Letter from India: Lessons from an election with 900 million voters

Loading...

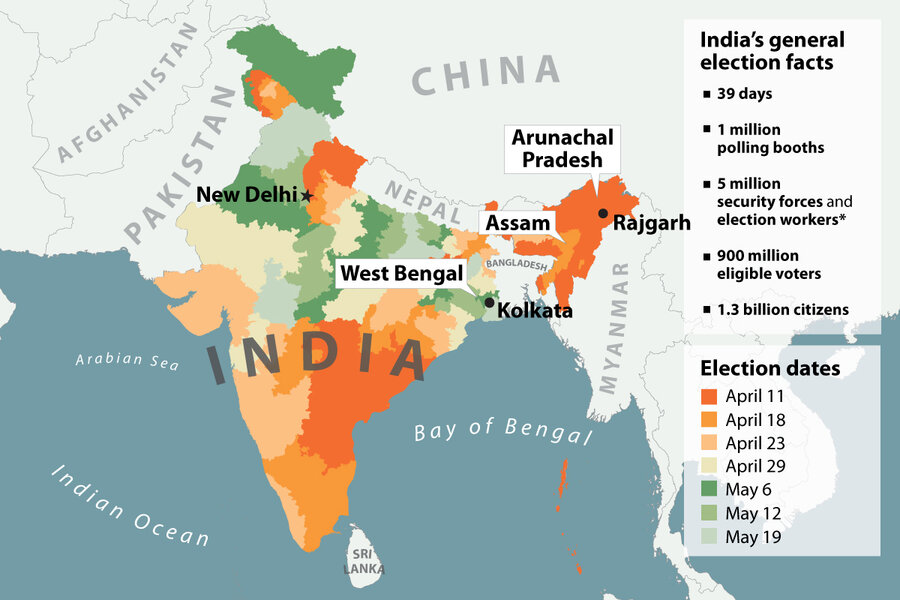

| Kolkata, West Bengal, India

When India’s elections, the largest democratic exercise in the world, kicked off April 11, reporter Sarita Santoshini was there to see it – there to vote, in fact.

In her home state of Assam in India’s far northeast, she and her parents drove to the school where voting machines had been set up (and, it turned out, frequently broke down), and she then waited her turn in a long line of women.

Why We Wrote This

Many fear that the rise of Hindu nationalism has tied ‘Indianness’ to religion. But being Indian also means taking part – not just on election days, but every day – in the largest democratic experiment on earth.

This Sunday, the last of the seven waves of voting found her in the city of Kolkata, where political tensions have sometimes flared into violence. As she walked from neighborhood to neighborhood taking in the on-edge atmosphere, she asked some of the country’s 900 million eligible voters what had brought them out to the polls amid the tension.

For some, it was jobs and the economy. But she also heard concerns about this staggeringly diverse country’s sense of unity. Many fear that polarization is on the rise and that animosity toward minorities is building – and finding sanction from politicians.

“I have been urging people to vote sensibly because I believe that democracy is at threat,” one voter told her in a largely Muslim neighborhood. “There have been clashes along religious and caste lines in the rest of the country. This was never the case in West Bengal. It’s slowly being provoked here as well, and we should stop that.”

It was a balmy April morning when I went with my parents to vote, driving to a high school at the end of a small town in Assam, my home state. My father had suggested that we cast our votes before noon to avoid any rush. But as we walked inside the gates at 11 a.m., the queues were already long. I soon learned, through chatter around us, that the voting machine had broken down three times that morning. Even as polling staff scrambled to get it fixed, voters had continued to patiently wait their turns.

Along with me in the women’s queue were young girls in salwar kameez and women in white-patterned mekhela chadors and brightly painted lips, exchanging greetings and asking each other about their journeys. Most had arrived here in Rajgarh the previous day, journeying by buses and trains from the towns where they now lived and worked. Two benches had been set on either side, where women took turns resting their tired feet. Each time a senior citizen joined the queue, there was a slight commotion as she was led to the front so she need not wait.

It was the first phase of the largest democratic exercise on earth: India’s general elections. It takes 39 days, about 1 million polling booths, and around 5 million security forces and election workers to reach the country’s nearly 900 million eligible voters. And this Thursday, it will all be over: India’s 1.3 billion citizens will learn if Prime Minister Narendra Modi has won a second term.

