Is there room for India's nomads?

Loading...

| Dehradun, India

It was just before 2 a.m. when Dhumman Kasana knelt and prayed, facing west, toward Mecca. The mud walls of his family's hut glowed in the flicker of a kerosene lamp. Tea brewed over a fire. Milk was being sloshed into butter. Children asleep on the floor were prodded by elder siblings who were packing the burlap bedrolls: Time to get moving.

Twice Dhumman interrupted his prayers, advising his sons about loading the bullocks with the family's belongings. He closed his devotion by asking Allah to help his family and their 44 water buffaloes on the journey ahead. They travel the same route every April, migrating from the lowland forests of India's Shivalik hills up to their summer meadows in the Himalayas, following in the footsteps of countless ancestors. But Dhumman feared trouble this year. Government agencies in charge of his clan's traditional pastures had threatened to block them from entering, in the name of environmental preservation.

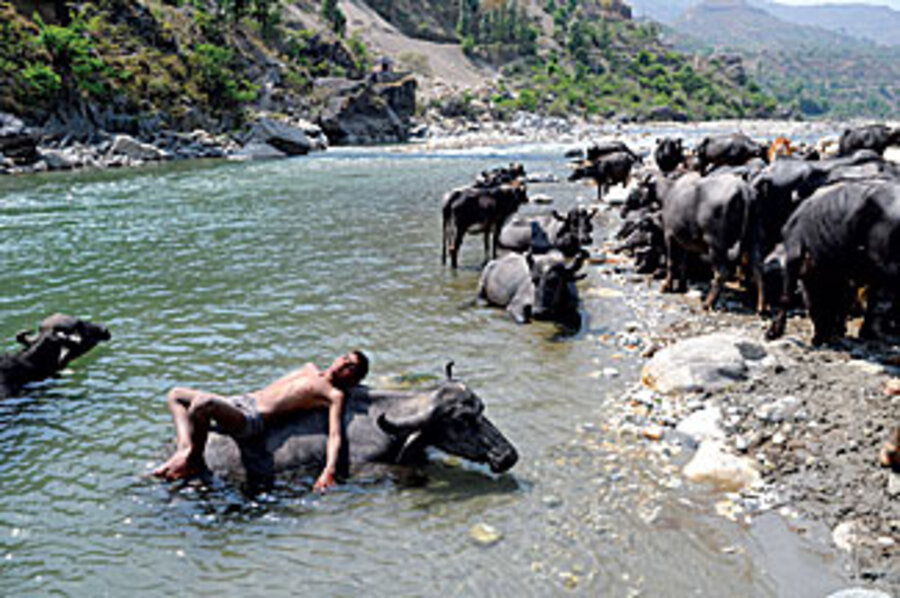

His family is Van Gujjar, a tribe of nomadic buffalo herders who've migrated across north India for at least 1,500 years. Today their population is estimated at between 50,000 and 70,000. Concentrated today in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, they base their livelihood entirely on buffalo milk, which sells for between 14 and 22 rupees (30 to 45 cents) per liter. Though Muslim, they're vegetarian and would never eat or sell their animals for slaughter: They love buffaloes and treat them like kin, even burying them when they die.

"They come when you call their names, and when you give them affection, they return it, almost like people," explains Sharafat, Dhumman's 16-year-old son.

During winter along the border of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, the serrated Shivalik hills are covered with leafy trees; Van Gujjar teens scamper barefoot up the highest branches, deftly lopping leaves to feed their herds. By April, the heat rolls in; creeks run dry and leaves wither. The buffaloes need to head for the bugyals, the grassy alpine meadows of the Himalayas. Families, including infants and pregnant women, trek hundreds of kilometers to reach the highlands. When the snows return, the families and their herds descend.

For generations, this has been the cycle of Van Gujjar life. But it may not remain so much longer.

Many Van Gujjar grazing areas have been incorporated into wildlife sanctuaries and national parks, and India has long followed a conservation policy of "no people in parks" (except tourists). Since the creation of Rajaji National Park in 1992, park authorities have pressured the Van Gujjars who winter there to settle in villages and learn to farm. Despite years of protest, 1,390 families have been relocated from Rajaji to settlements, where buffalo herding is impossible and their nomadic culture can't survive.

