Author of mafia exposé lives in spotlight – and gun sights

Loading...

| London

The first people Roberto Saviano sees every morning are his bodyguards – the three Italian policemen who pick him up in a bulletproof sedan, drive him to the gym, or take him on errands. They haven't left him alone since "Gomorrah" – his fierce critique of the Neapolitan mafia, the Camorra – hit best-seller lists in October 2006, bringing fame, fortune, and some powerful and ruthless enemies.

But today, because of international and British laws that don't permit him the usual retinue of government bodyguards here in London, he's been entrusted to me – 135 pounds of journalistic muscle. Mr. Saviano doesn't speak English, and I – a native Neapolitan, myself – do; so his agent thinks I'm some sort of protection for him, and I laugh half-heartedly when the agent jokes about me being his bodyguard for a day.

I accept the task as coolly as I can, but in the back of my mind I'm wondering if I might end up between him and a hit man. I'm hardly relieved when, cautious but confident, Saviano walks out of his hotel wearing a dark coat, unmissable Italian sunglasses, and a dark scarf pulled up to his wool coppola cap. Nor am I comforted when the taxi driver, who seems to have been instructed not to breathe the name Saviano, calls out "Car for Mr. Roberto."

But as he cheerfully sidles into the back with me, it's his sunny disposition in spite of it all that cuts the tension. He peels off his hat and glasses and jokes about how conspicuous he looks wearing them in London.

This is our second day together, and maybe having a fellow Neapolitan interviewing him puts him at ease, but he chats freely as if we were old schoolmates with catching-up to do.

Saviano seems refreshingly laid back and down-to-earth for a 28-year-old who's sold over a million copies of his book in Italy alone, has been published in 33 other countries, is the only Italian on the New York Times and Economist Best of 2007 book lists, and, more important, for someone whose life is under constant threat.

And he isn't scared, either.

"They'd never kill me here in the UK," he says. Also, he's in the spotlight now and it wouldn't be the right moment for the Camorra to kill him, he seems to think.

It turns out I was more worried than he ever was.

• • •

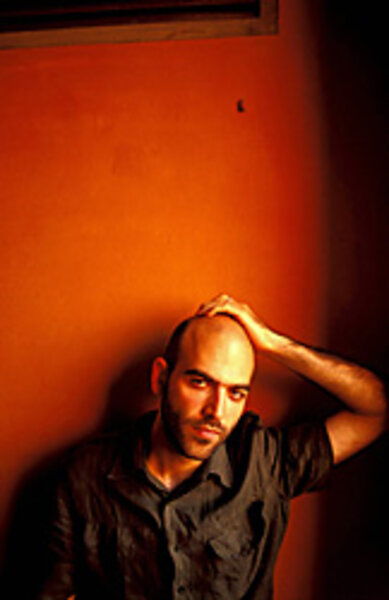

Despite the publicity shots that always portray him as serious and pensive, Saviano actually laughs a lot, especially about himself and his Mafioso looks: "If I didn't look like a proper Camorrista, the book would have never done this well."

He's right, at least about his appearance. He has the dark Mediterranean look, is short (just 5' 5"), slim but moderately well-built. He doesn't have much hair, but his huge brown eyes sparkle. With the coppola cap and the sunglasses, he looks like any dodgy guy back home. And he can talk like one too, though mostly he speaks a clear and clean Italian with a Neapolitan twang.

But it's not only the looks and vocabulary that Saviano shares with the subjects of "Gomorrah." Raised in Casal di Principe, a town of 20,000 north of Naples, home to a powerful Camorra clan, Saviano stumbled across his first murdered body as a teen on his way to school. It's in the same town that he learned about the power of affiliation and belonging – when he'd ride his bike to nearby towns with his friends and scare other kids away by simply saying, "I'm from Casale."

"Corleone for people in my town is like Disneyland," he says, comparing the Sicilian Cosa Nostra town of "The Godfather" with the less publicized but more thriving towns of southern Italy's Camorra. "I grew up in a cutthroat reality."

Saviano's personal accounts, police reports, and trial evidence make "Gomorrah" an unprecedented description of that reality. It tells how the System (the name Camorristi use to refer to themselves) profits from drug trafficking, clothes manufacture, waste disposal, and public work contracts and feeds off the endemic problems of Naples – youth unemployment (40 percent), waste management crises, and political corruption.

Until the book came out in 2006, Camorra stories had only been the subject of local news reports, not international bestsellers. Saviano never trained as a journalist – he thinks of himself more as a writer. He graduated in philosophy and then did some work for national newspapers. But how did he go from the boy on the bike proud of Casale's reputation to the young writer confined to a bulletproof sedan?

"I often say that fortunately, or unfortunately, I am made of the same clay as the people I write about. I don't feel a difference in our formation, but in our choices," he says.

His father was a local doctor who was always a bit envious of the Camorra's power and money and taught Saviano how to shoot a gun when he was young. But when he saved the young target of a shooting – instead of leaving him to die as mafia doctors are supposed to do – he was beaten up for it. Saviano's mother, on the other hand, was a teacher from northern Italy, who gave him the cultural instruments to distance himself from his surroundings.

Above all, however, it was his desire to understand how the System worked that pushed him to go down a different path. "I didn't choose a different path because I thought that what they do is morally revolting," he says. "What I'm trying to do is to understand where their world begins and the legal world ends, and I've understood that they often coincide."

He uses the example of a neighbor, a boss who'd invited Saviano to his daughter's wedding and who'd paid for another neighbor's studies abroad. "It's hard to think that that same clever, generous, and kind man could one day kill a guy ... by making him swallow sand just because he'd been flirting with his niece."

Saviano is a traditionalist in many ways, like many in our corner of southern Italy. In the custom of Casal di Principe, his town, he wears three simple rings on three separate fingers – they look like wedding rings and signify the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. He is not a churchgoer, but he is not an atheist either. In fact one of the people who most inspired him was Father Peppino Diana, the antimafia parish priest of Casal di Principe who was murdered in his own church in 1994. (Father Diana compared Casale and its surroundings to the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, destroyed by God for the sins of their citizens. That's where the wordplay used in the book title comes from.)

But ultimately it is Saviano's questioning of what drives people's decisions and what makes people tick that sets him apart from the rest.

"Understanding was my real vaccination, not rebelling against their violence," he says. "My fascination with that world remains, and I know it's dangerous, but I have written a book to try to take it apart."

And that book has cost him a lot. When it came out, even his friends and family left him alone. People in Casale thought he was a betrayer trying to profit from his experiences, and his family simply couldn't understand why he'd write about something as awful as the Camorra.

And then came the threats – that he believes are from the bosses he named in the book and who are suing him for libel. (He says he still can't forgive himself for putting his family in danger, too.) But worst of all, he says, was the police protection.

"Since I started living under escort, I've been feeling like a half man," he says. "People in Casale say that [the Camorra has] built me a coffin without having to shoot me in the head."

• • •

We'd spent our first day together at Oxford University, where a bunch of Italian students who came to hear him talk were fascinated by him. He relaxed and joked with them about how bad English food is and how hard it must be to live away from home.

Seeing what a following he had here – and all over the world (his recently formed Facebook group has 1,200 members and there are over 6,000 on his MySpace profile) – it was hard to believe how lonely he must be at times. (His family has given him full support since he started receiving threats, but he's not in touch anymore with most of his old friends.)

So, wouldn't he rather leave and go somewhere where he didn't need constant police protection?

"Of course," he says. "But I can't do it yet. I've become a symbol and if I left I'd be giving in to their power. I need to keep going for now, and then we'll see."