Now on the threshold of the French presidency, who is Marine Le Pen?

Loading...

| Paris

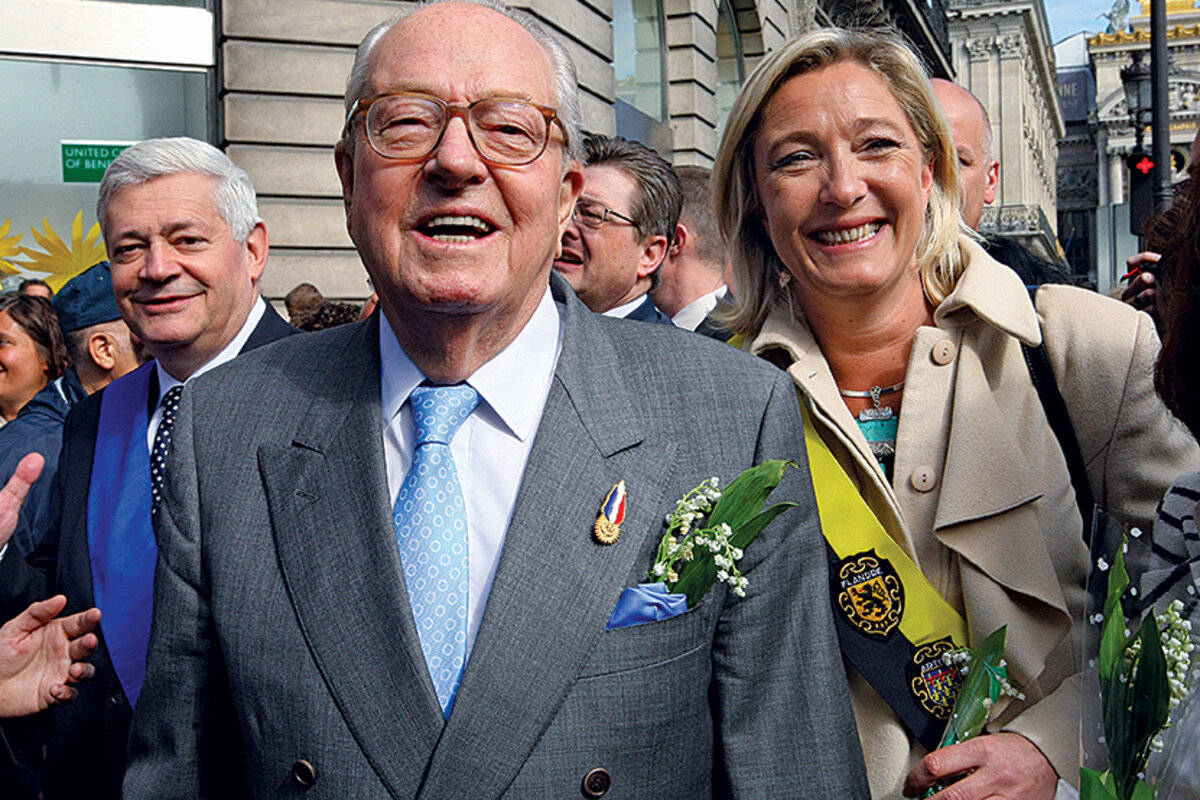

When Marine Le Pen was a child growing up in Paris, her friends never slept over – their parents wouldn’t allow it. And no matter how hard the blond, blue-eyed girl studied at school, her teachers often mocked her, hardly concealing their disdain. Her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, was so reviled in French mainstream society that someone set off a bomb in the stairwell outside their apartment four years after he founded the fringe far-right National Front (FN) political party in 1972.

Ms. Le Pen describes in her autobiography, “A Contre Flots,” or “Against the Current,” a childhood that was full of insults, suffering, and injustice – all simply because of her family name.

She cannot say the same of her adulthood.

The girl who grew up in the harsh shadow of her provocative, nationalist father has risen to become one of the most popular politicians in France – and one of the most important opposition leaders in the world. Now, as the campaign for the French presidency reaches its denouement – with Le Pen having a distant but not inconceivable chance of winning – she has pushed the FN closer to the Élysée Palace than her father ever did and is expanding her influence over French and European politics.

The party leader, who is both anti-immigrant and anti-European Union, inspires an almost cultlike following. She now garners support among large swaths of the population, including a growing number of mainstream voters who once rejected her. Many of them carry photos of her in their wallets.

At rallies, supporters chant her name in trancelike reverence. “Marine! Marine! Marine!” came the cry at a recent campaign stop in Metz in France’s Grand Est, a former mining region that’s reeling economically.

