Human smuggling is on the rise. International collaboration is key to halting it.

Loading...

| Guatemala City

The tragedy caught the world’s attention back in June 2022, when some 53 migrants perished inside a tractor trailer, deserted by human smugglers on the outskirts of San Antonio, Texas. More than two years later, seven Guatemalan men were arrested and charged with trafficking. One of them faces an extradition request from the United States for his alleged role as mastermind of the multinational human trafficking scheme.

Despite ongoing efforts by the U.S., Mexico, and other governments in the region to crack down on illegal migration through strict border policies and policing, human smugglers are adept at shifting their “services” to meet the migratory landscape. Some experts see these most recent arrests in the San Antonio case as a positive sign, as it involved international cooperation in the face of a shared challenge.

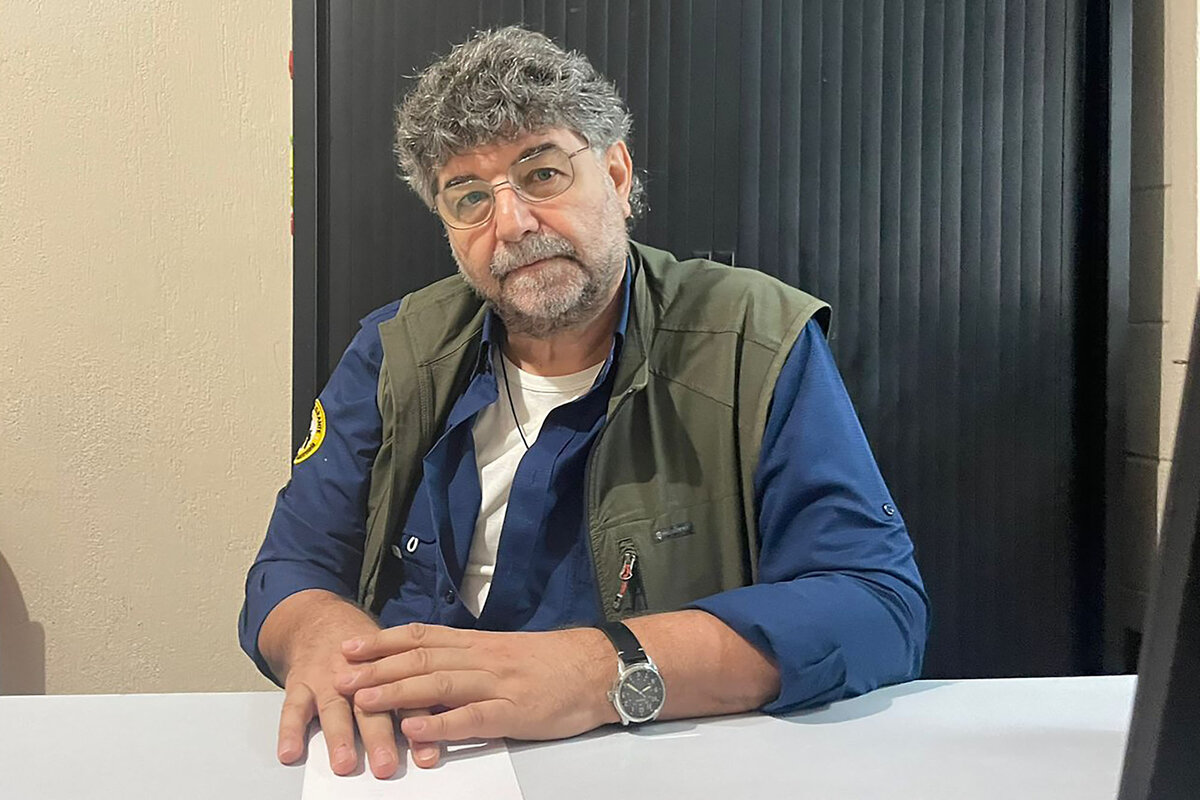

If there isn’t multinational collaboration, targeting both root causes of migration and the people profiting from it, tragedies like the San Antonio case won’t stop, says Francisco Pellizzari, director of Casa del Migrante Scalabrini, a Catholic organization that runs migrant shelters in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico. “It is a global phenomenon, but it can be alleviated through the coordination of governments,” he says.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDespite efforts to crack down on immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border, human smugglers adapt quickly to new laws and regulations in how they market their “services” to desperate migrants. Could indicting traffickers in Guatemala put a dent in their business model?

More than two years since the deadliest human smuggling event in recent U.S. history, fresh arrests in Guatemala signal a new era of cross-border cooperation that experts say is key to stemming smuggling at a time of record-high migration.

Seven men were detained by the Guatemalan government late last month and charged with trafficking in the 2022 deaths of 53 migrants who perished in a tractor trailer abandoned in the sweltering Texas heat by a network paid to safely – and illegally – bring them into the United States.

U.S. authorities have put in an extradition request for one of the men. He is believed to be the mastermind of the operation, which killed several children, a pregnant woman, and dozens of other Guatemalan, Honduran, Mexican, and Salvadoran immigrants seeking safety and opportunity in the U.S.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDespite efforts to crack down on immigration at the U.S.-Mexico border, human smugglers adapt quickly to new laws and regulations in how they market their “services” to desperate migrants. Could indicting traffickers in Guatemala put a dent in their business model?

