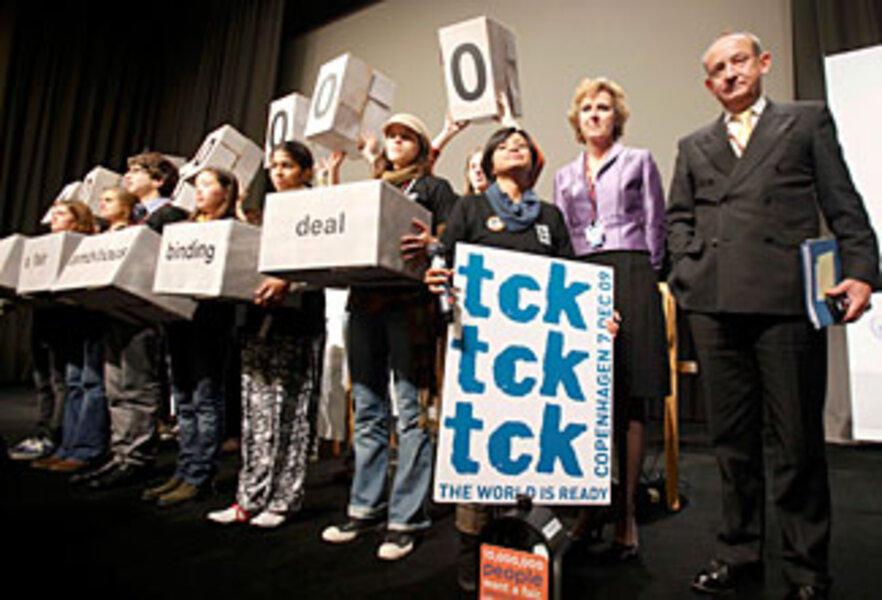

Clock ticking as Copenhagen global climate change summit begins

Loading...

| Copenhagen

Delegates from more than 190 countries today opened what some are calling a historic round of talks on climate change in Copenhagen. But the final chapters remain to be written.

Not since the 1997 negotiations in Kyoto, Japan have talks on global warming attracted such high-level political involvement. Leaders from some 110 countries, including President Obama, are slated to appear at the end of the conference to help give the meeting a push toward what lead US negotiator Jonathan Pershing calls "a comprehensive, operational Copenhagen accord."

"This conference has already written history," said Yvo de Boer, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change's executive secretary, arguing that delegates' opening statements indicated that countries "want to deliver a strong ambitious outcome in Copenhagen. This conference will write history. But we need to make sure it writes the right history."

The effort will not be easy, Dr. Pershing added. "There is much work to be done."

Negotiators are working on two deals, running on parallel tracks. One involves a new commitment period for the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, under which industrial countries that ratified the agreement initially promised to reduce their collective greenhouse-gas emissions to 5.5 percent below 1990 levels by 2012, a target they are still hoping to meet. A second commitment period to meet this goal is being discussed by the countries that ratified the protocol. The second, higher-profile track is an agreement that would cover the US – which did not ratify Kyoto – and developing countries, perhaps to be dubbed the Copenhagen Protocol.

The aim is to reach political agreements here that can lead to immediate action on greenhouse-gas emissions control and provide a quick influx of cash to developing countries to help them adapt to climate change and pay for the technologies that could help them leap-frog energy technologies that spew carbon dioxide.

Expensive proposal

The sums being considered are large: $10 billion a year between 2010 and 2012, then upwards of $100 billion a year out to 2020.

Legally, the boundary between the two is clear. In negotiations, the boundary is blurred. Developed countries are reluctant to further tighten the screws on their emissions unless major developing countries, whose emissions are climbing, come forward with significant emissions-control offers. Developing countries are loathe to take action under an international agreement unless developed countries offer aggressive emissions-reduction plans. This is especially true for the US, which gave the world eight years of what was widely perceived as inaction on the issue.

Poorer nations also complain they're being asked to adopt expensive solutions that will slow economic growth, while economic powers like Japan and the US have already enjoyed the fruits of pumping lots of carbon dioxide (CO2), the principal greenhouse gas. A joint study by the World Wildlife Fund and the climate research unit of German insurer Allianz found that the US pumps the equivalent of 25 tons of CO2 per person a year. China, by contrast, pumps five.

With the US now fully engaged in the talks, the dynamics are beginning to shift, says Heather Conley, who heads the Europe program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

When the US was engaged in the Kyoto process, it and countries such as Japan, Canada, and Australia tended to line up against Europe as negotiators tried to hammer out rules for implementing the agreement. Since the Bush administration pulled the US out of the Kyoto process in 2001, Europe has been the driving force among industrial countries in efforts to move beyond Kyoto.

Global warming "has been their number-one priority," Ms. Conley says. The Europeans were the first to set out 2020 emissions targets, then added the proviso that if other industrial countries followed suit with aggressive targets for 2020, they'd tighten their emissions reductions further. They offered up the first outlines of a financial-aid package for developing countries. And in early visits with President Obama, European leaders jawboned the president on the need for aggressive US emissions reductions.

"They really thought the process would achieve a legally binding treaty in Copenhagen," she says. Instead, officials now talk of reaching a political agreement here regarding efforts by the US and developing countries, and leaving negotiators to work out language and operations details for a legally binding agreement next year.

Eyes on US and China

All eyes are now on China and the US, which combine for 50 percent of the world's greenhouse-gas emissions.

During a briefing Monday Andreas Carlgren, who heads the European Union's delegation, said the EU hasn't seen offers from other countries sufficient to trigger the additional cuts Europe has pledged. The endgame, he said, "will be mostly about what will be delivered form the United States and from China."

Their bids to date are historic, he says. But they fail to reduce emissions enough to put the planet on a path to holding global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), a goal that has broad agreement among international negotiators.

For its part, the US is taking a significant step, counters Dr. Pershing. Obama offered reductions for 2020, subject to congressional action on energy and climate bills. Obama's offer also outlines additional cuts and deadlines through 2050. At that time US emissions reductions would be in line with what scientists say is needed to close in on the 2-degree goal.

Still, Mr. de Boer says that China's offer accounts for some 25 percent of the emissions reductions needed to avoid a 2-degree temperature increases.

Given the political strictures on Obama – he can't promise anything beyond what he might reasonably expect Congress to support – these talks may turn out to be an exercise in managing disappointment for the EU, Conley says.