Could India's polio eradication success story be a model for its other health issues?

Loading...

| MUMBAI, India

Setarah Khatoon was 15 when she left school to marry a boy from India’s northeast state of Bihar. She was barely 16 when she had her first miscarriage, and by 20, she'd had two more. So when the mother of one surviving baby girl saw Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan’s television ads telling parents that just “two drops of medicine” could help keep a child alive for life, Ms. Khatoon took her infant to the nearest pharmacy and asked how to vaccinate her only child against polio.

“Two drops of life,” she immediately recalls at her tiny apartment in a housing colony within M-Ward, Mumbai’s poorest and least developed collection of government resettlement buildings and slums. Khatoon says the pharmacist she found directed her to a nearby clinic run by a local nongovernmental organization, Doctors For You. There, her infant became the first in their family to get vaccinations, and Khatoon herself got access to regular medical check-ups, information about nutrition, and if she wanted it, birth control.

Advertisements such as those that prompted Khatoon to seek help are part of an unprecedented campaign by the central government in New Delhi and India’s state governments to eradicate and keep wild poliovirus out of India. This January marked the second year that India, long considered a major exporter of poliovirus, did not record a new case of the infection – leaving Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria the last countries still battling the disease.

Now, as India looks set to be considered officially "polio free" by the end of this year, health officials are considering the successful combination of advertising and government buy-in a promising model to apply to other health initiatives in the country.

On the verge of polio-free

In the 1940s and 1950s, polio was considered a global epidemic, with thousands of new cases arising each day throughout the world. Families in the United States kept their children out of public places such as parks and swimming pools, worried they would catch the disease. Between 1950 and 1954, doctors say some 22,000 US citizens were paralyzed by the virus. In 1952, the same year scientists developed an effective polio vaccine, almost 58,000 children were reported to be infected in the US alone, leaving 3,300 dead and thousands paralyzed.

In India, the journey toward eradicating the disease has been a long one. By 1988, when the World Health Organization (WHO) passed a resolution to eradicate polio, 1,000 people a day worldwide were still being stricken by the virus. India accounted for around half that, with 450 children infected with polio every day, says Deepak Kapur, chairman of Rotary International’s India PolioPlus Committee.

In 1994, when the health minister in New Delhi agreed to conduct a pilot mass vaccination program there, Indian officials finally garnered the political will necessary to spread the vaccination drive to the rest of the country, according to Mr. Kapur. The success of the Delhi vaccination campaign convinced central officials that it would be worth the money, resources, and massive labor force necessary for India’s state governments to drive the program forward on the ground.

“They thought this could not be done,” he says. “But the campaign was successful.”

Collaborating with organizations such as Rotary International, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization, the Indian government has waged a targeted battle against the disease, teaming up with local religious leaders, medical providers, universities, teachers and even Bollywood film stars, to advertise and administer polio vaccine nationwide.

Between 1988 and 2009, as the number of polio-endemic countries fell from 125 to just four—reducing the global number of cases from 365,000 to about 1,500—India still harbored half the world’s polio infections. In 2010, the number dropped to just 42, and India reported its last new case of poliovirus in 2011, says Kapur. If no new cases are recorded by the end of this year, India will be officially considered polio-free.

'Health cannot be seen in isolation'

Still, medical professionals say that weak health infrastructure, endemic under-nutrition, and inadequate water supply and sanitation remain serious public health challenges. India also faces the special task of tracking massive internal migration, as labor workers and their families move back and forth across state lines searching for work.

More than 1,300 children under age 5 die every day in India from pneumonia and diarrhea, conditions that can easily be avoided, according to Ajay Khera, deputy commissioner for child health and immunization at India’s Health Ministry.

“Health can not be seen in isolation,” he says. “Water supply, sanitation, the environment: Everything plays a role.”

