Japanese stay put for now despite nuclear radiation worries

Loading...

| Sendai, Japan

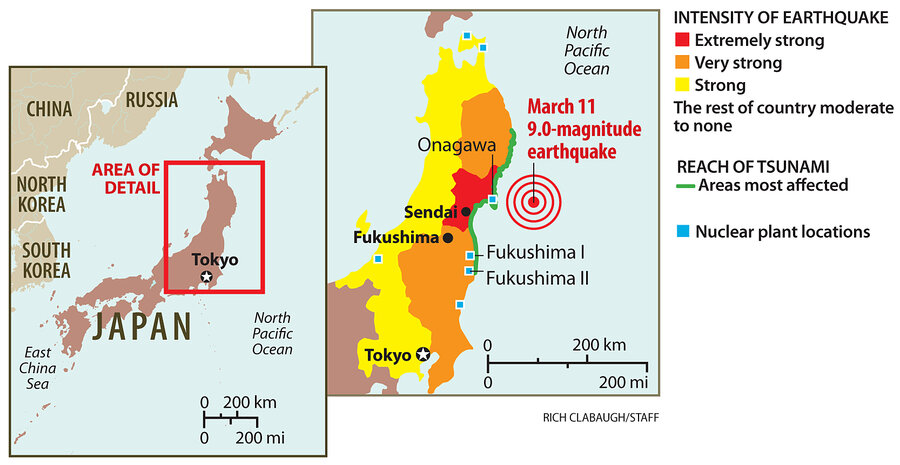

As radioactivity continued to leak from four stricken nuclear reactors at Fukushima, 60 miles south of this port city, fear of the invisible threat is spreading amongst citizens here.

In the absence of any warning from Japan's government for this town, however, and with gasoline almost unobtainable, few appear to be thinking of fleeing their homes.

“Where should I go? What should I do?” asked Chiyoe Kikuchi as she stood by a pile of sacks of rice she was selling. “So many roads are closed and there is no fuel, so it is really difficult to get further away."

Japan nuclear crisis: Nuclear terminology 101

There is no sense of panic in this city of 1 million people, the closest town to the epicenter of last Friday’s magnitude 9.0 earthquake that caused a massive tsunami that tore the port to shreds, but there is deep uncertainty.

“The Americans say one thing and the Japanese government says another” about the real danger of radiation in the area, complained Kazuaki Nohala, a construction worker who was picking up some groceries for friends at a convenience store that had just opened for the first time since the earthquake. “That makes me worried and confused."

US embassy warning

The US Embassy in Tokyo issued a warning late Wednesday night, advising Americans living within 50 miles of the Fukushima nuclear plant to leave the area. The Japanese authorities have evacuated residents from a much smaller area within just 13 miles of the reactors.

The embassy said it had information that warranted “precautionary” evacuation.

Meanwhile, people stocked up on food supplies at the few shops that opened their doors for a few hours, lining up in the snow to wait their turn.

At one 7-11 convenience store, shoppers were limited to two bottles of water each, and three sticky-rice balls wrapped in seaweed. The shelves were empty of rice, bread, canned goods, frozen food, chocolate, and many other items.

“Open today from noon. Store will close when supplies run out,” read a hand-written notice on the door.

At a fruit and vegetable store on the outskirts of the city that had received a delivery earlier that morning, shoppers bought more than they usually do, said the owner, Keiko Shoji, but they did not overfill their baskets.

“I bought what my family will need for the next couple of days,” said Akemi Ito, returning to her car with a bag of pumpkin, potatoes, eggplant, and salad. “You have to think of other people.”

Mrs. Ito will cook them on a stove she has hooked up to a gas canister, since the town gas supply is cut. Her water is out as well; her mother-in-law collects snow to melt in order to flush the toilet, but she said she is careful not to touch it with her hands.

“We’ve heard on the Internet that snow and rain can be radioactive,” she explained.

Long lines, dwindling supplies

Ryoto Endo, a young waiter, said he had spent much of the past few days in long lines waiting to buy food since he expects all the shops in town to run out of supplies and close soon. Since the restaurant where he works has closed, he has plenty of time on his hands.

“The lack of transport and the Fukushima problem are making sustainable life here impossible,” he complained. “I’m worried about my future, about my job, about my life itself.”

Mr. Endo, too, had heard that snow and rain could bring radioactivity down on his head, and said he was “very frightened for my health.”

But he would not leave Sendai for the time being, he said. “I might think about it if the danger level changed,” he explained, though he saw a risk of deciding too late to go.

Mr. Nohala, the construction worker, is not about to go anywhere either. “I’m worried for my family and I’d like them to leave," he said, “but I’ve got to work.

“Anyway,” he laughed, shrugging off the threat that any radiation might pose, “we Japanese eat a lot of seafood and seaweed. That’s full of iodine."