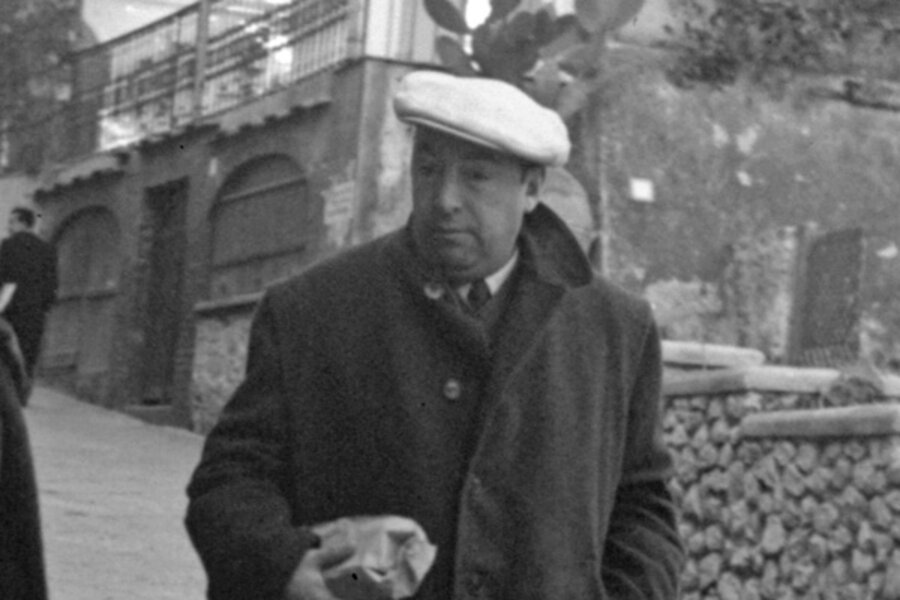

Chile's Pablo Neruda: from Nobel laureate to center of suspected murder plot

Loading...

| Santiago, Chile

When Pablo Neruda died in 1973, the bookish boy from a sleepy town in southern Chile had already played many roles. He was a Nobel laureate in literature. A diplomat to Spain, France, and Burma (today Myanmar). A senator who fled his homeland on horseback when his Communist Party was banned, and later a presidential candidate. A husband to two women, a father to a daughter.

And now, four decades after his death, Mr. Neruda is at the center of a murder mystery. Was he killed in the early days of Chile’s military dictatorship?

Neruda’s widow, Matilde Urrutia, never accepted the consensus story that he died of heart failure as a result of advanced cancer. But she never came forward with the bombshell dropped a couple years ago by his assistant and driver, Manuel Araya: that Neruda had been in decent shape and was planning to fly into exile – until he was injected with an unknown substance on the day he died.

The BBC interviewed Mr. Araya, who said he remembers that day:

Despite the passage of time, Mr. Araya says he remembers clearly what happened in the days after the military coup.

He says Neruda was admitted to hospital on 19 September 1973, and was due to fly to Mexico on 24 September.

"On the morning of 23 September, Matilde and I went back to Isla Negra to collect some of his belongings," he recalls.

"While we were there we received a phone call from Neruda in the clinic.

"He said 'Come back here quickly! While I was sleeping a doctor came in and gave me an injection in the stomach.'"

Mr. Araya says he and Matilde drove back to Santiago immediately. "Neruda died at around 22:30 that evening," he remembers.

Today, the head of Chile’s forensic medical service is leading a team of 13 experts who supervised the weekend exhumation of Neruda's corpse, nearly 40 years after he was laid to rest. The body is now in Santiago, about 75 miles from its resting place in coastal Isla Negra. The doctors aim to find signs of advanced cancer, signs of poison, or any other clue that could help them prove or disprove Araya’s statements.

The project follows the equally high-profile exhumation of President Salvador Allende two years ago. Mr. Allende died during the coup itself on Sept. 11, 1973. There was always some doubt about whether he killed himself or whether he was shot by soldiers taking over the presidential palace in Santiago. The forensic scientists confirmed that the death was a suicide.

General Augusto Pinochet led Chile’s military dictatorship from the day of the coup until a peaceful handover of power in 1990. In the first days of his rule, thousands of leftists were herded into detention centers, tortured, and at times killed. Neruda, despite being the country’s highest-profile communist after Allende, was still free when he checked into the hospital on Sept. 19.

Chileans have long wondered whether Neruda may have suffered a fate similar to that of former President Eduardo Frei Montalva and Allende’s interior minister, Jose Toha. Both died in the hospital, but judges later ruled that both men were murdered – Mr. Toha by strangulation and Mr. Frei by poisoning.

Following Araya’s allegations, Chile’s Communist Party filed a court case in 2011 to request a judicial order for an exhumation.

The mystery has drawn press attention from around the world, with photographers and TV crews jockeying for a view of the exhumation and competing to interview those who knew the poet. The current president of Chile’s Communist Party, Guillermo Teillier, was at Neruda’s beachfront home and burial place for the excavation and removal.

The tests aren't guaranteed to lead to any conclusive results, and thus the truth may never be known about the end of Neruda’s life. For now, the mystery is a cliffhanger. A wait of at least three months is expected before forensic results are released.