A new party emerges in world's biggest democracy

| New Delhi

The world's largest democracy gave birth to a new political party today, this one focused on fighting corruption.

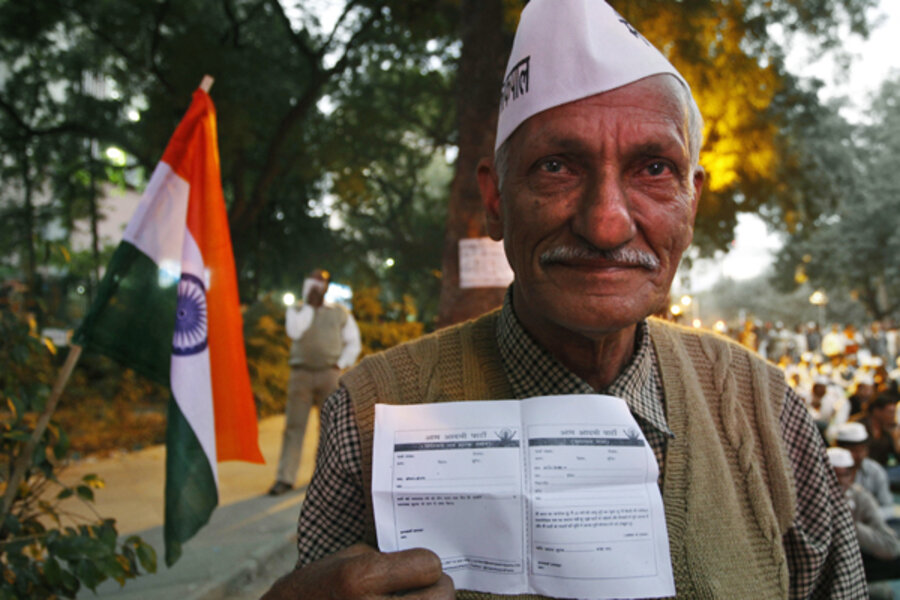

At a public rally in India's capital of New Delhi, supporters all wore white Gandhi caps with ‘I am common man’ written on them in Hindi. They spoke of the Gandhian slogan of "swaraj," or people’s rule. They promised to free India of corruption and provide an alternative to the two main national parties, the centrist Indian National Congress and the right-wing Bhartiya Janata Party.

The public launch Monday of the AAP, or Aam Aadmi Party ("Common Man’s Party"), marked a culmination of India’s anticorruption movement that began in April 2011. That movement was compared to Occupy Wall Street by some. It was led by the Gandhian social activist Anna Hazare, but spearheaded by Arvind Kejriwal, a tax officer turned freedom of information activist turned anticorruption activist. The new party is Mr. Kejriwal's brainchild.

The Hazare movement had chiefly demanded the creation of a Lokpal or anticorruption ombudsman, amid innumerable corruption scandals that have rocked the ruling Congress-led coalition. But Mr. Kejriwal’s decision to turn the movement into a political party earlier this year saw Hazare splitting ways with him.

The AAP – which is also the Hindi word for ‘you’ – says it will not allow political dynasties to make use of their party, will have women at every level, pass legislation for electoral and judicial reform, curb rising prices, and involve the public directly in policymaking. A statement by the party said it was entering politics because the country's politicians had failed to create an anticorruption ombudsman.

While the launch of the party brought out committed followers of the movement, many are skeptical about its prospects in a country where parties command the loyalty of voters on the basis of caste and ethnicity. The AAP is trying to be an umbrella party with issues and ideas that would appeal to everyone, such as corruption and accountability. But will these translate into votes?

One of the party’s supporters at the rally on Monday, Rajesh Gupta, is a businessman who says that he hopes the party’s plank would make people rise above caste and communitarian patterns of voting. “Vote-banks are not fixed,” he says, “If they were, we wouldn’t see governments change.”

Zoya Hasan, who teaches at the School of Social Sciences of the Jawaharlal Nehru University and has studied party systems in India, says it is early days yet to tell whether the party will make any electoral impact.

“At the moment, it doesn’t look like they are going to matter in the elections. Their keywords – common man, people’s rule – are all borrowed cliches of Indian politics,” she says. Their vision document contains nothing new, she says, except for the promise of decentralizing power.

Yet the leaders of the party have surprised analysts before. In the runup to the formal launch of the party, Kejriwal and his lawyer colleague Prashant Bhushan leveled attacks on powerful people over corruption. These included the Congress party president Sonia Gandhi’s son-in-law Robert Vadra and the richest Indian, industrialist Mukesh Ambani. Mr. Vadra and Mr. Ambani are not often questioned even by the media. Further corruption allegations some weeks ago against the chief of the Bhartiya Janata Party, Nitin Gadkari, have resulted in a crisis that the party is yet to recover from.

“Given the kind of drift in the major national parties, the AAP may have some chance in the big cities, which is where they have shown they can mobilize the youth,” says political commentator Ajoy Bose. He added that the experience of others shows that creating a party is a long-term project, one that may take decades.

While new parties come up all the time in India’s multiparty system, the AAP is different as it is being started from the national capital with pan-India ambitions, rather than focusing on a single region. General elections are due in 2014, but the AAP has set its first test in the Delhi state assembly elections in 2013.

Political scientist Nivedita Menon says that this party’s success should not be measured by its future electoral politics. “What is more significant is that they have the potential to change the idiom of Indian politics,” she says.

And then there are those who think that trying to change "the system" is futile. Novelist Arundhati Roy, known for her radical criticism of the Indian state, told Outlook magazine in a recent interview, “Change will come. It has to. But I doubt it will be ushered in by a new political party hoping to change the system by winning elections. Because those who have tried to change the system that way have ended up being changed by it – look what happened to the Communist parties.”