As Barcelona bans bullfights, reeling Spain seeks its national soul

Loading...

| Barcelona, Spain

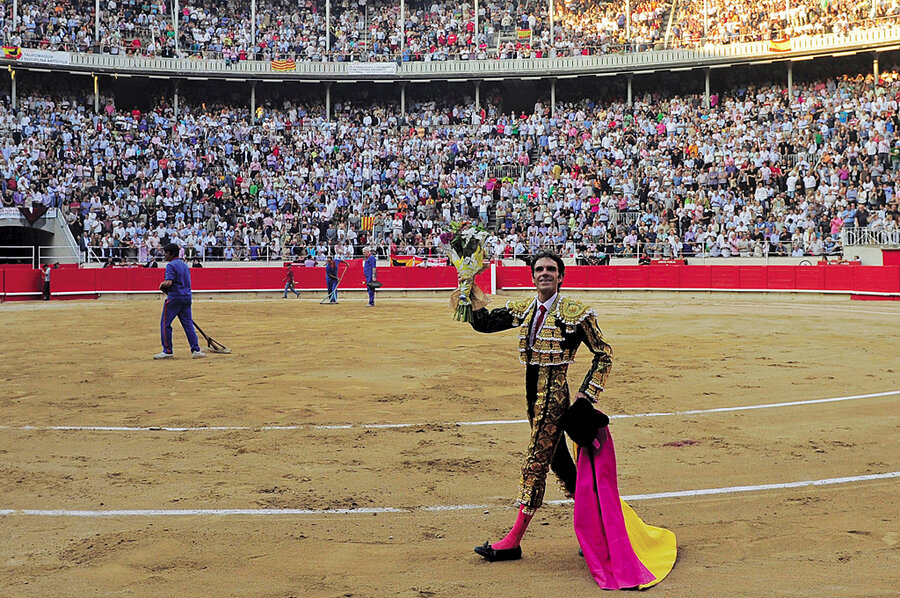

As Barcelona's final bullfight ended on Sept. 25 to a house ovation, the festive crowd poured out of the Monumental Plaza bullring carrying the matador on their shoulders. Euphoric shouts of "Olé!" and "Torero!" filled the air as these fans bid farewell to Spain's iconic pastime, which won't be allowed in this region after a 2012 ban goes into effect.

For Manuela Delgado, a housewife who traveled across the country with her husband to witness the historic finale to centuries of Spanish bullfighting in this autonomous region of Catalonia, the event struck at the heart of the national psyche. "Catalonians are taking away the bulls, something that belongs to all of Spain," she said.

Her grievances were not an issue of nationalism or animal rights. Instead, they echoed a more profound sense of confusion that has swept Spain's young democracy. Over the past decade, the country has careened from boom times to bad times, becoming a key liability in Europe's debt crisis. Now, as it comes to terms with a Nov. 20 election that turned the political map on its head with the election of a conservative prime minister, the question for many here is what kind of Spain will emerge.

Across the political spectrum, people are scrutinizing the country's very identity. Ms. Delgado was inspired to act when a cultural institution she cherished was threatened. Others are unnerved by the growing popularity of regional pro-independence parties. Polls indicate that the majority of people under age 35 feel detached from leaders.

The conservative Popular Party unseated the Socialist Party and will hold an absolute majority in parliament. With 72 percent voter turnout, conservatives got nearly the same number of votes as in 2008. Socialists lost 35 percent of their votes, which went to parties in the center and the more radical left.

Franco repressed regional identities

Dozens of interviews across the country paint a picture of uncertainty and discontent. "Something broke in Spain," says taxi driver Francisco Fernandez. Mr. Fernandez says Spaniards have no choice but to bring leaders "down from the clouds."

Spain's modern democracy started with the 1975 death of Gen. Francisco Franco. The fascist dictator came to power after the Spanish Civil War in 1939 and brutally repressed civil rights and regional identities to keep the country unified. Mistrust crossed all lines, political and regional, as a result.

After Franco's death, nation building was a priority. Spaniards agreed to put off sensitive issues like federalism and national symbols to let democracy transition naturally in a country with four official languages and many distinct cultures. To this day, Spain's national anthem lacks lyrics.

Spain's experiment with democracy nearly collapsed in 1983 with a failed military coup, but all worked more or less smoothly starting in 1986, when Spain entered the European Union.

Economic growth was strong at first, fueled by EU funding and then by a booming construction sector. Not even recurrent terrorist attacks from Basque separatists and Islamist radicals – including the 2004 Al Qaeda-inspired Madrid train bombing that killed nearly 200 people – derailed a confident Spain. Priorities changed: Spain built an expansive welfare system, and the government borrowed cheaply and invested in infrastructure, education, health, salaries, and pensions.

But the global economic crisis that began in 2008 dragged Spain into an unprecedented recession, and political and societal turmoil followed. Spain is probably heading for its second recession in four years, and growth is expected to remain elusive for at least another two years. The country faces an overwhelming 21 percent unemployment rate coupled with decreased public spending.

As its economic system overheated and the safety net eroded, old grievances that were put aside after Franco's death resurfaced.

"Expectations were high [after the dictatorship ended]," says José García Montalvo, an economics professor at Barcelona's Universidad Pompeu Fabra. Spain may be out of its democratic infancy, but it still faces many hurdles, Mr. Montalvo says. "You have to accept many things. But in our case, [growing pains] coincided with the economic crisis, which made it more painful."

The economy is the top worry for most Spaniards, followed closely by concern over the country's political leadership. This political concern ranked higher than housing, health care, and education combined, according to the most recent national poll by the government's autonomous polling institution.

This profound doubt about the system's ability to fix itself is a paradox, says Félix Ortega, a sociology professor at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and an expert in the public sphere. "The fundamental problem is that people don't believe in democratic institutions," Professor Ortega says.

'Historic polarization' must end

The most incredulous by far are those under 35, Spain's "lost generation." "It's as if for years of democratic transition politicians have been polarizing us between left and right, or Catalonian and Madrilenean," says Pedro Acosta, a young communications freelancer active in Madrid's 15-M movement, a precursor to America's "Occupy Wall Street" protests. "Now we know it's not true and that we have to fight to resolve our real problems."

Spain's next prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, has already spoken of the need for greater social unity. In early November, for example, he said he wanted to persuade Catalonian authorities to repeal the ban on bullfighting, in the name of a unified Spain.

"The bullfighting issue is not about taste ... but about a pillar of Spanish identity," says Fermín Bouza, an expert in mass movements at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. He says the divisive reaction to the end of bullfighting in the Catalan region highlights a basic problem. "Spain's historic polarization is still there and a lot of people still don't accept the dynamics of democracy."