*Election Commission of India, Scroll.in

Why We Wrote This

Many fear that the rise of Hindu nationalism has tied ‘Indianness’ to religion. But being Indian also means taking part – not just on election days, but every day – in the largest democratic experiment on earth.

The Election Commission has gone to great lengths to try to ensure that no voter is left out. In the remote state of Arunachal Pradesh tucked at the border between China and Myanmar, one polling team’s journey included a helicopter ride and a daylong walk. Another team of six officers traveled for two days to a village near the Tibetan border, setting up a voting booth in a tin shed for a single voter.

But this general election, however grand, also carries with it the shadow of division.

Five years ago, Mr. Modi rode into office on promises of economic growth. But today, with the unemployment rate higher than it’s been in decades, many associate his administration more with Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, than creating jobs. To fans, it’s an overdue resurgence of national pride. To critics, it’s a dangerous turn toward polarization and conflict.

In Kolkata, where I now live, voters went to the polls on Sunday, May 19 – the very last wave. Curious, I walked down College Street, which had made news days before. Clashes between supporters of Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and West Bengal state’s ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) at Vidyasagar College had brought down a bust of the college’s namesake, an eminent Bengali scholar – one of several violent incidents in the lead-up to the vote.

As I approached the college’s polling site, a tense hush took hold. Large troops of security forces made regular check-ins. Inside neighborhood lanes, men gathered to quietly discuss their votes, while TMC workers around a table helped people find their names on the voter list and directed them to booths. Many voters condemned the violence and blamed it on the BJP, telling me they no longer trusted its promises of development.

Businessman Abhishek Agarwal, however, called the recent scuffles normal politics, irrelevant to his decision. In the BJP, he sees clear agendas and decision-making.

“The nation comes first. I have friends abroad, and they tell me that now we are being recognized as Indians,” he told me. “We are doing very well internationally under Modi.”

As the morning wore on, I left the subdued scene on College Street for the commotion of Sonagachi, Asia’s largest sex district – where police vehicles raced towards a tense scene between TMC and BJP workers and supporters – and hailed a taxi to Park Circus, a Muslim neighborhood. Roughly a quarter of West Bengal state’s residents are Muslim – a cause of frequent complaint for some Hindu residents, who say the number is growing and blame the TMC.

People arrived on bikes and rickshaws to cast their vote inside a school opposite a spacious field where kids played a game of cricket. Farmida Hussain, a housewife, sat under the shade of a tree to catch her breath. “It’s the time of roza [fasting, for Ramadan], so the walk here has made me a bit tired,” she said, wiping her face with a handkerchief.

Politicians are using religion to stir up supporters, Ms. Hussain said, but that shouldn't guide their votes. “When a school is built or a water tap set up, it does not selectively benefit a Hindu or a Muslim; it benefits everyone living there.”

“I have been urging people to vote sensibly because I believe that democracy is at threat,” voter Shahnawaz Khan told me as he waited for his wife to finish her ballot. “There have been clashes along religious and caste lines in the rest of the country. This was never the case in West Bengal. It’s slowly being provoked here as well, and we should stop that.” Of all the hate crimes committed between 2009 and 2019, 91% took place after May 2014 – the month Mr. Modi’s administration began – according to the Hate Crime Watch database. Most targeted minorities, especially Muslims.

Driving back through the near-empty city, I looked at the faint spot of black ink still visible on the nail of my left index finger – a reminder of my own voting experience in Assam.

Inside the school, officers admitted two voters at a time, checking IDs and looking for names in their thick stacks of paper. My index finger was marked with indelible black ink, my signature recorded in a register, and off I was sent to the electronic voting machine, with a button against the name and party symbol of each candidate.

Filled with both hope and dread, I took a deep breath and pushed. A beep confirmed my vote, and for a few seconds, a slip with my chosen party’s symbol appeared behind the glass, then slid into a locked box.

I walked out silently. It was hard to shake off the heavy weight of responsibility.

“I live in India, so it is my duty to come out and vote no matter what,” embroidery worker Sheikh Abdul Kalam told me Sunday as he waited outside a polling booth. “This is my identity. I can’t give it up.”