In Philippines, a push to preserve accounts of life under martial law

| Manila

Edita Burgos remembers the Philippines’ martial law period as a time when people were afraid they’d be tortured or killed for speaking against the Marcos regime. As the general manager of political newspaper WE Forum, she saw her offices raided and colleagues arrested before Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s ousting in 1981.

In recent decades, she’s also witnessed the Marcos family’s unrelenting historical denialism, culminating in the presidential campaign of the dictator’s son, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., earlier this year.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn a country where misinformation is rampant, how are truth-telling citizens working to turn the tide? After the election victory of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in the Philippines, many are rushing to safeguard archives and promote public history.

Now in office, the junior Mr. Marcos continues to harness social media to spread misinformation about his family’s legacy and ongoing court battles. The family’s success has been a wake-up call for many Filipinos, who are rushing to protect and promote firsthand accounts of martial law. Some have started digitizing 1970s archives, while others search for ways to bring survivors’ stories to new audiences.

Mrs. Burgos says saving history from distortion “is the job of honest people,” and that new initiatives aimed at defending truth “give us – the older people who live through martial law – encouragement and hope that the dark days will never be forgotten.”

“However ... we haven’t even scratched the surface,” she adds. “We only reach progressive thinkers and those who understand the importance of history.”

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. insists that his father was not a dictator.

To hear him tell it, the elder Marcos – who is believed to have stolen $10 billion from the Philippines before his ousting in 1986 – was a hardworking and collaborative leader who was forced to declare a nine-year martial law to protect his country from the overwhelming threat of communism. His only fault, his son and namesake recently told an interviewer, was that he cared too much about Filipinos.

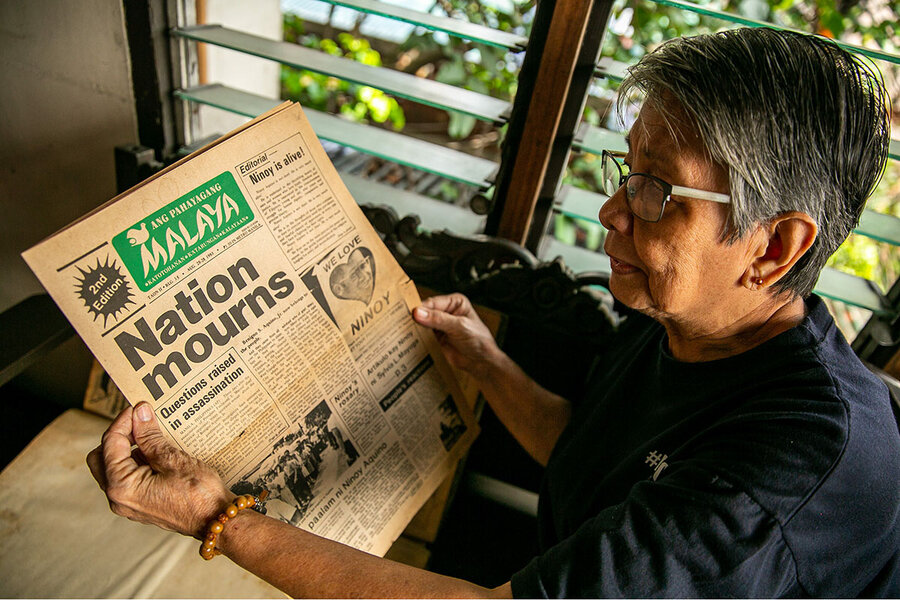

Edita Burgos remembers the Marcos period differently. Widow of famed press-freedom advocate Jose “Joe” Burgos and former general manager of political newspaper WE Forum, Mrs. Burgos recalls how the elder Mr. Marcos ordered the arrest of hundreds of government critics, including opposition leaders, journalists, and student activists. She remembers her office being raided in December 1982, and her husband detained, for publishing an investigation into the dictator’s dubious war medals. This was a time, she says, when people were afraid to leave their homes, scared they’d be tortured or killed for speaking against the Marcos regime.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn a country where misinformation is rampant, how are truth-telling citizens working to turn the tide? After the election victory of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in the Philippines, many are rushing to safeguard archives and promote public history.

She’s also witnessed an unrelenting campaign of historical denialism and distortion that began after the return of the Marcos family from exile in the early 1990s, and how the presidential campaign of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. exacerbated the trend.