Le Pen, tall and confident, walked onto the stage cutting a striking figure. She was dressed modestly, as is her style, in a dark blue blouse cut out at the shoulders that was at once feminine and authoritative. The arena was filled with those who want out of the EU, who want immigrants out of France, who want the ruling elite out of office. And if they are separated by disparate, and sometimes irreconcilable desires – some eschew her left-wing protectionist trade policies but love her right-wing crusade to stop foreigners from coming in – they seem united in a longing for the grandeur of a France they can barely grasp anymore.

In voices thick with nostalgia, these voters – and the candidate they would elevate – may well decide the future of Europe. The EU, the postwar bloc that France helped to found, probably couldn’t survive if the country withdraws from the organization, which is what Le Pen wants to have happen.

The following that she has amassed both reflects and reinforces the nationalist revival sweeping across Europe and around much of the world. The populist rebellions in so many countries that shun globalism, open borders, and multiculturalism may be the most dominant political trend of the 21st century – and perhaps no one embodies the mood of the movements better than Le Pen.

She is not just Donald Trump with a more natural hairdo and a French accent. Her political roots date back to her teenage years, her rise has been methodical, and she is peaking in popularity at the most important moment for Europe in a half-century – one that may decide whether the EU survives or splits apart.

“This is the cleavage of 21st-century democracies,” says Pascal Perrineau, an expert on populist movements at Sciences Po in Paris. “It’s not a cleavage between the right and left anymore, or between conservatives and progressives. It’s a new kind of split between open societies and closed societies.”

In the second round of elections May 7. In a field of 11 candidates, she and Emmanuel Macron, a 39-year-old former investment banker who broke from the ruling Socialists to start his own upstart party, En Marche, were the top winners in round one Sunday.

That means it will come down to the pro-EU, pro-free trade Macron against the antiglobalization, anti-immigrant Le Pen – illustrating the dichotomies running through Western societies. Polls for now give a significant edge to Macron in the second round, and the two mainstream parties put their support behind Macron, but in an era when Mr. Trump and “Brexit” triumphed, no one is predicting an unequivocal defeat for Le Pen.

“Macron speaks to the France that is doing well,” says Mr. Perrineau. “Marine Le Pen speaks to the France that is not doing well.”

The region of undulating hills around Metz is sometimes called the “Country of Three Borders” because it is where France, Germany, and Luxembourg meet. If anyplace can call itself the heart of Europe, it is here. As FN supporters entered the arena for Le Pen’s rally on a rainy Saturday, the mayor of Metz, Dominique Gros, was hosting a mini ceremony just a few blocks away celebrating Franco-German friendship week.

Mr. Gros’s father fought in the French Resistance against the Germans. His grandfather died in the epic Battle of Verdun in World War I. His great-great-grandfather fought in the Franco-Prussian War. Gros himself was born in 1943, in the middle of World War II. “I learned when I was little that Germany was our enemy,” he says. “But we have succeeded in overcoming our ancestral hate ... and we must fight against this disastrous trend that risks pitting one against the other like in older times.”

Gros is, in other words, a strong advocate of an integrated Europe.

But if this region is a story of overcoming animosity through shared interests, it’s also one of globalization and deindustrialization. It is the disappearance of jobs, and the loss of dignity as a result, that have turned many Metz voters toward Le Pen.

At the candidate’s rally, Camille Ajac says she supports a “Europe of nations” but not the EU, which she calls “a Europe of interdependence.” “We absolutely want to get our sovereignty back,” she says.

Jean Schweitzer, a baby boomer, says he simply wants to give a new party a chance “since neither the right nor left has gotten us anywhere, and meanwhile France just gets worse.” Antoine Dupont talks angrily about his grandmother’s financial woes. At age 82, she’s been reduced to knitting stuffed animals to supplement her pension. He complains, too, that younger people are being forced to leave the country to find higher-paying jobs.

They all believe France’s future depends on the politician whom they describe as frank, simple, and honest – someone who could be a charismatic next-door neighbor.

Le Pen promises to hold a referendum on EU membership – what is called a “Frexit” vote – if she becomes president. At a rally in Lille, France, in March marking the 60th anniversary of the EU, she said flatly that “the European Union will die,” adding, “the time has come to defeat globalists.” She has called for the reintroduction of a new French currency, though she’s softened her tone in response to polls showing the vast majority of French want to keep the euro.

