From the Monitor archives: After the fall of the Berlin Wall, what's next?

Loading...

This article originally appeared in the Nov. 13, 1989, edition of The Christian Science Monitor.

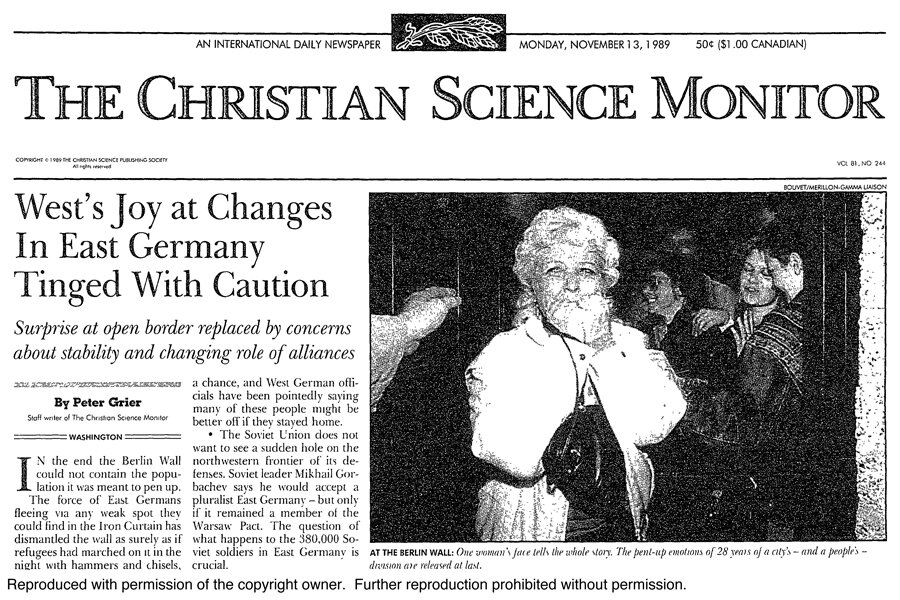

West’s Joy at Changes In East Germany Tinged With Caution

Surprise at open border replaced by concerns about stability and changing role of alliances

WASHINGTON – In the end the Berlin Wall could not contain the population it was meant to pen up.

The force of East Germans could find in the Iron Curtain has dismantled the wall as surely as if refugees had marched on it in the night with hammers and chisels, leaving it smaller each morning.

The opening of the East German frontier is a reminder that police states are not forever, and that even repressive governments must worry about maintaining legitimacy in the eyes of the governed. But the act is a symbol, not a solution. East German leaders must likely enact further political and economic reforms to stop the outward rush of citizens.

The speed with which East Germany has spun into turmoil has stunned the West, even after the examples of Poland and Hungary. A sense of caution, and worry about the long-term issue of German reunification, is keeping many officials and analysts in the US from being too euphoric.

“It is in nobody’s interest that East Germany collapse prematurely,” says Ronald Asmus, a RAND Corporation analyst.

• West Germany does not want to be faced with a larger refugee problem than it already has. Western experts figure about 1.4 million of East Germany’s 16 million people might flee if given a chance, and West German officials have been pointedly saying many of these people might be better off if they stayed home.

• The Soviet Union does not want to see a sudden hole on the northwestern frontier of its defenses. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev says he would accept a pluralist East Germany – but only if it remained a member of the Warsaw Pact. The question of what happens to the 380,000 Soviet soldiers in East Germany is crucial.

• The United States does not want the Soviet Union to get nervous and cool improving relations. In recent months the White House has reassured the Soviets that US policy in Eastern Europe is not designed to threaten their security. “There’s a very positive interplay” between the superpowers, a US official says.

News about the dramatic East German move raced through Washington last Thursday with a rapidity unmatched by the San Francisco earthquake.

When President Bush fielded questions on the subject, the issue quickly became not the move itself, but whether Bush was excited. “The fact that I’m not bubbling over ... maybe it’s getting along toward evening because I feel very good about it,” he said.

Throughout the dramatic Eastern European fall, there’s been frustration in Washington about being on the sidelines. US officials say over and over that there is only so much they can do to influence the situation.

The abolition of travel restrictions carried with a hint of desperation on the part of new East German leader Egon Krenz. He seemed to be offering East Germans a chance to think, and calmly assess their situation.

“It’s the only way they can maintain their hold on power,” says Hannah Decker, a University of Houston professor of German history. But dramatic as the gesture is, it can only be a short-term solution to Mr. Krenz’s problems. Unless coupled with further reforms it is unlikely to stem the emigrant tide, US analysts say.

Krenz has called in a general way for such reforms as freedom of assembly and the press, and eventual elections. A conference of the East German Communist Party is slated for mid-December.

Free elections could be the key to quieting dissent, but it is unclear whether Krenz is committed to them. The opportunity to choose leaders might give East Germans an incentive to stay and rebuild. “The next step has to be real political change, real pluralism,” says David Gress, a Hoover Institution scholar.

For Western nations, the East German government’s moves toward change represent a clear moral victory. But there is underlying concern that the situation could spiral out of control.

West Germany used to take up to two years to educate refugees from the East in the ways of a free society, but with 225,000 East Germans arriving this year such readjustment is no longer possible. Integration of those already there will be a strain.

To the US, stability in this context means a continued standoff between the military alliances of the Warsaw Pact and NATO. The East German situation could threaten this stability in two ways.

In the first, a newly pluralist East Germany could attempt to declare itself neutral. This could be unacceptable to the USSR. East Germany blocks the historic western approach to Russia, and is thus important militarily.

In the second, West Germany might declare itself neutral at the cost of long-sought reunification. A new mini-superpower would be created, one both West and East may view with unease.

The reunification question remains the central German problem. There are many ways of uniting short of one government – a loose confederation, perhaps, or a sort of economic union.

"Just because things are exciting we should not jump to conclusions,” says Helga Welsh, a University of South Carolina German policy expert. “This is going to be a long process.”