Earthquake prone Japan sees green in new nuclear power plants

| Tokyo and Matsuyama, Japan

Japan is pressing ahead with an expansion of nuclear power, despite public unease and vocal opposition from activists.

Poor in natural resources, the country has long dreamed of reducing its fossil fuel dependency through domestic nuclear power. Now it's casting nuclear energy as a key to the fight against global warming, an argument that critics reject.

Japan's debate closely mirrors those worldwide, as governments highlight nuclear power as an easier way to cut carbon emissions than boosting wind and solar power.

President Obama, for example, on Feb. 16 announced $8.3 billion in loan guarantees to build the first nuclear reactors in the United States in 30 years – the first of many, he promised.

Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama has pledged to cut Japan's carbon emissions to 75 percent of 1990 levels by 2020, if other major economies set similar targets. His government recently backed a plan for low-interest loans for new nuclear reactors.

"If we want to do this 25 percent reduction, obviously we need more nuclear plants," says Shunsuke Kondo, chairman of Japan's Atomic Energy Commission.

But the public isn't entirely convinced. According to the Japanese cabinet's own poll last November, 54 percent say they feel anxious or uneasy about nuclear power, with the top concern being the risk of an accident. Forty-two percent said they feel "safe" about nuclear power.

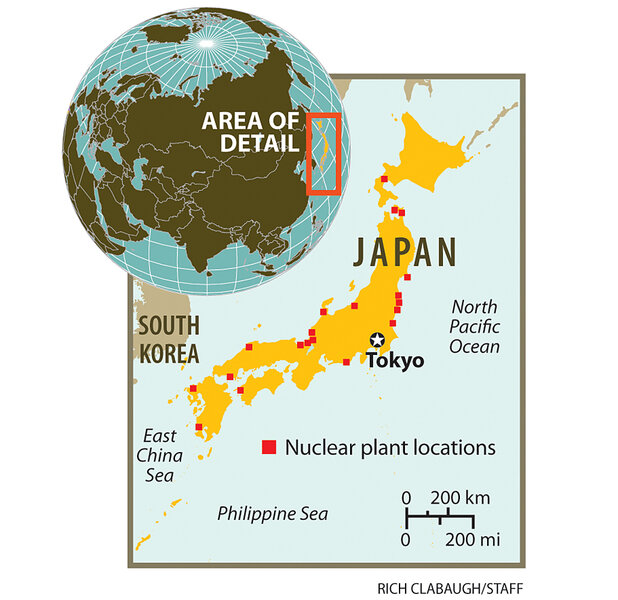

Meanwhile, activists criticize Japan's nuclear program as dangerous, expensive, and impractical. One concern is Japan's earthquake-prone geology, which they cite in raising the specter of a quake-induced Chernobyl. Just on Saturday, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake hit off Japan's southern coast, shaking Okinawa and nearby islands and rupturing water pipes.

In recent months, activists have focused their ire on the government's introduction of "pluthermal" fuel in nuclear plants. The term refers to the use of mixed uranium-plutonium fuel known as MOX (mixed-oxide) fuel.

The government touts pluthermal as a way to reuse spent fuel, saying it's more efficient and produces less high-level radioactive waste than normal reactors. It first introduced MOX fuel at a nuclear plant last year. That drew weeks of protests from activists.

A second plant, at Ikata, near the port city of Matsuyama, is set to use MOX fuel in March. "MOX fuel is many times more dangerous than uranium fuel," says Makoto Kondo, a longtime opponent of the Ikata plant. "When it comes to blasts or accidents, far more devastating damage would occur with pluthermal reactors."

Ambitious plans

Officials acknowledge they must work harder to win public trust. But they insist that nuclear plants are safe.

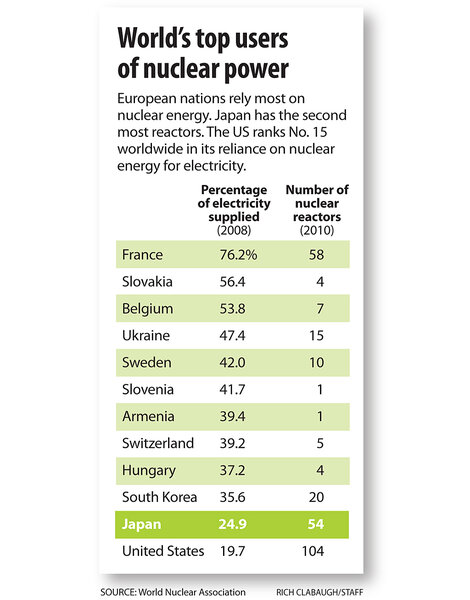

Japan now gets about a third of its electric power from some 54 nuclear power plants. It hopes to build eight more by 2018, boost capacity at its existing plants, and upgrade more plants into pluthermal ones.

The Atomic Energy Commission's Mr. Kondo and other officials say using MOX fuel allows Japan to recycle its energy resources. Japan currently sends spent fuel to Europe, where it is reprocessed into MOX fuel and shipped back. "The simple reason for using plutonium is because we want to use our resources as best as we can," Kondo says, adding that MOX fuel has been used safely in Europe for years.

He says Japan's plants were built to withstand all but a "once in 10,000 year" earthquake. But he acknowledges that since Japan switched on its first reactors in the 1960s, three quakes have produced vibrations exceeding design assumptions. (Large safety margins in construction prevented any major accidents in those cases, he says.)

According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), nearly a third of Japan's planned carbon reduction targets by 2020 will come from nuclear power, making it the biggest source of carbon-emission cuts after energy conservation (60 percent).

In contrast, the government expects less than 6 percent of cuts to come from renewable energies.

"Nuclear power is one of the important sources of Hatoyama's target," says Katsuyuki Tada, a deputy director at METI.

For Japanese planners, the goal is to achieve a self-sufficient "nuclear cycle," with fast-breeder reactors sending spent fuel to Japan's own reprocessing plants, to be turned into MOX fuel.

Public opposition

But critics say it's a costly and risky pipe dream. The fast-breeder reactor program is technically daunting and has been plagued by delays; 2050 is the current target for commercial use.

Japan is set to begin reprocessing this year or next, after many delays, and hopes to produce MOX fuel by 2015.

There's also a proliferation and terrorism risk. MOX fuel is a tightly regulated material that could be used to make a "dirty bomb." It's transported by custom-built, armed ships with an elite police detail.

Disposal is also a question. Like many countries, Japan has yet to establish a permanent storage site for high-level radioactive waste, and "not in my backyard" sentiment runs high.

But as even the activists admit, those concerns don't look likely to dissuade the government.