India's ban on BBC film boomerangs, as critics assail rape injustice

Loading...

| New Delhi

The Indian government’s ban of a documentary on rape has shone a spotlight on sexual violence against women at a time of a rising number of reported rapes but not a rising number of convictions.

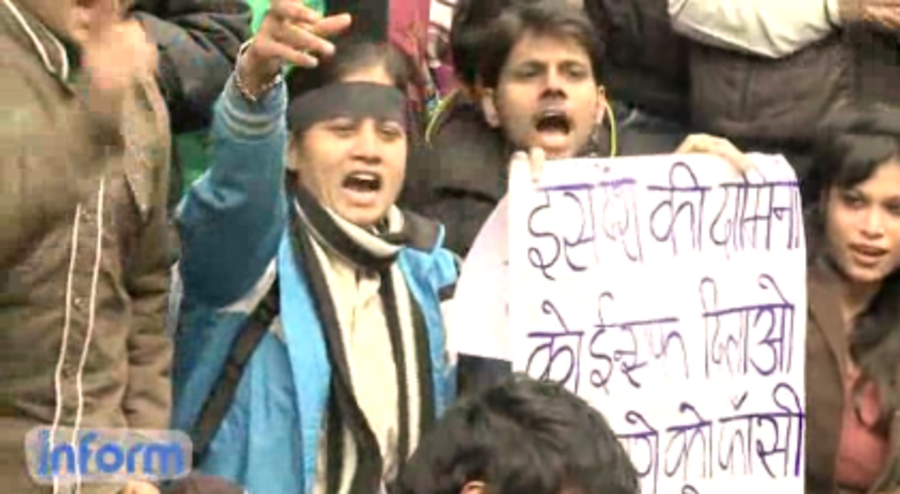

India is deeply divided over how to protect its women from violence. The debate got reignited by a new BBC film, “India’s Daughter,” on a notorious 2012 gang-rape and murder here of a medical student that sparked mass protests.

After the government banned the film, to the dismay of civil society activists, popular broadcaster NDTV aired an unprecedented hour of a blank screen, just as news broke that a violent mob had lynched an alleged rapist in northeastern Indian.

What the row over the film's ban has highlighted is that Indian women are increasingly reporting rape and sexual violence to authorities, and that India's justice system is slow and often inept at prosecuting these cases.

Accused out on the street

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, 93 women a day are raped in India. Yet in Indian courts, more than 90 percent of rape cases end in acquittal. Some 24,000 rape cases in India are languishing untried, with the accused mostly out on the street, experts say.

In Delhi the number of reported rapes has grown exponentially. In 2012, 585 cases were reported. By 2014, the number had grown to 2,069. In the first two months of this year, 300 cases of rape and 500 of molestation have been registered in India’s capital.

“High number of cases reflects that more women are coming forward to lodge complaints against sexual crimes,” says Delhi Police Commissioner B. S. Bassi.

Since the 2012 rape and murder of a young medical student, a case covered by the BBC documentary, police stations in Delhi have instituted 24/7 help desks for women, Mr. Bassi says.

Uber banned in Delhi

In Delhi, another high-profile case is that of Shiv Kumar Yadav, a driver who was working for Uber, a San Francisco-based online taxi service. Last December, Mr. Yadav, was charged with raping a young woman here. Later it emerged that Yadav had been arrested for rape in 2013 and was out on bail, which analysts say is a typical story. Delhi has since banned Uber from operating in the city.

In the climate of anger whipped up over the banned documentary, some regions of the country have reported mob violence. Last week, thousands stormed a prison in the state of Nagaland and dragged out a rape suspect, hauled him through the streets, and beat him to death.

The government's ban is ostensibly over sections of the film where one of the six rapists of the medical student gives his opinion about women. The rapist, Mukesh Singh, who is interviewed in jail, says in the film that “"a decent girl won't roam around at nine o'clock at night. A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy."

Lack of funds for women's shelters

The student and her boyfriend had mistakenly hopped onto a private bus at night with six men who were actually cruising the streets looking for a female to rape, it came out in the trial.

“There is no fear of law in India,” says Asha Rani, the late student's mother. “People commit heinous crimes and they boast about it.”

Critics say the government lacks clarity over how to combat violence against women and to deal with victims. India’s Women and Child Development Ministry had planned 660 centers around the country for safe shelter, legal advice, and counseling. But the plan has been suspended due to lack of funds and political will.

“Let us face it men in India do not respect women and any time there is a rape, blame is put on the woman that she was indecently dressed, she provoked the men," says Anu Aga, a social activist. “We need to change our thinking."