Pakistan: Pashtun hospitality for 19 adults, 25 children, and four camels

Loading...

| Swabi, Pakistan

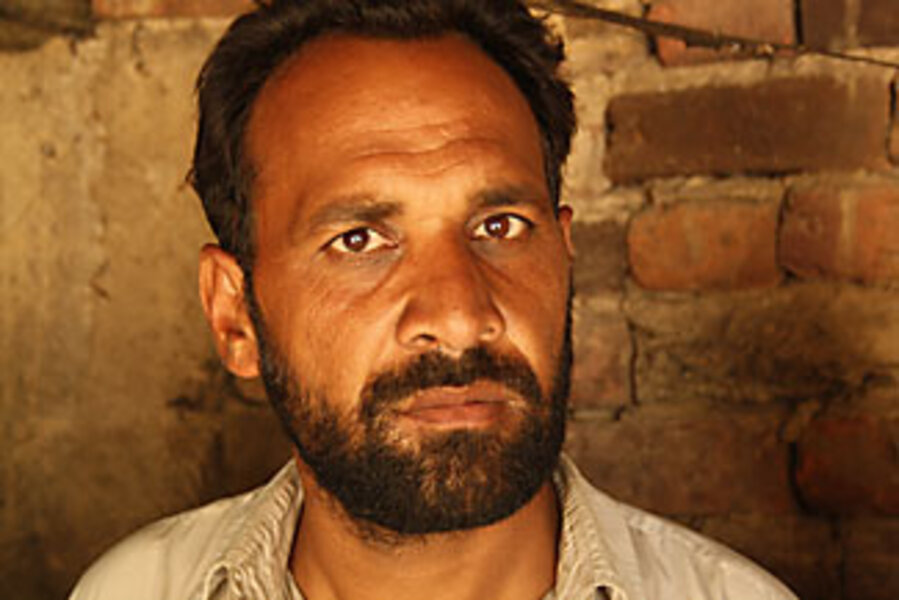

Nightfall was closing fast and Hussein Gohar's clan of 19 adults, 25 children, 4 camels, and 4 buffaloes felt every inch of the 37 miles they had just walked.

They had escaped the fighting between the Pakistani Army and Taliban forces in the hills of Buner, but as Mr. Gohar explains now, they were just following a road: "We had no destination."

That's when Zarnosh Khan and Sher Wali Khan – two wheat farmers in the valley city of Swabi – spotted the group two weeks ago.

"We didn't know them [but] it was evening and the kids were with them. So we thought, 'Where will these people go? Let's give them shelter,' " says Zarnosh. Added Sher Wali: "If we were put in a situation like this, then we would also expect help."

Neighbors brought portable fans from the mosque and food, utensils, cots, and carpets from their homes. They set up the Gohar clan in the hujra, the Pashtun equivalent of a neighborhood community center.

Strangers are opening doors to strangers all across the Pakistani communities that lie in walking distance from Swat and Buner, easing the burden on the crowded official refugee camps. Residents say their hospitality traces back to an ancient Islamic practice known as muakhat, as well as pashtunwali, the ethnic code of behavior that in different circumstances has led some Pashtuns to shelter fleeing Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters.

Culture of hospitality

"It is a religious duty [and] it is also the culture of the Pashtuns that you give shelter to guests and the needy," says Muhammad Saleem, a doctoral candidate researching the region's social safety net. "When the state is absent from these duties, people have to fill in the gaps."

The state is also responding. On the outskirts of town, a refugee camp named Chota Lahore now houses more than 5,000 displaced people with an average of 90 new families coming each day. The camp offers four meals a day, makeshift schools for girls and boys, and 98 latrines. But it's located in an isolated, hot, dustbowl – generating complaints that have prompted authorities to order it moved to a new spot that can hold 14,000 people in tents.

Overall, the number of people displaced by the conflict stands at more than 500,000, according to United Nations figures. Some Pakistani officials Wednesday put it at 800,000.

In a repeat of scenes after the devastating 2005 earthquake in northern Pakistan, residents have been driving up to the camps to drop off food, drinking water, and hand fans, says Mr. Saleem. He and a group of students back at his university in the Netherlands have pooled together 3,500 euros, which they will use to buy supplies: pillows, lighting, mattresses, and hand fans.

But perhaps the most impressive donations are the open doors.

Making room for 150 guests

Fazli Rabbi, a farmer in Swabi, welcomed some relatives from Buner into his home, providing lodging for 150 people.

It's meant a few adjustments for his family of 13. The family removed all the beds and laid down carpets to sleep on instead. The kitchen in his 2,000 square-foot home no longer suffices, so they now cook outdoors. The baking of bread in a tandoor oven – a chore that once took 30 minutes – now stretches from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

The timing of this influx of guests couldn't be better. Farms in Swabi have just finished harvesting their wheat and now enjoy a lull before the next planting season. Each day, the refugees staying here make a trek over to the official camp in the hopes of getting some food and any supplies to ease the burden on their hosts. Each day, they come back empty-handed.

"We need a ration card to get something, but it's very hard to get a card," says Zarjamil Khan. "People who are in the camps, they are in real trouble. Compared with them, we are very blessed."

Neighbors are putting up other refugees who fled together as a group from Buner. Fifteen men sleep in the mosque, the women and children have been given lodging in the hujra. Local doctors came and gave out 14,000 rupees worth of medicine and tended to the shell-shocked children. For now, the vegetables of the farm are tossed into a huge pot and boiled, recreating a daily loaves-and-fishes miracle of sorts.

Islamic roots of hospitality

For the Muslim residents here, the religious parallel is to the flight of the prophet Mohammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. To make sure all were provided for, Mohammad set up a system known as muakhat – "brotherhood" – where he paired one resident of Medina with one resident of Mecca and declared them brothers. Henceforth, the brother in Medina would share his home and his livelihood with his brother from Mecca.

Zarjamil is grateful for the brotherhood of his distant relatives and the strangers in the neighborhood.

"The locals here have taken every burden on their shoulders to help us," he says. "This is both Islamic and pashtunwalli, and if this kind of situation came on these people then we would also help them."