Dhumman's clan is among the few thousand Van Gujjars who winter just west of Rajaji. But their alpine pasturage, 120 miles farther north and 8,000 feet higher, where Dhumman has spent his 51 summers, has been absorbed into Govind Pashu Vihar National Park. Uttarakhand's forest department, which manages the park, has resisted admitting Van Gujjars. Aside from environmental concerns, they assert that they don't want Uttar Pradesh "outsiders" using state resources. (Uttarakhand was part of Uttar Pradesh until 2000.)

When Dhumman, his wife, Jamila, and their seven children started their migration to high pastures in April, the forest department hadn't yet issued entry permits for the summer territory. Dhumman's family walked north along the Yamuna River, accompanied by the families of his brother and a cousin, on a route followed by hundreds of Van Gujjars. None knew when, or if, permits would be approved. As days passed, bringing them closer to a possible blockade at the park entry, anxieties mounted. To linger too long in one place, they'd run out of fodder for the herds; to move too quickly, entering their pastures without permission, they'd face arrest and fines. In late April, park officials declared, "[T]here is no possibility of allowing these Van Gujjars entry into Govind Pashu Vihar."

On reaching a fork in the route, with no sign of compromise by park officials, Dhumman decided to head somewhere different this summer, where maybe a couple thousand rupees (around $50) and a few liters of milk, given to a ranger, was all the permission they'd need.

Fighting their eviction from parklands, Van Gujjars insist that they're a natural part of the environment and help maintain balance within the forests they rely upon for survival. They assert that because they've been returning to the same areas for hundreds of years, their grazing practices must be sustainable. Conservationists, however, point to the substantial size and appetite of buffaloes as surely destructive to forests and grasslands.

"Buffalo herders are banned from the park because overgrazing and trampling causes environmental degradation," says G.S. Rawat, a professor at the Wildlife Institute of India.

The actual environmental impact of Van Gujjar herds has never been determined, says Nabi Jha, a scientist studying alpine grasslands in Uttarakhand. "We need to measure the land's carrying capacity against the buffaloes' demands before we'll know if there's any reason to ban Van Gujjars or limit their numbers. Rotational grazing is often good for these meadows."

In mid-May Uttarakhand park authorities abruptly reversed themselves, allowing Van Gujjars to enter this year. It was two weeks too late for Dhumman, who was by then deep in an unfamiliar forest to the east, too far to reverse course.

The tribe's future hinges on whether its families will be recognized in Uttarakhand as beneficiaries under India's Forest Rights Act of 2006, which grants rights to "traditional forest dwellers" to the lands they've relied on for generations.

In Uttarakhand, the act is scheduled for implementation this year. If Van Gujjar claims are legitimized by committees established by the state's Tribal Welfare Department, their right to migrate should be assured; if their claims are denied, future migration will become more difficult, as families will have to scramble for new summer pastures and might be completely shut out of the highlands for good. For Dhumman, this year was hard enough. Usually, his migration lasts about 20 days. This time his family was on the trail for 40. Along the way, children fell ill and pack animals went lame, sometimes forcing men to shoulder full saddlebags on the trail. Once, a hailstorm swept a tree off a cliff; it fell on a young buffalo, crushing its leg. Refusing to abandon it, Dhumman splinted the leg, and the buffalo was carried over a 12,500-foot mountain pass.

Upon reaching a ramshackle hut perched on the grassy slope where they'd spend the summer, the family was disappointed. The roof and walls would have to be repaired before it could meet the definition of shelter, and Dhumman's brother's family would have to build an entirely new hut nearby. Compared with their usual camp, 4,000 feet lower, everything was more difficult. Weather was temperamental, and ice coated their tent at night. They were more than 15 miles (and 6,000 feet in elevation) from the nearest village where they could buy provisions, so food was rationed and everyone was perpetually hungry. But perhaps worst of all, for which even the staggering views of the snow-covered, 20,721-foot Bandarpunch massif couldn't compensate, it just didn't feel like home.

The stress of the journey had taken its toll. Jamila, Dhumman's wife, suggested she'd be open to a government settlement program – long anathema to the fiercely independent Van Gujjars – if one was offered: "I never wanted to settle before," she said, "because we used to be free to move around.... But now we have no security. Living in a village, sure, we'd lose a lot, but at least we'd know where we'd be."