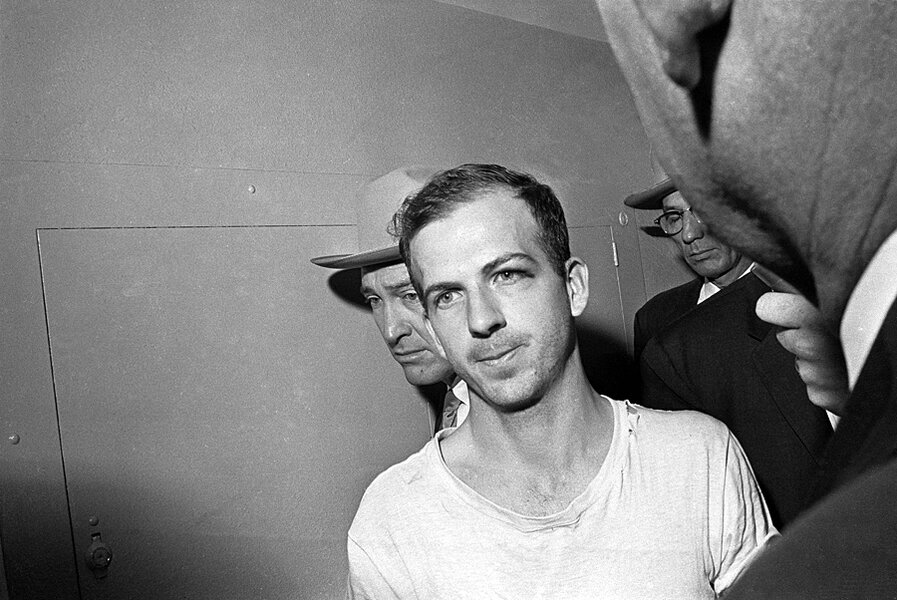

Why Soviets were no fans of Lee Harvey Oswald

Loading...

| Moscow and Boston

Lee Harvey Oswald’s Russian was still shaky in 1961, when he was working as a factory metalworker in the provincial Soviet city of Minsk. It fell to a young student engineer named Stanislav Shushkevich to help him out.

"He was a simple martinet, and I found nothing in common with him. His Russian at that point was passable. We had about a dozen lessons in all, after that we had no contacts,” Mr. Shushkevich told the Monitor in an interview. “My main concern later on was that he would be given the task of fabricating equipment I had designed, because he was such a terrible metalworker.

"When I learned later on about Kennedy's murder, and that Oswald was involved, I was thunderstruck. I even wondered ‘How could I have lost interest in this person? Maybe I don't understand people at all?’ " said Shushkevich, who later became the first president of independent Belarus.

As the US revisits that breathtaking moment on Nov. 22, 1963, attention is again turning to Oswald’s time in the Soviet Union – a 30-month period that ended a year before President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, a journey that left him with a Russian wife but disillusioned about socialism.

Although any evidence of panic in the Kremlin remains buried in classified Politburo archives, historians say there seems little doubt that Soviet leaders must have scrambled for explanations after Oswald was named as Kennedy's killer.

“The Kennedy assassination struck like a bolt from the blue, it shook up both sides,” says Valery Garbuzov, deputy director of the official Institute of USA-Canada Studies in Moscow. “We felt more than regret. We began a long process of dialogue, meetings, and negotiations. Things were not the same after that.”

According to historians of the period and to people who knew him during his time in the Soviet Union, Oswald was considered an insignificant fish when he arrived in in October 1959, declared himself to be a communist, and begged to be granted Soviet citizenship. At first, Soviet authorities refused his request, but later relented when he injured himself, making travel back to the US impossible. He was eventually sent to Minsk, then a provincial Soviet backwater city that is now capital of independent Belarus.

“They gave him a document as if he had no nationality, did not let him remain in Moscow, but sent him to Minsk. He was given a flat, and a job, but was under control of the special services," the whole time, says Oleg Nechiporenko, a former KGB colonel, who later interviewed Oswald at the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City.

At the Gorizont Electronics Factory in Minsk, Shushkevich was a student engineer who often translated English-language technical articles, and he was assigned in early 1961 to tutor the new American worker.

"I was not a party member, but one day the plant party secretary came to me and said I was to be given this big honor, a commission from the party, to teach Oswald Russian. I was not allowed to ask him about his past, who he was or anything like that. And we were never left alone, there was always another English-speaking person present," Shushkevich remembers.