Now in office, Mr. Marcos continues to harness social media to spread misinformation about his family’s legacy and ongoing court battles. But the family’s success has also been a wake-up call for many Filipinos, who are rushing to protect and promote firsthand accounts of the martial law period. Some have started digitizing 1970s archives, while others search for ways to bring honest accounts of martial law to new audiences.

“Disinformation has been happening even before the victory of Marcos Jr. and the problem is we started too late in responding to it,” says political analyst Antonio La Viña, who heads a broad coalition of lawyers, academics, and nongovernmental organizations known as the Movement Against Disinformation.

“We should have done this three or four years ago, but it’s not yet the end of the battle,” he says.

Protecting the archives

In the weeks following the May 9 election, Reuters reported that books about the elder Mr. Marcos were “flying off the shelves.” Historian Francis Gealogo of the Ateneo de Manila University says that “only shows that Filipinos know the value of honest accounts about the past.”

But like many who voted against Mr. Marcos in this year’s election, Karl Patrick Suyat worries those honest accounts are now under threat.

The University of the Philippines student believes the Marcos family has every reason to target evidence of their patriarch’s decades in power, especially the martial law years. Indeed, since the junior Mr. Marcos took office, proposed budget cuts to the National Archives, the National Historical Commission, and other agencies tasked with protecting Philippine history have sparked backlash from lawmakers.

So Mr. Suyat started Project Gunita, a digital repository of dozens of books, magazines, and newspaper clippings that shine light on the political, economic, and social injustices during the martial law era. Human rights organizations reported at least 3,257 people were killed during the Marcos military rule, while some 34,000 individuals were tortured and 1,600 were victims of enforced disappearances.

“These materials do not lie. These are the most honest accounts about martial law and the abuses,” says Mr. Suyat.

The Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Monument of Heroes) Foundation – which aims to preserve not only “the horrors of martial law under the Marcos dictatorship but also … the bravery, courage, sacrifices, and the lives of those who fought for freedom,” according to executive director May Rodriguez – also started digitizing its collection earlier this year.

However, as both amateur historians and major cultural institutions have learned, making archival materials available online is not enough to combat misinformation.

“We haven’t even scratched the surface”

Mrs. Burgos says saving history from distortion “is the job of honest people,” and that new initiatives aimed at defending truth “give us – the older people who live through martial law – encouragement and hope that the dark days will never be forgotten.”

“However, as a nation of democracy defenders, we haven’t even scratched the surface,” she adds. “We only reach progressive thinkers and those who understand the importance of history.”

She donated copies of every issue of WE Forum and the Burgos’ other major publication, Pahayagang Malaya (Free Newspaper), to the Ateneo Library in Quezon City, but it hasn’t made a huge difference, she says.

“People do not know how to access them or they don’t know that a digital copy exists,” she says.

Veteran journalist Inday Espina-Varona agrees. Archival work is “not enough if the truth will just sit” in a huge library or online database, she says.

“We must learn to make truth our weapon,” says Mrs. Espina-Varona, who was the former head of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines and has been a victim of vilification and misinformation online. “We must learn to get it, use it, and translate it into action.”

Bringing the past to the people

The Monument of Heroes Foundation is trying to do just that. While their digital archiving project is underway, Ms. Rodriguez says “our main weapon against historical distortion is the museum.”

The foundation is experimenting with new ways of getting people to visit their site, which includes a Wall of Remembrance featuring the names of 320 martial law martyrs. They recently organized a series of activities to bring people to the museum, including a clean-up drive that involved youth and environmental organizations.

Mr. Gealogo, the historian from Ateneo de Manila University and a former commissioner of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, in August led the relaunch of Tanggol Kasaysayan (Defend History), a group first established in 2016 with the goal of helping history professors and teachers combat misinformation about the Marcos family. In this new phase, Mr. Gealogo hopes to broaden the group’s reach, to rally “not only those who teach history,” but “people in all sectors who want to defend democracy and the truth.”

They’ve started forming local chapters, tasked with promoting discussions on Philippine history in schools, communities, and workplaces. In October, Tanggol Kasaysayan released a book titled “Martial Law @50: Memory and History of Refusal.” It offers a collection of extensively researched essays to aid the public in learning about one of the darkest periods in Philippine history.

While protecting and promoting existing records of martial law is critical, Mr. Gealogo also calls on survivors or any Filipino with insight into this period to create new knowledge by recording their stories.

“We must do everything to fight any attempt to erase history,” he says.