Burma's wealth gap breeds discontent

Loading...

| Rangoon, Burma

In a country where electricity is available only a few hours a day and those with a job can barely afford the bus ride to work, Burmese pack the teahouses here and gossip about the decadence of the top brass.

"In Rangoon there is complete neglect, but in Naypyidaw everything is good," Min, a construction worker, tells his friends. He asks that only his first name be used for security reasons. Min is referring to the new capital 250 miles north, to which the top generals and their families have relocated and which cost between $122 million and $244 million to build, according to the International Monetary Fund.

"They are building swimming pools and golf courses and very good roads," Min whispers to the others. "They have better Karaoke clubs too ... with dancing girls!"

The gap between the haves and have-nots in Burma (Myanmar) is growing every day. And it's this poverty and inequality, say observers, that fuels the discontent here – perhaps more than any yearning for democracy.

"If [top leader, General] Than Shwe delivered on the economy," argues Robert Rotberg, director of Harvard's Kennedy School Program on Intrastate Conflict and Conflict Resolution, "[then] everyone would agree to wait for democracy. But the junta robs and strips the economy.... Indeed, the junta systematically loots."

Not that the regime seems eager to deliver political reform, either: Many expect a constitutional referendum set for May 10 to further the junta's control, and do little for individual freedoms.

"The key question is economic," agrees Zin Linn, a Burmese activist and journalist who was jailed for seven years by the junta, and today lives in exile in Thailand. "We are facing starvation because of the junta's policies of mismanagement and selfishness."

Weeks' wages for rice

At independence 60 years ago, Burma was regarded as the Southeast Asian nation "most likely to succeed" based on economic indicators at the time compiled by ALTSEAN, a regional human rights lobby. The country is awash with natural wealth, from extensive oil and gas reserves to world-renowned rubies.

But the country today is aching with poverty. "This country is, how shall I put it, a disaster. A disaster of many decades in the making," half-jokes comedian U Lu Zaw, a member of the famous anti-regime Moustache Brothers comedy troupe in Mandalay.

Within the past five years, the price of cooking oil in Burma has risen tenfold. One sack of the lowest quality rice here costs half of Min's month's wages. The UN estimates that the average household spends more than 70 percent of its income on food. The World Food Program recently announced it would spend $51.7 million over the next three years in food aid for up to 1.6 million vulnerable Burmese.

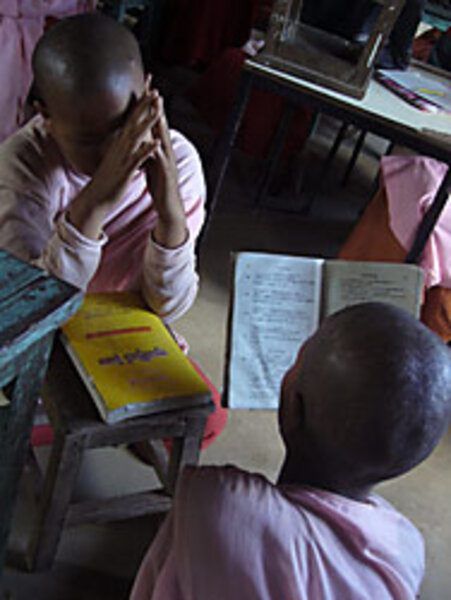

The World Health Organization routinely ranks Burma's overall healthcare system among the worst in the world. Less than half of Burmese children go to primary school, compared with 70 percent of children in Southeast Asia who complete secondary school.

What's happening? To begin with, the regime spends about half of its annual budget on its 400,000-strong military, shelling out billions of dollars for everything from warships from China and tanks from Ukraine to jet planes and a nuclear reactor from Russia. Less that 3 percent of the budget is spent on health services, and just 1 percent on education. Burmese officials blame economic sanctions by the United States and the European Union. But analysts say the rest of the story is one of mismanagement and corruption.

Even the employed here can't afford to buy a 10-cent newspaper on a regular basis: According to the BBC World Service Trust, on average, a single paper is read by 10 adults, meaning people are pooling resources to buy them. Yet when the poor do open the papers, they find society pages filled with displays of extravagance: champagne parties, mansions bought and sold.

Diamonds for the general's daughter

In this environment, rumors breed freely. Few urbanites have not seen bootleg DVD copies of General Shwe's daughter's extravagant wedding. Were all those diamonds real? Was that tiara pure gold? And does Shwe's grandson really take a private plane to Singapore for school every morning?

No one knows, but increasingly people are convinced they are poor because their leadership is stealing from them. "There are two different worlds in Burma, and one comes at the expense of the other," says Min.

Many Burmese today are forced to buy generators or make do with candles. Burma has sufficient energy, but the leadership is selling it abroad. According to a 2007 report by the US Armed Forces' Pacific Command, Burma produced only 1,775 megawatts of power for its 53 million people in 2006 but sold neighboring Thailand 26,000 megawatts for its 63 million people. The monies from those sales have not been accounted for. It's a story that repeats itself in sector after sector.

Bringing this up with the junta leads to stonewalling, or worse, as Charles Petrie, the most recent UN director in Burma, discovered. "In this potentially prosperous country basic human needs are not being met," Mr. Petrie wrote last October. The junta's response? Petrie "has acted ... beyond his capacity by issuing the statement which not only harms [Burma's] reputation but also the reputation of the United Nations," they retorted – and kicked him out of the country within months.