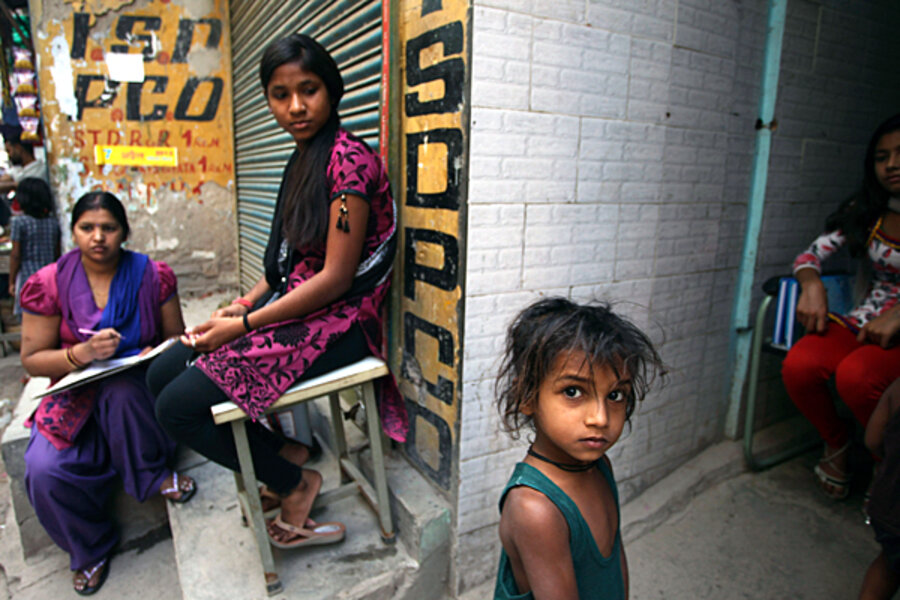

The Maharashtra Housing and Areas Development Authority slum resettlement in Govandi, where Khatoon lives, represents a microcosm of longstanding health challenges that remain. Water runs for about half an hour a day and electricity lasts three hours. So, while residents have to haul buckets of manually pumped water up and down several flights of stairs each day, they’re easily able to keep televisions and rechargeable electronic items such as cellphones.

Families live in tightly packed studio apartments or slum shanties with little air circulation, with most homes lacking toilets and running water. Because there is no trash collection and no proper drainage system, alleyways are lined with shallow pools of trash and sewage.

Less than a mile from Ms. Khatoon's government-built apartment lies the illegal shanty-town of Baba Nagar, where more than 50,000 people live amongst the mountains of waste in Mumbai’s landfills. During monsoon season from June to September, when Mumbai gets pounded by torrents of rain, living conditions become even worse. Medical professionals say it’s no surprise then that the area's slums and resettlement apartments boast the highest infant mortality rate in all of Mumbai, with 65 out of every 1,000 babies born dying within a month of their birth.

“In 2013, if we are still talking about malnutrition in this country, it is because the fundamentals have not been tackled,” says Kalpana Sharma, a veteran reporter of health issues in India. “The government schemes that are there are simply not enough to meet the need that we have.”

India as a model

Health officials say they will apply the lessons learned during India’s journey toward polio eradication to other health initiatives. A valuable byproduct of the country’s massive vaccination and monitoring effort has been the information network developed by India’s National Polio Surveillance Project and the WHO.

The surveillance system that oversees the millions of children vaccinated against polio each year is strictly monitored and provides real-time data for every case. Today, the number of children missed by vaccinators during the country’s annual national polio immunization drives is less than 1 percent.

During India’s last national "Polio Sunday" vaccination drive in February, some 2.5 million vaccinators were deployed across India to vaccinate 172 million children, with teams stationed first at booths and then traveling for five days around the country, administering vaccines door-to-door throughout city slums, housing projects, and rural villages. They even administered vaccines at bus stops, train stations, and cultural festivals, with intensified efforts in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which record some of the country’s highest birth rates and experience some of the highest rates of migration, according to data provided by Lokesh Gupta, Rotary’s PolioPlus Manager in India.

“When you have political commitment and government commitment: That spells success,” says Armida Fernandez of the Society for Nutrition, Education & Health Action, which works with residents in Dharavi, Mumbai’s largest slum. “The planning was excellent. Every single household, whether in registered slums or unregistered [illegal] slums … was counted.”

India will repeat the vaccination plan next year, with two nation-wide "Polio Sunday" campaigns planned for January and February of 2014 and three additional immunization drives in high risk states during the rest of the year, the WHO’s India Office said in a statement to The Christian Science Monitor.

Government ownership

India’s victory against polio has been contingent on strong political backing and the willingness of all players – whether central policymakers in New Delhi or private actors such as Rotary International – to monitor and push states forward as they implement the vaccination effort on the ground.

“Strong government ownership and accountability at all levels is crucial,” the WHO’s India Office tells The Monitor. “There has been a very high level of political involvement at the central level [with] regular feedback … provided to state governments.”

Systematized surveillance and state accountability will remain key, not only for maintaining health initiatives such as polio vaccination, but also for efforts to improve the country’s overburdened medical infrastructure as a whole.

“Health is essentially a state issue,” said John Townsend, director of the Population Council’s reproductive health program, at a videoconference with some of India’s top medical practitioners earlier this month. “While federal investments in health may be around 1.2 percent of GDP, states spend their money the way they want to.”

India’s 28 states and seven union territories each have a diverse range of health priorities. Facilitating communication and resolving disputes between policymakers at the central, state, and district levels will be key to administrating India's nationwide health plans, including polio vaccination.

“State governments used to be at constant loggerheads with the central government. A state can turn around and say ‘look, this isn’t my program: It’s a central [government] program',” says Kapur of Rotary International. “This is still a constant challenge."

* Roshanak Taghavi wrote this article as part of a fellowship with Johns Hopkins University's International Reporting Project. Follow Roshanak on Twitter at @RoshanakT.