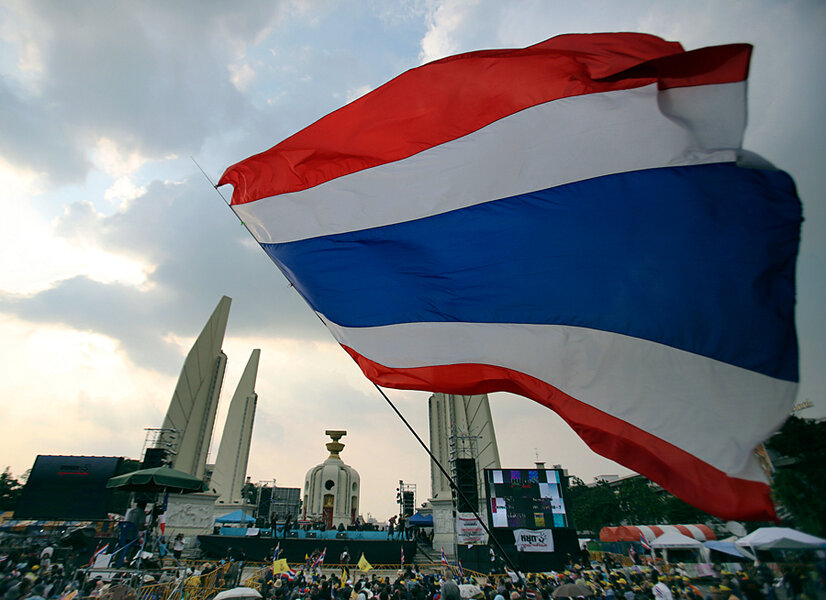

Thai political amnesty bill defeat: An end to protests?

| Bangkok, Thailand

There was calm on the streets of Bangkok on Tuesday, a day after the Senate rejected a controversial bill that would have provided amnesty for political offenses in Thailand stretching back almost a decade.

The bill, proposed by the governing Pheu Thai party, was intended to bring about reconciliation after years of political turmoil.

Instead it prompted weeks of mass protests by tens of thousands of Thais across the political spectrum. The protesters said it would exonerate politicians, including Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra’s brother, former premier Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted by the military in 2006, as well as soldiers and political leaders who oversaw a deadly crackdown on demonstrators in 2010.

"[The Amnesty Bill] can not be. It will not be, we will not give up," said Praporn Tongchalermyuthana, one of a few thousand protesters who came out to celebrate the victory on Tuesday.

There’s a feeling that the government fatally misjudged the level of opposition the bill would provoke. Pro-democracy leaders have congratulated demonstrators on their success in maintaining the accountability of the country’s political elite.

The Senate result has eased immediate fears that the protests could spark mass violence of the kind seen in 2010, when more than 80 people died in clashes between anti-government demonstrators and the police.

However, political and economic analysts remain cautious on what the episode means for long-term stability in Thailand. Opposition leaders are calling for civil disobedience and a three-day general strike starting Wednesday.

“Whether this is a victory for democracy will depend entirely on what happens in the next few weeks,” says Bangkok-based political commentator and journalist Voranai Vanijaka.

He says the vast majority of protesters were ordinary citizens who will go back to normal life now that the bill has been rejected. If this happens it will be a broad victory for the body politic in Thailand who will have proven their power to influence decisions and register their disapproval without delegitimizing the political system.

“But if the hard-liners insist on pushing this into further protests with the aim of bringing down the government entirely, that would be a very bad thing for democracy,” says Mr. Vanijaka.

Thai political scientist Thitinan Pongsudhirak goes further, warning that the protests are evidence of serious instability in the entire political system.

“This cannot be good for democracy in the long term,” he says. “The latest protests are merely a recurrent pattern in Thai politics where one side wins the election with a decisive margin but can be prevented from ruling by a minority who will use extra-parliamentary means to force their agenda.”

Mr. Pongsudhirak says the only way to improve the political system in Thailand is to encourage a strong and legitimate opposition who rely on elections to push their agenda.

Unfortunately he says, the opposition Democratic Party has lost legitimacy during the recent protests by playing the roll of “street mob,” calling for the collapse of the state.

“They have set a dangerous precedent which, if they ever win a legitimate election, could easily be used against them.”

Whether the threats for further action will materialize will depend in part on how the government responds to the rejection of the bill in the next few days. Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra has promised to honor the result from the Senate. However, the bill will return to the lower houses of Parliament, where in theory it could be resurrected after 180 days.

On Tuesday Democrat Party MPs called for a three-day national strike to put pressure on the government over the rejected amnesty bill. Pro-government supporters responded by saying they would hold rallies in the city’s largest park over the next few days. Meanwhile, the leader of the pro-Thaksin Red Shirts vowed to bring 100,000 protesters to Bangkok early next week.

The recent instability is already having a negative impact on Thailand’s financial markets and all important tourist industry.

Sixteen countries including England, France, Israel and Japan warned their citizens against traveling to areas in Bangkok affected by the protests, Thailand’s tourism board said on Tuesday.

Meanwhile the Board of Trade of Thailand (BTT) called for all sides to refrain from confrontation and violence that could damage investor confidence in the country and damage Thailand’s image in the long term.