Indonesia's Aceh struggles to integrate former rebels fairly

| Banda Aceh, Indonesia

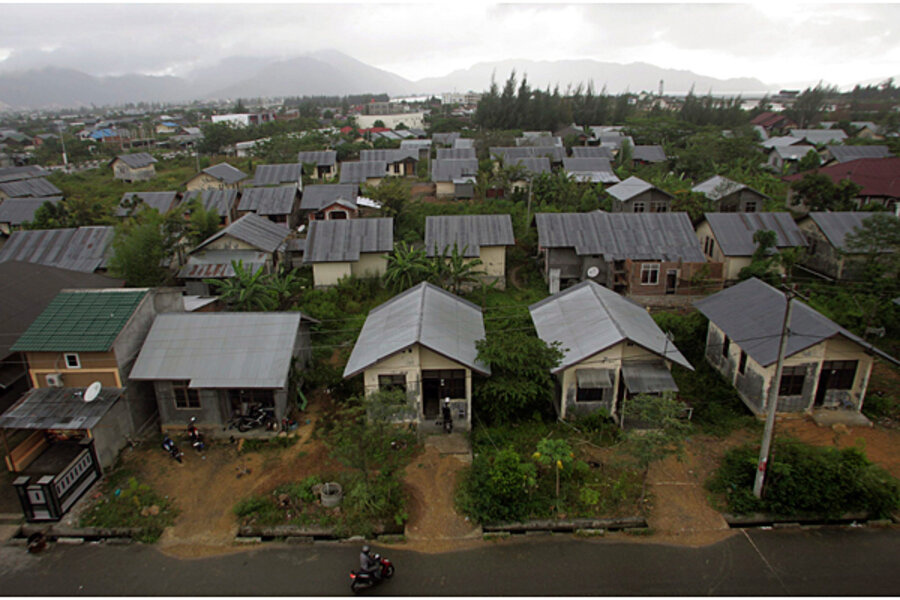

The misty terrain of this long-troubled Indonesian province is dense and arresting and laced with contrasts. Eight years ago gunfire riddled lush paddy fields. But today small mansions stand out among clapboard villages.

Home to a decades-long separatist insurgency, Aceh has been mostly peaceful for the past seven years. Last month former rebel Zaini Abdullah was elected governor of the province in largely non-violent polls that international observers called a successful test of the peace process.

With his win, Gov. Zaini Abdullah, the former foreign minister of the separatist Free Aceh Movement, known as GAM, gained control of the resource-rich land for which he and his group of rag-tag supporters fought for more than 30 years.

His entrance into politics, however, belies another fracture that has grown deeper recently, say analysts. Since the signing of a 2005 peace agreement in Helsinki that ended the fighting – in part by getting former combatants from GAM to lay down their arms and enter politics – the government has struggled to reintegrate ex-GAM members into society.

As this fragile province works to rebuild from decades of bloody battle – and a devastating tsunami in December 2004 – many analysts say feelings of injustice could deepen community divisions and spark violence from disgruntled ex-GAM who see the spoils of their struggle fall victim to nepotism and political corruption.

A return to wholesale, organized conflict is unlikely, says Ed Aspinall, a political professor who specializes on Aceh at Australian National University. But “sporadic, low-level squabbles over economic access” are “certainly possible.”

Many former rebels are unemployed, lacking basic skills needed to fish or farm, while money from a state assistance program aimed at easing the transition has been unevenly distributed.

Samsul Bahri, a cocoa farmer tasked with guarding his village during the rebellion, says he received a one-time lump sum of Rp 500,000 (roughly $55), a quarter of his current monthly salary.

“It’s nothing,” he says, explaining that funds from the reintegration program only went to two of the former combatants in his village, who then split them among the 30 others.

Within political circles, meanwhile, some former rebels have grown rich on lucrative development contracts in return for supporting provincial and district-level officials.

Powerful political brokers

Part of the problem comes from GAM’s former military wing, which was transformed into a transitional body popularly known as the KPA and tasked with seeing that ex-combatants got jobs.