As migration grows – and immigration laws become more restrictive – the trafficking of migrants desperate to reach the U.S. has flourished. Human smugglers often oversell their “services,” offering anything from safe passage to supposedly processing asylum requests, targeting a vulnerable and desperate population at a high cost. Although the August arrests in Guatemala may seem like a drop in the bucket at a time when, globally, human migration is at a historic high, observers say it’s a step in the right direction. The twelve people, including two U.S. citizens, now facing charges for the tragic end of these migrants involve those at all levels of planning, from mapping out the route to recruiting “clients,” to driving the big rig that was eventually abandoned.

If there isn’t multinational collaboration, targeting both root causes of migration and the people profiting from it, these tragedies won’t stop, says Francisco Pellizzari, director of Casa del Migrante Scalabrini, a Catholic organization that runs migrant shelters in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico. “It is a global phenomenon, but it can be alleviated through the coordination of governments,” he says. “It has to be a response from various operators, actors, governments, and civil society.”

“A collaborative effort”

Deisy Fermina López Ramírez first left home when she was 15 years old, and, like many migrants, first looked for answers to her family’s poverty inside her home country. She moved 155 miles away to Guatemala City, where she held different odd jobs, earning roughly $150 per month. But it wasn’t enough to put food on the table and support her family, says her father, Oslidio López, an Indigenous farmer in a lush, mountainous village in northwestern Guatemala.

When Ms. López was 23 years old, she contacted a group of human traffickers, referred to locally as “coyotes” or “polleros,” whom she paid for safe passage from Comitancillo, San Marcos to the U.S. with the deeds to the land where her family lives. Her parents also took out a loan to help pay the fee. Her father declined to say if they are still paying interest on the loan.

Weeks after her departure for the U.S., her family’s world shattered with the news that Ms. López was one of the 53 people who were left to perish in a sealed big rig, without access to water or fresh air, in the brutal Texas heat.

“One feels bitterness and pain, but I cannot do anything, as much as I would like to,” says Mr. López, who adds that he doesn’t understand the legal system here, and that the arrests have done little to dull the pain of losing his daughter.

Guatemala’s Public Ministry reports that between 2022 and 2024, some 230 people accused of trafficking migrants were arrested here. But, without international cooperation, arrests like these may not result in much, especially in a country where collaborations between criminal groups and local police are common place, says Carlos Eduardo Woltke Martínez, deputy director of the Guatemalan Migration Institute (IGM).

On Aug. 21, Guatemalan officials announced the arrests of seven people accused of helping smuggle some of the migrants who died alongside Ms. López. That included Rigoberto Román Mirando-Orozco, the alleged ringleader. The next day, U.S. authorities announced Mr. Orozco’s indictment and extradition request.

“This is a collaborative effort between the Guatemalan police and [the U.S. Department of] Homeland Security, in addition to other national agencies, to dismantle the structures of human trafficking,” Guatemala’s interior minister told the Associated Press last month.

The shifting “how” of migration

The dynamics of migration have changed dramatically over the past two decades, and that includes how – and with whose guidance – people are migrating, says Cindy Espina, a journalist and investigator of migration based in Mexico City.

“It is no longer the relatives or local leaders, as it was in the 1990s, who guide migrants” north, she says. “Now there are trafficking networks across Mexico that can charge almost $20,000 per trip” to the U.S.

As organized crime and drug trafficking have grown in the region, so too have restrictive immigration policies. Following Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. southern border became more militarized, halting what for generations were circular patterns of migration, with laborers coming to the U.S. seasonally and then returning home. Later came pandemic-era policies that essentially shuttered the U.S. border to outsiders without visas, creating a buildup of desperation among migrants. Most recently, strict asylum restrictions have changed border dynamics once again.

Instead of single, working-age men, today migrant shelters are overwhelmed by previously atypical migrant profiles, like families, unaccompanied minors, and the elderly.

Mr. Pellizzari, from Casa del Migrante, says that in 2023 the organization served around 32,000 people at the shelter in Guatemala City alone. That’s almost double their 2018 record, when a caravan of Honduran migrants passed through the shelter and they assisted roughly 18,000 people.

As organized criminal groups expanded their business models beyond drug trafficking to include kidnapping, extortion, and human smuggling, migratory routes became infiltrated by predators. Human smugglers now commonly advertise their services through local radio stations and social media networks, such as TikTok, says Mr. Woltke.

“People feel like they are beneficiaries of a service,” says Mr. Woltke. “But they are victims of a crime.”

And it’s not just high fees, but increasingly people might pay with deeds to their land, like the López family, or take out sky-high-interest loans from unauthorized agents. This generates long-term costs – and more pressure to arrive in the U.S. one way or another to start earning money – that can create a situation that “worsens the poverty of people who sought to migrate to escape from it,” he says.

According to estimates by the IGM, 90% of migrants who returned to Guatemala in the past five years barely managed to cross more than 60 miles into the U.S. before being deported back to unsustainable debt.

Human smugglers “will always look for a way to make a profit through the people,” says Mr. Woltke. “Their goal is not the safety or the integrity of migrants.”