Afghan TV show brings officials face-to-face with ordinary people

Loading...

| Kabul, Afghanistan

Afghanistan's imperfect democracy is finding one of its purest forms over the television airwaves, where ordinary citizens are getting a rare chance to question their highest officials face-to-face.

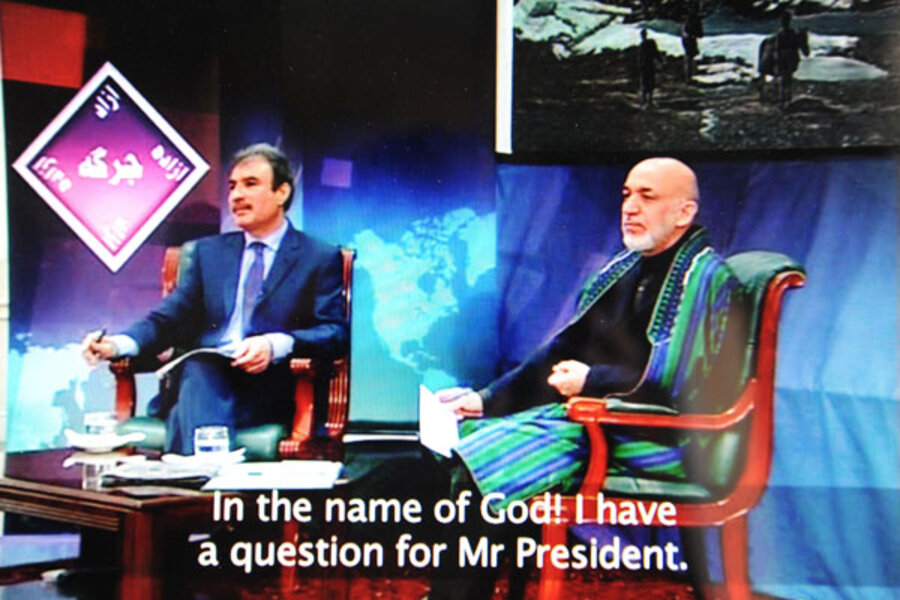

A debate program named "Open Jirga" is for the first time bringing a studio audience from every corner of the country to directly question the powers-that-be, from President Hamid Karzai and his ministers to the army chief. Rampant corruption, “wasted” years, and security fears of what will happen after US-led international forces drawdown in 2014 are all fair game.

A co-production of the BBC and state-run Radio Television Afghanistan (RTA), the program has given Afghans an unaccustomed taste of political accountability on a national stage.

“This is the kind of thing that shows democracy and freedom of expression, and people need to hear it,” says Zarghoona Salihi, a Kabul reporter for the Pajhwok Afghan News agency.

“Yes, there are different opinions among people,” says Ms. Salihi. “Some are shocked [at the access to authorities], some are tired of this system. Some people say it is useless and can’t change anything. Others say it is very good, and can cause many changes.”

In the nine episodes since December, officials sometimes appear as surprised as the audience, to be questioned by Afghans who are usually far from the nation’s security-bubble elite. Civil society activists, teachers, and lawyers rub elbows with farmers, cobblers, and butchers – with an average audience size of 70 – in feisty debates that are recorded and aired in both of Afghanistan’s two primary languages, Dari and Pashto.

“Ninety-percent [of the audience] are real people, a lot of them have never seen a provincial governor, let alone a minister,” says Shirazuddin Siddiqi, the BBC program’s country director and architect of Open Jirga.

“It’s been an amazing experience. I really don’t know if we will achieve the aim of contributing to building the future of Afghanistan, by people questioning their officials to bring some accountability,” says Mr. Siddiqi. But the events “especially bring minorities, women, the really aggrieved – especially people from remote areas and the provinces – to this national platform.”

The theme is based on the BBC show Question Time, which has been popular in the UK since the mid-1990s. The Afghan version resembles a similar, earlier project in Bangladesh. A couple of Afghan TV channels also run debate format shows, one that focuses on provincial issues, and another widely watched show called “Kabul Debate.”