A recent report by the International Crisis Group, which keeps a close eye on developments in Aceh, says that in some places the KPA has become, “a thuggish, Mafia-like organization.”

“Senior KPA members have not just received jobs; they have become powerful political brokers and businessmen demanding and usually receiving a cut on major public projects,” the Crisis Group report says.

The contrast is evident in Bireuen, a stronghold of former Gov. Irwandi Yusuf, who Abdullah officially unseated by winning 55 percent of the vote in April 9 elections.

Along the ruined road to the village where Bahri lives, a siren-red Mercedes Benz slinks by modest thatch-roofed houses. Elsewhere, homes with cathedral windows and gaudy statues sprout from rice fields.

Bahri says life is better now that he doesn’t have to carry a gun, but it bothers him that some of his former comrades have benefited so much more from the peace agreement than others.

“Before we were together as rebels, and now they’ve forgotten about us,” he says, casting his eyes down at the table before continuing. “Some ex-combatants, including me, feel it would be better to have war again so everyone would be equal.”

The 40-something farmer, whose rented house leaks when it rains, is clear that war would be a last resort – what he wants is justice. But the winner-take-all attitude displayed by many ex-combatants has made that goal increasingly onerous.

The spoils system

“The situation in Aceh is complicated,” says Fahrul Razi, a former academic and now key spokesman for Governor Abdullah.

During campaigning, Abdullah, a key negotiator in the Helsinki peace agreement, prioritized fully implementing the terms of that treaty. He also spoke of ensuring peace and economic development.

“The key to peace and development is economic programs,” says Mr. Razi, who fails to elaborate on what type of programs the new governor has planned but is eager to discuss how Yusuf’s favoritism and desire for personal enrichment have held back Aceh’s progress.

“Only 20 or 30 people close with [him] have benefited,” he says.

Yusuf, an Oregon-trained veterinarian who drives a Honda Prius – a rare sight in this impoverished province – gained popular support by implementing a health insurance program, and providing assistance in the form of school scholarships.

He also helped temper the KPA’s use of intimidation and extortion, but many of his confidants have won contracts for government development projects, such as bridge and road construction.

On the day before the recent election, a dozen of them gathered at his lavish home in Banda Aceh – Yusuf opted not to live in the governor’s residence. Dressed in button-up collared shirts and sporting gold rings and watches, they sipped coffee near a swimming pool hidden behind high walls.

“For the first two years I focused on them, on how to quell them, so any direct funds within my authority were mostly directed toward them,” says Yusuf, who explains that such assistance was needed as a way to ease their transition out of fighting.

'It should have come from the state'

Under the 2005 peace agreement, Jakarta agreed to set up a special autonomy budget that would be used to fund development and provide economic assistance to former combatants.

The GAM leadership at that time provided a list of 3,000 names to the Aceh Reintegration Board (BRA), the agency tasked with handing out reparations of $2,700 a piece to top-level GAM members. But its head, Hanif Asmara, estimates that as many as 40,000 people provided support to the rebels and deserve some type of assistance.

“All of them should get jobs and money,” says Mr. Asmara, who partially blames the KPA’s military-style structure for preventing the creation of a more equitable system that ensures all former rebels have legitimate employment.

Development programs have helped ease some tensions. Bahri, whose family owned a cocoa farm before the conflict, has received skills training from Swiss Contact, an organization focused on livelihood support. He now leads a group of 33 cocoa farmers and gives demonstrations to others on how to start planting. He says he does this out of a sense of solidarity with other ex-combatants.

If that unity holds it could bode well for Aceh, which currently has some of the highest poverty and unemployment rates in Indonesia. Its port, built in part with donor money, is impressive but quiet. Most trade still goes through Medan, a 12-hour drive south of the capital Banda Aceh over narrow, winding roads. Agriculture is the only industry that has registered growth in a place rich with oil, gas and other natural resources.

The next few years will be a test of the local government’s staying power, says Aspinall. “The fact that these issues have not been resolved or are unlikely to be resolved adds an extra layer of delicacy,” he says

Get daily or weekly updates from CSMonitor.com delivered to your inbox. Sign up today.