Oswald apparently grew bored with life in Minsk, which was considered dull even by Soviet standards. Even though Soviet authorities had given him a good apartment and high salary by Soviet standards, he grew disillusioned with the regimentation of Soviet life, the forced "voluntary" work on weekends, and the lack of things to buy in Minsk shops.

In mid-1962 he applied for permission to return to the US, along with his new Russian wife, Marina Prusakova, and Soviet authorities appear to have had no qualms about letting him go.

It was Oswald's unexpected visits to the Cuban and Soviet embassies in Mexico in September 1963 that may have later looked suspicious to US investigators. Mr. Nechiporenko, the main KGB officer who dealt with him, says Oswald wanted a visa to return to the Soviet Union, but the Russians had little interest in taking him back.

"He was in a hurry to get what he wanted. I told him we weren't authorized to give visas to citizens of third countries. He said he'd already appealed to the Soviet embassy in Washington, but didn't get an answer from them.. . . I explained that if we sent a request to Moscow to make an exception for him, that could take three or four months. He replied that was unacceptable, that his life was at stake," Nechiporenko recalls about the embassy meeting.

Oswald returned to the Soviet Embassy the next day with a pistol, Nechiporenko recounts, saying that he was being persecuted by the FBI.

"He took out his pistol.. . . He went on saying he has to go around armed, and that if he faces danger he may have to use his weapon. He didn't say against whom he might use his gun, he didn't mention any names," he adds.

Nechiporenko says he reported to Moscow about Oswald's two visits, but heard nothing back until after the Kennedy slaying. When journalists came to Mexico to ask about Oswald, embassy staff had no instructions about what to tell them so they kept silence, he says.

"I know there are supporters of conspiracy theories, but I believe Oswald was a lone killer," adds Nechiporenko, who has written a book about his experiences.

Khrushchev's son remembers

Sergei Khrushchev, son of Nikita Khrushchev, who led the Soviet Union at the time of the Kennedy assassination, says there was genuine shock in the Kremlin when news of the assassination broke, and worry that the Americans would immediately blame Moscow.

“My father was concerned about this, and he called to the head of the KGB, Semichastny, asked him to prepare all the papers about Oswald, and Semichastny reported to him that the Soviet Union and KGB had nothing with Oswald,” Khrushchev tells the Monitor in an interview. “They did not work with him during his time in the Soviet Union, because they found him useless, and through this they of course could control him but they did nothing. And after this, they have no more contact with him.

“My father told him to prepare this document and present them to the Americans to help them with their investigation and not to lead them in the wrong direction that the Soviet Union could be involved in this,” says Khrushchev, who emigrated to the US in 1991 and who now lives in Rhode Island.

Declassified FBI files released in the 1990s discuss how Anastas Mikoyan, Khrushchev’s top deputy who led the official Soviet delegation to Kennedy's funeral, approached Jacqueline Kennedy in Washington to give her condolences.

Roy Medvedev, a former dissident and one of Russia's leading historians, says that meeting was Mr. Mikoyan’s own doing, without special instructions from Moscow. Khrushchev disagrees, saying his father was very involved in the discussion, overruling the suggestion by then-Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko that the Soviet ambassador to the US should attend.

“My father said ‘No, it cannot be the ambassador as usual, in this special case we have to send someone at a much higher level.’ My father thought about going himself, but then he thought ‘No, no, maybe it would be not good for both sides,’ so he thought let’s send my first deputy, Mikoyan, who was a great diplomat,” Khrushchev says. “So he was went there under my father’s proposal and the Presidium’s Central Committee… and he was authorized to make all these steps, including meeting with Jacqueline Kennedy.”

Kennedy's death came near the end of the period known as the "Khrushchev Thaw," a heady time for young Soviets in which tough party control over intellectual life was relieved and the crimes of the earlier Stalin period were aired publicly. By late 1963, however, Mr. Khrushchev's reforms were already petering out under fire from hardliners, who removed him from office in an inner-party coup a year later.

The scare over Oswald, coming so soon over the Cuban Missile Crisis, may also have convinced Soviet leaders that they needed more reliable channels of communication with Washington, and helped to usher in the period of détente in the next decade, says Mr. Garbuzov, deputy director of the official Institute of USA-Canada Studies in Moscow.

"Kennedy was handsome, clever, charming, and he had made a strong impression. We knew nothing of his shortcomings at that time,” Mr. Medvedev says. “I recall one functionary of the Communist Party's central committee coming over after the assassination to say ‘he was just too good for this world.’ ”