Planting saplings in tree-starved Mumbai 'is the least I can do.'

| Mumbai

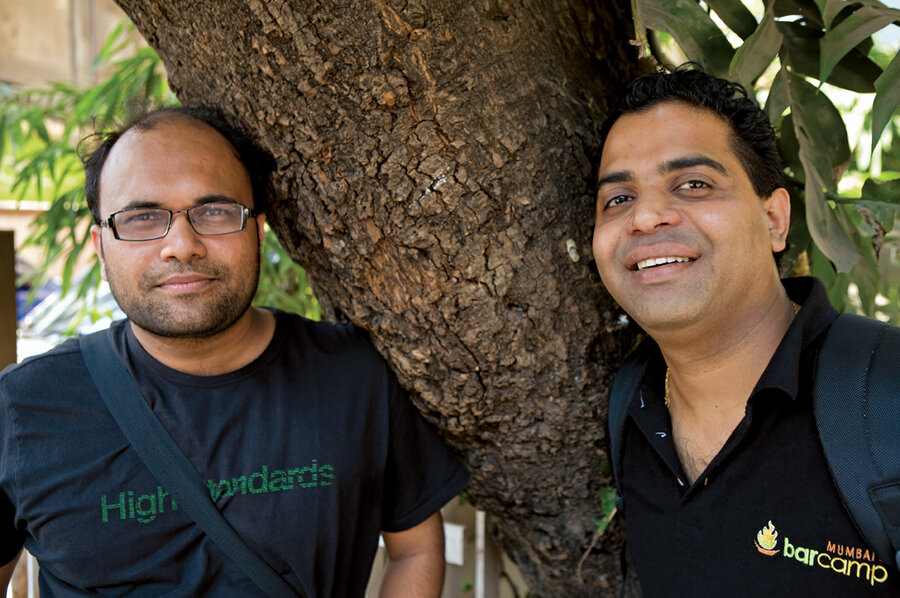

The seed of the idea, Satish Vijaykumar recalls, started as something tiny and simple. But quite unexpectedly it has sprouted branches that touch hundreds of people in cities across south India and as far away as Zimbabwe.

"One day I was just sitting and thinking how the average Indian is always worrying about something, but we don't do anything," he says. As a young adult living in Mumbai (Bombay), he found that one thing that seemed doable was to pool rupees together with friends, buy a few tree saplings, and plant them. "It's the least I can do," Mr. Vijaykumar thought.

He told his buddy, Ranjeetsinh Walunjpatil, who suggested they put the idea on a website and give it a voice on Facebook and Twitter. Friends, then friends of friends, became fans and promoted it. Journalists noticed the buzz and wrote stories. Money arrived. Before they knew it, Vijaykumar and Mr. Walunjpatil were taking a van one weekend across Mumbai, dropping off hundreds of trees to strangers.

The Sapling Project, as it's now called, is neither flashy, nor grandiose, nor particularly original. But it provides yet more evidence for a basic law in the physics of making a difference: People at rest tend to stay at rest until one person starts things rolling.

"The world is full of nice people – the only thing is to get them motivated," says Vijaykumar, who reckons that everyone has the potential to nudge along at least 10 people in their life. "If your cause is good, people will go out of the way to help you."

So far The Sapling Project has delivered 1,200 trees, with two large deliveries in Mumbai and one each in Bangalore and Chennai with the help of friends in those cities. Some 600 to 700 people have become involved. The goal is to plant 10,000 trees, preferably before the monsoon, then expand into other Indian cities such as Pune, Hyderabad, and Ahmedabad.

The cofounders are also working to establish the project as a nonprofit group. For every 44 cents donated, a neem or other tree sapling can be planted (33 cents for the tree, 11 cents for fuel and logistics).

People who want a tree can take one free of charge from a van as it passes through the city. There are only two conditions: Plant the sapling in your area and tend it for two years until it takes root. "Our cities are losing trees. It's becoming difficult for people to breathe," Vijaykumar says.

In Mumbai, a megalopolis of 14 million people elbowing for space, trees are losing out to development, according to forest advocates.

The government has conducted two tree censuses. The latest figures show 1.9 million trees in the city. But the numbers are disputed since they include dead trees and invasive species, and the methodology has changed between the counts, rendering the data useless for spotting trends. A new census is under way using global positioning system technology.

"The amount of building activity that is coming up in Mumbai is unprecedented, and nobody has actually quantified [deforestation]," says Debi Goenka, leader of the Conservation Action Trust, a Mumbai nonprofit that has fought to protect the city's mangroves and a national park that lies within the city limits.

Once a month the city's tree authority approves the felling of 3,000 to 4,000 trees for various projects, Mr. Goenka says.

If those numbers would show up in a census, he says, "There would be an uproar."

Goenka lauds The Sapling Project, while alleging that the city has a lot of money earmarked for tree planting that it is not spending.

But Vijaykumar and Walunjpatil aren't interested in fighting city hall.

"Many people have commented, 'Why is government sleeping?' But ... every time you can't blame government. What have you done?" Walunjpatil says. The two say they are now in talks with city authorities about working together on tree-planting projects.

The project continues to grow. America.gov, a US State Department website, has interviewed them, and US officials have asked the two to share their idea with people in Kenya and Zimbabwe.

In one corner of Mumbai, their project indirectly helped dozens of kids collect wastewater from their kitchens to water the saplings. That happened after stay-at-home mom Veeni Bhagat was looking for free saplings and stumbled on The Sapling Project's website.

Ms. Bhagat decided she would turn her green thumb to reclaiming a litter-strewn open space behind her apartment building. She enlisted children from her building. Each adopted a tree from The Sapling Project and waters it using gray water from their apartment.

The project has given the kids a safe place to play outdoors and also taught them a few lessons. "Each child adopted their own plant. That is how they learn awareness that they should grow plants and take care of them," she says.

Such open spaces are rare now, she notes, gazing across the highway at a call center office tower built two years ago. She hopes the trees will help block noise from the road, provide fresh air, and, in a small way, combat climate change.

Just cleaning up the lot inspired her neighbors to see the land differently: They chipped in to buy playground equipment.

"India's greatest strength and its weakness is its people. We've got 1.2 billion of them. It's time we used that 1.2 billion as an asset," Vijaykumar says.

"Imagine having even 1 percent of that population as ecowarriors or propagating something nice for the environment?"

• Learn more at thesaplingproject.com

• For more stories about people making a difference, go here.