“I didn’t get enthused by [the concept in Afghanistan] until I was convinced in 2010 that the whole decade of investment in blood and effort and goodwill was at stake,” says Siddiqi, of national rebuilding efforts after the US military forced the Taliban from power in late 2001. He says that millions poured into Afghan media development “left the provinces behind,” and that most media – because they choose to operate in either Dari or Pashto languages – were not inclusive.

“I had serious doubt [and thought] that Afghanistan’s politics were too fractured. And who can tolerate ordinary people putting their issues on the national agenda?” says Siddiqi. “My idea was to create a national dialogue and adopt the Afghan concept of jirga, opening it to educate everyone, so it naturally fit into Afghan culture.”

Karzai takes questions

The show is presented by Daud Junbish, a well-known Afghan BBC journalist. He twice interviewed the elusive Taliban leader Mullah Omar, who has been a fugitive since 2001. “Presenting” Open Jirga means only facilitating the conversation between Afghans and their authorities, under the gaze of five cameras. Mr. Junbish met with Karzai, who declared himself a “fan” of the show and agreed to appear in March.

The audience was not told until they were all within the palace gates that Karzai would be the one debating “governance.” That realization was greeted with surprise and nervousness.

“It’s important that ordinary people get a chance to visit high officials, and also a good opportunity for high officials who can’t normally see ordinary people,” said Laila Samani, director of a nongovernmental organization in the northwestern city of Herat, who was part of the Karzai audience in Kabul.

The first question came from a farmer from Wardak Province, who asked about Karzai’s performance over 11 years. Another man from Badghis Province said his elders had told the Afghan cabinet of their complaints for so long and with so little result “that hair has grown on their tongues.”

From ties to America to unfinished roads and lack of village drinking water, the questions came faster than Karzai could answer them.

Ms. Samani began with a proverb that “feeling sorry for a tiger with sharp teeth means being cruel to the sheep.” She then asked: “We see that individuals involved in … attacks are released several times.... Don’t you think it is a disloyalty to the Afghan people? Why is there no decisive treatment toward those arrested who have killed the Afghan people?”

The question was greeted with applause.

Another woman from the Panjshir Valley asked about the continuing insurgency: “You have called the Taliban brothers during 12 years … have you achieved a positive result?”

Karzai replied that seeking revenge in Afghanistan would not solve its problems, though it was “not forgivable” that Taliban continued to “kill our boys in Khost” and elsewhere.

“How much blood was shed in our country?” Karzai asked. “Is the solution in killing or is the solution in forgiveness, friendship, and forgetting? I have selected the path of forgiveness. The Talib who attacked me in Kandahar, I wish he was not killed. I would have forgiven him if he had survived.”

“I can’t begin to describe the emotions of people…. To see the power of questions asked to the president by genuine people,” says producer Siddiqi.

Ministers, MPs, and military leaders

Besides the president, Open Jirga has so far questioned 8 ministers, 7 parliamentarians, and top military and security officials. Prior to the debates, detailed research was done in seven provinces to determine issues that mattered most to Afghans by BBC Media Action, the BBC’s international development charity, with primary funding from the UK’s Department for International Development, along with EU and UN donors.

In a security debate that aired earlier this month, one audience member warned that Afghanistan could return to civil war after foreign troops largely depart in 2014 – a common lament of uncertainty about the future.

But Abdul Razaq Atif from Badghis suggested there was little reason for concern: “In the last 5,000 years of history our own people have ensured security, not foreigners.”

The commander of the Afghan National Army, Gen. Shir Mohammad Karimi, also sought to reassure fellow Afghans. He said Afghanistan’s “enemies” expected the army and police to “be defeated in one day,” after control has gradually passed from the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).

“But our operations in the last two months which dealt with direct enemy attacks proved our capability to our people,” said General Karimi.

“This is a very critical time in Afghanistan, and we are contributing to a critical debate. It has to have the ability to mobilize,” says Siddiqi, noting the uncommon “equality” that is evident – and praised by Afghans – on Open Jirga between citizens and their leaders. “The disillusionment is itself a challenge after 2014. This program is showing the potential of what a public broadcaster can do.”

* Follow Scott Peterson on Twitter at @peterson__scott