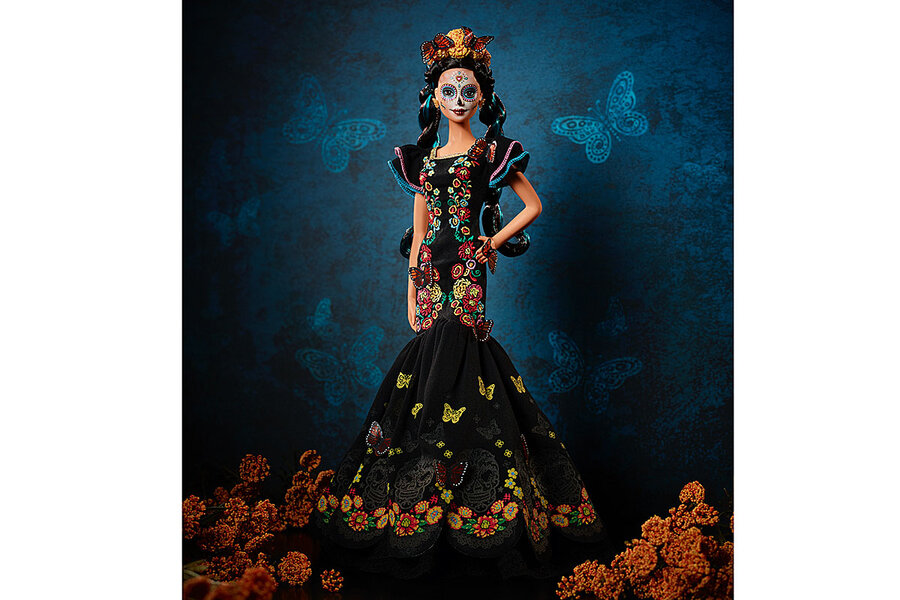

A $75 Barbie is creating waves in Mexican communities on both sides of the border. The Dia De Muertos Barbie, whose face is painted in a skull mask and who wears a black embroidered dress and golden marigold crown, is currently sold out on Mattel’s website and lit up Twitter ahead of the holiday, celebrated Nov. 1- 2 in Mexico. Some people like its simple beauty and that it pays homage to one of Mexico’s profoundest cultural traditions. Others claim cultural appropriation at its worst – corporate America profiting from a spiritual expression that traces back to pre-Hispanic times.

The battle over who owns art, music, fashion, or storytelling has been amplified by social media, where “sharing” is easier, “borrowing” is more visible, and general awareness has grown. “There is certainly in some cases that fine line between appropriation and inspiration,” says George Nicholas, an archaeology professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

Mexico City archaeologist Martin Robles Luengas has no problem with the doll, especially as a countermessage to the criminality and corruption that dominate most news reports about Mexico. “Thanks to these artists, and to these movies, and to this doll, people across the world know the beautiful traditions of Mexico.”

Why We Wrote This

Who owns culture? A new Barbie revives the debate about where the line should be drawn between cultural appreciation and appropriation – and offers lessons in getting it right.

Luis Manuel Piña has been stamping, punching, and pounding sheets of tin into decorative art, a craft called hojalata, for 40 years, since he was 6.

Among his bestsellers this time of year are the catrinas, or female skeleton figurines that symbolize Mexico’s Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead). He creates them in metal or sells them in wood, dressed in bright, elegant gowns and equally bright hats.

So if anyone should have an opinion on American toy company Mattel’s Dia De Muertos Barbie, whose face is painted in a skull mask and who wears a black embroidered dress and golden marigold crown, it is he, a craftsman whose livelihood depends on the customs passed down in his family.

Why We Wrote This

Who owns culture? A new Barbie revives the debate about where the line should be drawn between cultural appreciation and appropriation – and offers lessons in getting it right.

The $75 doll, currently sold out on Mattel’s website, lit up Twitter ahead of the holiday, celebrated Nov. 1- 2 in Mexico, and also on Oct. 31 in the U.S. Some people like its simple beauty and that it pays homage to one of Mexico’s profoundest cultural traditions. Others claim cultural appropriation at its worst – corporate America profiting from a spiritual expression that traces back to pre-Hispanic times.

As for Mr. Piña, his view falls somewhere in between: He feels pride for the interest in a holiday that he says is the most important on the calendar for most Mexicans, but he also voices some regret. “It’s nice that the world has turned its attention on Mexican culture, but I wish it had been a Mexican company that put the doll on sale. It’s, after all, our national object,” says Mr. Piña, whose store is in Mexico City’s main folk art market, the Ciudadela, and is fittingly named The Roots of Mexican Culture.

The battle over who owns art, music, fashion, or storytelling has been amplified by social media, where “sharing” is easier, “borrowing” is more visible, and general awareness has grown. George Nicholas, an archaeology professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, often helps artists who want to know if their work is considered appropriation. His definition entails damage – such as using imagery from indigenous groups that is spiritually inappropriate or watering down a cultural icon or rendering it less valuable. Sometimes charges of it are mistaken.

“There is certainly in some cases that fine line between appropriation and inspiration,” he says. “We respond to what we observe around us. It becomes part of our understanding of the world or part of that landscape that we navigate. And so sometimes we consciously or otherwise incorporate aspects of other people’s heritage into what we are doing.”

Day of the Dead has captured imaginations in recent years, with skulls and skeletons emblazoned on T-shirts and handbags or made into charms hanging off children’s necklaces – not to mention the 2017 Disney-Pixar movie “Coco,” about a Mexican boy determined to become a musician. Sometimes the tradition is capitalized upon with little regard for its origins. In 2017, streaming service Netflix irked many critics by erecting altars to deceased characters from its shows.

Mattel has said its purpose was to help educate people about Mexican tradition. “As a Mexican-American designer, I created Barbie Dia De Muertos to honor, celebrate, and pay respect to the traditions I grew up with and encourage people to celebrate who they are, their loved ones and their culture,” Javier Meabe, a lead product designer for Barbie, says in an emailed statement.

Back in the Ciudadela, Arturo Hernández Jiménez, a guitar maker, says American corporate interest in Día de Muertos doesn’t bother him. When “Coco” was released, a children’s guitar with “Coco” painted on it that he fabricated was all the rage, at least for a few months. “It was a good message about the beauty of our culture, and it’s the same message that the catrina Barbie brings,” he says. “We all learn culture from each other.”

Some fear that a crusade against cultural appropriation could stamp out inspiration that artists have long drawn from others. The catrina itself is borrowed from Jose Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican lithographer. He etched “La Calavera Catrina,” a skeleton in an ornate, aristocratic hat, as a piece of satire in revolutionary Mexico in the early 1900s. Drawing on the relationship with death in Aztec culture, the sketch was a critique of those Mexicans who were denying their indigenous roots and wishing to be European.

Catrinas became popularized, and depoliticized, as a symbol of Mexican culture inside the country. Today they are a part of Day of the Dead celebrations, where families honor deceased relatives by setting up ofrendas, or altars, of their favorite foods and decorating gravestones with elaborate flower arrangements.

The catrina became known to the outside world, says Mexico City archaeologist Martin Robles Luengas, with Diego Rivera’s 1947 mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park,” which depicts a full-scale skeleton alongside famous Mexican figures like Posada and Frida Kahlo. Then came movies and Halloween costumes. Now there is a Barbie.

Mr. Robles Luengas has no problem with it, especially as a countermessage to the criminality and corruption that dominate most news reports about Mexico. “Thanks to these artists, and to these movies, and to this doll, people across the world know the beautiful traditions of Mexico.”