North Korea releases American to Jimmy Carter with a message - and a snub

Loading...

| Seoul, South Korea

Former President Jimmy Carter flew teacher-preacher Aijalon Gomes from North Korea to Boston on Friday after apparently waiting three days for North Korea’s "Dear Leader" Kim Jong-il to honor him with a face-to-face meeting.

Instead, Kim’s second in command, Kim Yong Nam, received Mr. Carter in a ceremony on Wednesday night, after which he and his group spent a full day and one extra night in Pyongyang. The experience was evidently unscripted, and how they spent their time remains a mystery.

“Carter is probably disappointed he did not see Kim Jong-il,” says Han Sung-joo, a former foreign minister and one-time ambassador to the US, “but he did not come back emptyhanded."

TV images show Carter flashing his trademark grin as he bade farewell to his hosts and betraying no sign of the frustration he may have experienced when he learned Thursday morning that Mr. Kim had already left by armored train for Jilin Province in northeastern China.

“That was an intended snub,” says Shim Jae-hoon, a longtime analyst of North Korean affairs for magazines and think tanks.

The Carter Center did betray its disappointment in the wording of a three-sentence announcement of the departure that offered no thanks or appreciation for the reception in Pyongyang or Gomes’s release. The statement simply said that Kim had “granted amnesty” to Gomes “at the request of President Carter, and for humanitarian purposes. “ The statement also noted that Gomes had been imprisoned in January and “sentenced to eight years of hard labor with a fine of about $600,000 for the crime of illegal entry into North Korea.”

There was no indication who paid the fine, or how, but the clear inference was that North Korean authorities had gotten the money before Gomes’s departure. Nor is it yet known who chartered or paid for the jet that carried Carter and his entourage to Pyongyang on Wednesday.

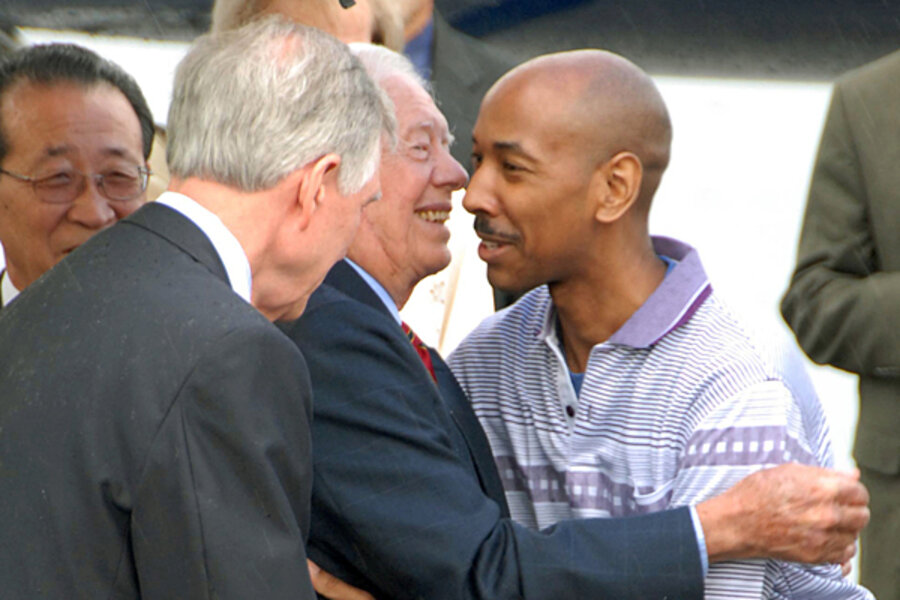

Mr. Gomes, looking fit in a short-sleeved light blue polo shirt, embraced Mr. Carter on the tarmac of Sunan Airport outside Pyongyang before climbing up the stairway onto the private jet that flew him home to Boston and a reunion with his mother and other family members.

Mr. Carter went to Pyongyang hoping to get the same red-carpet treatment as Bill Clinton, who traveled there in August last year to pick up two women who were filming for Al Gore’s Internet TV network when they were seized by North Korean soldiers on the Tumen River border with China. Mr. Clinton and aides spent three hours over a lengthy luncheon with Kim before taking the women back to California on a private jet.

Messages exchanged

“The North Koreans must have been tempted to take advantage of Carter’s visit,” says Lee Chang-choon, a retired ambassador and veteran of negotiations on North Korea’s nuclear program, “but Carter has no influence” – a remark suggesting he's not as likely as Clinton to have a real effect on US policy on Korea.

Still, Carter is returning to the US with a message: North Korea wants to renew six-party talks on its nuclear program that it’s boycotted since December 2008.

Thus Carter appears as a player in a broad diplomatic offensive waged by both North Korea and China, the North’s only real ally, to get beyond recriminations over the sinking of a South Korean navy vessel the Cheonan in March. North Korea has said it wants to reopen talks that might conceivably lead to yet another agreement under which the North would get an enormous infusion of aid in return for a promise to stop developing nuclear warheads.

Mr. Shim doubts, however, if six-party talks, even if they resume, will be all that important. “Nobody’s interested,” he says. Both the US and South Korea, he notes, have made clear they need a sign that North Korea will comply with previous agreements, including two reached in 2007.

In any case, Shim believes Kim Jong-il has higher priorities than talk about talks.

Higher priorities in China?

His visit to China included the possibility of a summit with China’s President Hu Jintao, at which he was widely believed to want to introduce his third son and heir presumptive, Kim Jong-un. The timing in itself appeared as a carefully calculated message of North Korea’s extreme displeasure with US policy as epitomized by strengthening sanctions

Then, says Shim, “he’s asking for massive aid.” North Korea “is flooded in recent rains, and they’re running out of food,” he notes. “Only China will help. China knows North Korea has nowhere else to go.”

At the same time, Carter’s trip to North Korea was met with derision in some quarters here. Kim Bum-soo, publisher of a conservative journal, notes that Carter, when he was president of the US and the late dictator Park Chung-hee was president of South Korea, was a strong critic of human rights abuses in the South.

“But he never criticized North Korea’s human rights record,” says Mr. Kim, quoting the expression, “If you are sympathetic toward the oppressor, you are against the oppressed.”