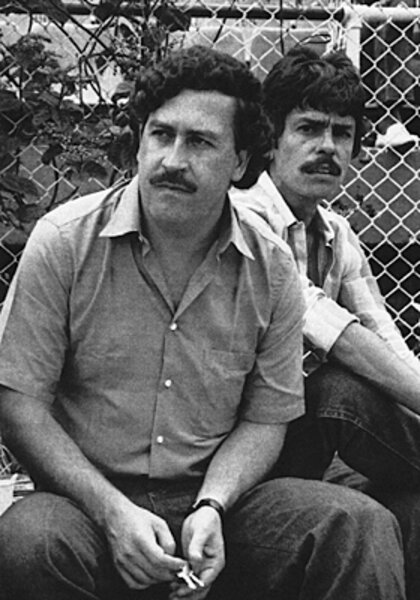

New TV series on druglord Pablo Escobar: Why the continued interest?

Loading...

• Insight Crime researches, analyzes, and investigates organized crime in the Americas. Find all of Elyssa Pachico’s work here.

The latest episode of "Pablo Escobar: The Boss of Evil" airs June 4 on Caracol TV. The debut last week attracted some 11 million viewers, the network said, a number that is expected to climb until the series finale.

One promotional spot for "The Boss of Evil" (see video at original post) is indicative of some of the difficulties that the show's creators face in packaging the program for a Colombian audience. The ad has several segments, each representing a different facet of Escobar's life: ruthless killer, rich businessman, lover, and finally the world's most hunted man. A deep-voiced narrator describes well-known stories about Escobar, such as the fact that he paid assassins 1 million pesos (today worth about $545) for each police officer killed. Each segment ends with the narrator asking the audience, "What do you believe?"

The implication is that the Colombian public – including a new generation not quite old enough to remember Escobar's era – can select the vision of Escobar they most want to believe in. One of Escobar's greatest public relations skills was blurring the line between truth and lies, forcing Colombians to choose between his version of reality and the state's, which had its own serious credibility problems. Escobar's hand-scrawled communiques often lambasted police brutality in the Medellin slums that served as his powerbase. These accusations had some truth to them. But Escobar's depiction of reality was fundamentally warped: he denied his involvement in drug trafficking until the very end, and famously described his 1991 surrender to the government as a "sacrifice for peace." The implication was similar to the question posed by "The Boss of Evil" promos: Did Colombians believe Escobar's presentation of himself as a populist businessman, or the state's picture of him as murderous kingpin?

Related: Think you know Latin America? Take our geography quiz!

An article on Escobar published by Semana news magazine in 1983 (in Spanish) gave one of the most popular visions of Escobar, describing him as a "Robin Hood" who strolled around Medellin neighborhoods, addressed by inhabitants as "Don Pablo." This ambiguity of Escobar's legacy is one reason he continues to fascinate, and why he makes for great TV. Contradictory characters are the most interesting ones. And audiences are drawn to stories of hubris – by the end of Escobar's life his $3 billion fortune was squandered, and he was on the run, unable to stay more than six hours in a single location.

"The Boss of Evil" is not the first time that a Colombian telenovela has mined the world of drug trafficking for material. But by making Escobar the protagonist, the TV show is courting controversy, asking its audience to view him with curiosity and interest. This raises difficult questions over whether such a position borders on complacency towards Escobar's crimes, or approval of his lifestyle. Two of the show's creators had family members who were victims of Escobar's violent campaigns, allowing Caracol TV to avoid accusations that the TV show is painting too sympathetic a portrait of the Colombian drug lord.

Escobar's mystique is also related to his ambiguous position as Colombia's ultimate capitalist. He brought a flush of foreign cash into the country, fueling building booms and propping up businesses. He was an independent innovator and a micro-manager who hated to delegate.

And in his own twisted way, Escobar could make an argument that his cocaine trafficking business was a patriotic effort. Dating back to the 19th century, coca and cocaine were controlled and consumed by Western commercial interests. Unlike other natural resources in South America, Escobar made cocaine a Colombian-run business, bringing in huge profits that actually stayed in the country.

Related: Think you know Latin America? Take our geography quiz!

Escobar was behind other innovations. He used urban terrorism in a way never before seen during Colombia's decades of conflict. He made casual, brutal violence an accepted tactic of the drug trade. His cunning communiques, aimed at manipulating public opinion and justifying the acts of violence he described as "reprisals" against the state, are echoed today in the "narco-banners" hung across Mexico. And as Gabriel Garcia Marquez writes in "News of A Kidnapping," an account of Escobar's campaign to force the government to revoke its extradition laws, Escobar's cultural influence still lingers:

Easy money ... was injected into the national culture. The idea prospered: The law is the greatest obstacle to happiness, it is a waste of time learning how to read and write, you can live a better, more secure life as a criminal than as a law-abiding citizen – this was the social breakdown typical of all undeclared wars.

But as much as Escobar was an innovator, setting the tone for how organized crime continues to do business today, it is impossible to separate him from Colombia's history. Many members of Colombia's traditional land-owning elite could also trace their wealth back to criminal enterprises: contraband smuggling, land seizures, and slavery. Escobar's wealth came from just another industry that was technically illegal. And like Escobar, Colombia's elite long practiced their own system of violent justice, forming private armies to protect their interests in the countryside. By using violence as a tool to achieve his economic interests, Escobar formed part of the same tradition. The Medellin kingpin did not emerge from a vacuum.

The creators of "The Boss of Evil" argue that the TV show is intended as a way to relive one of the most difficult periods of Colombia's past. By emphasizing historical accuracy, the show will not act as a justification of Escobar's actions, the show creators say. As Semana points out (in Spanish), telling stories about bad guys is seductive. The irony is that the TV show is asking is audience to do something that Escobar repeatedly proved he was totally incapable of doing: distinguishing between good and evil.

– Insight Crime researches, analyzes, and investigates organized crime in the Americas. Find all of Elyssa Pachico’s work here.