Advocates of European unity believe France’s departure from the EU would be catastrophic. “The EU can survive without the [United Kingdom]. It wasn’t there in the first place. It’s always been sort of half in and half out,” says Douglas Webber, professor of political science at INSEAD, a business school outside Paris. “But if France is no longer there, then basically you are missing not just a foot, you are missing an arm, and a leg, and a good part of the torso. This would be a political ... revolution of the highest magnitude on the Richter scale.”

Le Pen’s stance on national identity – preventing more foreigners from coming in and diluting what it means to be French – resonates as much as any issue with her followers. It’s also what makes her sound the most like her father. She wants to reimpose immigration controls at the border. She promises to prevent companies from relocating abroad for cheaper labor.

While detractors criticize her for stirring up hate, pointing often to a statement she made in 2010 comparing Muslims praying in the streets with the Nazi occupation of France, she has tapped into a deep anxiety about radical Islam in France. It has been fed by major terrorist attacks in Paris and Nice that together killed more than 230 people. At the same time, 1.3 million refugees and asylum-seekers, mostly Muslim, have entered Europe in the throes of upheaval in the Middle East, which the far-right easily conflates with terrorism.

“Let’s give France back to France,” says Le Pen at the Metz rally.

As her followers chant “On est chez nous,” or “We are in our house,” she adds: “What I want is not to close the borders. It is simply to have them – and control them.”

For all her hard-line stances on immigration and the EU, it would be incorrect to classify Le Pen as simply far-right. She has, for instance, adopted a protectionist trade agenda that is increasingly attracting some former socialist and even communist voters.

On two other litmus-test issues, gay marriage and abortion, she has toned down her message or remained largely silent. The social conservative branch of the FN seems to be appeased by the voice of Le Pen’s niece, rising star Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, who is a devout Roman Catholic and opposed to both. Yet the views of Le Pen herself, born in the pivotal year of 1968 amid student protests to what one family biographer calls a “bourgeois bohemian” mother, remain ambiguous. Her top adviser, Florian Philippot, is gay.

“Certainly in the ’70s the FN was from the extreme right, but today all the parties that shake European political life, that are creating the surprises ... they are more complex than just a single party from the extreme right,” says Perrineau.

In recent years, Le Pen has also tried to scrub the FN of its darker associations. She has kicked out members who publicly spew the kind of vitriol that was characteristic of her father and attempted to change the party’s image of being a party of racist old men.

The real inflection point came in 2015. Her father repeated a comment that over the years has refused to fade from memory. Jean-Marie stood by his assertion, first made in 1987, that the gas chambers of the Holocaust were a mere “detail” in history. Marine banished him from the party and publicly severed their relationship. Many observers have wondered whether the rupture was genuine, or just a brilliant moment of rebranding. Those close to her say it was painful and has been permanent and shows how politics always comes first with the Le Pens.

“You don’t break with your father in public on TV and have it not be difficult. It’s incomprehensible,” says Bertrand Dutheil de la Rochère, one of her advisers. “But her father was impossible, just going from provocation to provocation. The FN and Marine don’t need provocation.”

Her campaign posters now bear just her first name, not her last, with the words: “In the name of the people.” The logo, now a blue rose, used to be a flame.

The steeliness that has helped Le Pen rise to the pinnacle of French politics may be rooted in that cold night in November 1976 when a 44-pound bomb went off in the family’s Paris apartment building. The explosion damaged 12 dwellings and sent a baby flying out a fifth-floor window. Amazingly, no one was hurt in the incident – including the child, who landed in a tree along with his mattress. To this day, no one knows who planted the bomb. But Le Pen, who was 8 at the time, has written that she emerged from the incident “no longer a little girl like everyone else.”

The youngest of three sisters, Le Pen and her family moved to the wealthy, western suburb of Saint-Cloud to a mansion called Montretout. Today it is tucked within a gated community and carries an air of serenity.

But Olivier Beaumont, a French journalist who wrote the book “In the Hell of Montretout,” compares it to the house in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” a place that bore witness to unconventional tragedy, forming Le Pen’s tough character and ability to rise in politics as an unloved outsider. “Her whole story is one of rupture, departures, doors slamming,” he says.

The constant antipathy directed at her father hung over the family. Ultimately her mother, Pierrette, left – moving out one day when Le Pen was 16. The distraught teen waited for her mother at the entrance of her high school every day for several weeks, certain she would come home. Instead her mother moved to the United States with a lover, leaking explosive commentary about her ex-husband. At one point, she posed for Playboy magazine. The humiliation was too much for young Marine: She didn’t talk to her mother again for 15 years.

Le Pen’s entree into politics came at age 15, when her father let her miss school for a week and join him on the campaign trail. Jean-Lin Lacapelle, one of her old friends and an FN official today, says no one at the time saw in her a French president. She didn’t want the life of a politician.

Instead it was Marine’s older sister Marie-Caroline who was expected to take up that mantle, before she and her father had a falling-out and broke ties. Marine, in the meantime, became a lawyer and handled the party’s legal affairs.

In 2002, Jean-Marie made it to the second round of the presidential elections to face Jacques Chirac, stunning the nation. Marine went on air to talk about it. She was in her early 30s, all smiles and optimism.

“The day after, at the headquarters of the Front National in Saint-Cloud, all of the press arrived asking, ‘Where is Marine Le Pen? Where is Marine Le Pen?’ ” says Mr. Lacapelle. “It was incredible.”

He says that’s when he knew she would take the party to the top.

Though older and more polished now, Le Pen still has a blunt, charismatic style that appeals to French youth. The FN is one of the most popular parties in France among people ages 18 to 24, though the last minute surge of communist-backed Jean-Luc Mélenchon ate into its score Sunday night, bumping it down to the no. 2 party among the demographic.

Part of her allure is rooted in the plight of young people in the world’s sixth-largest economy, nearly a quarter of whom are unemployed. On the eve of Le Pen’s rally in Metz, 20-something supporters from across the country came together in the city’s party headquarters to discuss their plans for the following day. It had more the feel of an awkward school dance than a strategy session – they had put out bowls of potato chips and bottles of soda.

Emilien Noé, a former Socialist who coordinates the youth movement in the region, says young people are drawn to the FN’s promise to restore French glory, something they’ve never known. “A lot of young people are living abroad instead of in France, and this is sad for a country like ours,” he says.

While many Millennials are attracted to Le Pen because they see her as a rebel – one poster in the FN’s national headquarters trumpets “The rebel wave” – the candidate herself doesn’t act like the icon of a rebellion. In campaign imagery she is more likely to be photographed feeding cows and cuddling kittens.

When she reveals pieces of her personal life, it’s often in the context of a mother of three children in their late teens. Friends say the twice-divorced politician is a workaholic. But when she does relax, one of her outlets is karaoke. Her choices reveal her era: With her raspy voice, she likes to belt out the songs of Dalida, the Egyptian-born Italian diva who was a global phenomenon from the 1960s into the ’80s.

Le Pen has made inroads with other voters, too, including women. She doesn’t carry the feminist mantle. That she would be the first female president of her country is hardly a factor the way it was with Hillary Clinton.

But she has positioned herself as a defender of women against the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. She wants the Islamic veil banned, as well as the burkini, saying neither belong in modern French society.

“We believe that a woman in a veil seems not to be free,” says Marie-Hélène de Lacoste Lareymondie, a regional counselor for the FN in the Grand Est.

She says women recognize themselves in Le Pen, a divorced single mother. “She is a feminist, of course,” says Ms. Lacoste Lareymondie. “But she represents all kinds of women – mothers, lawyers, working women, political women. It’s complete.”

Not everyone buys it. Critics say her feminism is barely disguised discrimination against Muslims. At some public rallies, protesters denounce her as a “fake feminist.”

Le Pen’s mother had two nicknames for Marine growing up: “Miss bonne humeur,” or “Miss good mood,” because of her resolutely joyful and optimistic nature, she writes in “Against the Current.” The other was “Miss Trompe la morte,” or “Miss Daredevil,” because of a fearlessness she showed as a child, whether on a bicycle or skis.

It’s the intrepidness that seems to rally her base.

In the FN’s newest campaign video, Le Pen is facing the sea as an emotionally charged soundtrack pounds in the background. It feels like the trailer for a film. In a voice-over, she proclaims her love of France, the “age-old nation that does not submit.” She promises to stand up against the “sufferings of” and “insults to” the country. The video ends with her behind the wheel of a boat, a clear metaphor for one of her main campaign slogans, to steer the country toward what will “put France in order.”

The unsubtle subtext is that Paris needs the kind of strong leadership that has been missing under President François Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy before him. The French have always sought a “strongman” in their presidents, a monarchical instinct that turns them toward authority, especially in times of crisis.

“This is the country that produced Napoleon, the country that produced Charles de Gaulle,” says Perrineau.

But he sees protest as the stronger current pushing Le Pen toward the doors of the Élysée. He references French intellectual Pierre Rosanvallon, who said it’s no longer a time of elections in Western society. It is the time of “dis-elections.”

In the end, many French voters, says Perrineau, “just want to vote in the bogeyman.”

• An earlier version of this story ran before the first round of the French presidential elections.