Grenfell fire casts harsh light on London's dwindling low-income housing

Loading...

| London

It was just after 1 a.m. when Tomassina Hessel heard the knock on her door. Wake up, shouted a neighbor. “The tower is on fire!”

The tower was Grenfell, a 24-story residential block that Ms. Hessel’s low-rise building abutted, part of the same public-housing estate. She ran to the window and saw the flames rippling up the side of the tower; when she cracked it open she heard the screams.

When it came time to evacuate, she carried Jesse, her 3-year-old son, down four flights of stairs of her building, which wasn’t burning. Grenfell Tower was a torch in the dark night, a charnel house that would claim at least 80 lives in London’s deadliest fire since the Nazi bombing in World War II.

Nine weeks on, Hessel is living in a hotel room with her son, one of hundreds of evacuees from the estate. Some have moved back into the undamaged buildings, but most are waiting on offers of rehousing, unsure if they want to live in the shadow of the blackened tower. “We need to know what happened with the tower and about the fire safety in our building,” says Hessel.

The Grenfell fire exposed the shoddy standards and lax regulations governing Britain’s housing stock. Police have opened a criminal investigation into why a tower refurbished last year with public money and clad with cut-price aluminum went up in flames so rapidly and thoroughly.

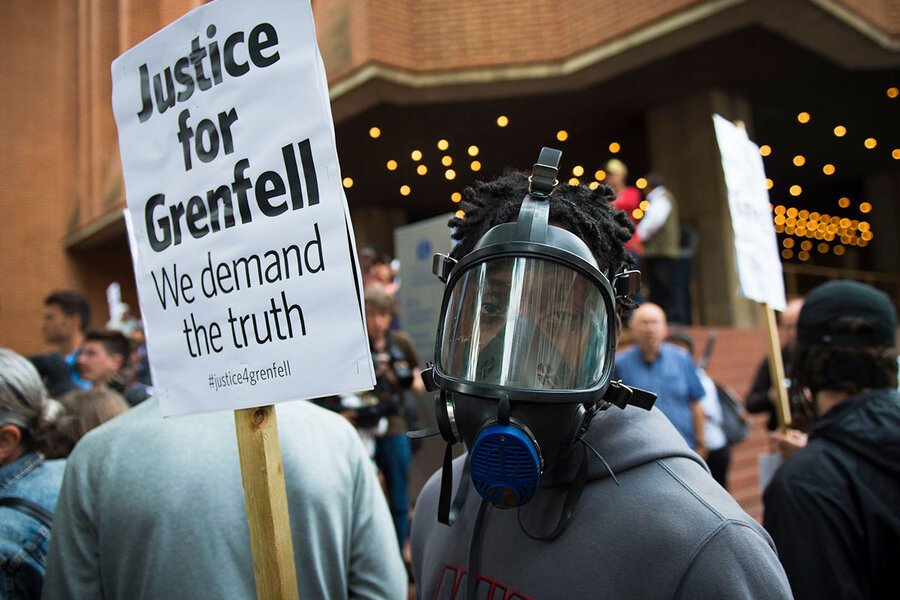

But the other exposé at Grenfell, one that packs a political punch, is the vanishing toeholds for the working poor in a city of global wealth, rapid gentrification, and a shrinking welfare state. As the cash-strapped councils that administer London's core functions, including public housing, have courted private developers to build more homes, public-housing residents have been squeezed out by what critics call the “social cleansing” of Britain’s capital.

That the number of public-housing units in London has not kept pace with demand is not news. But the tragedy at Grenfell has shone a spotlight on housing policy and raised questions over who benefits from London’s real-estate boom – and who falls through the cracks.

London’s housing crisis has been decades in the making, says Paul Watt, reader in urban studies at Birkbeck College in the University of London. The media’s attention has primarily been on the plight of middle-class renters who can’t afford to buy homes without family money, rather than the pressure on working-class Londoners who rely on public subsidies.

A judge leading an official inquiry into the fire said this week that its remit wouldn’t include a review of social housing policy, despite calls from local residents to do so. For many service workers on low wages though, “social housing” is virtually the only affordable option in much of London, where house prices have risen fivefold since 1995.

“The dominant narrative of the last decades has been that social housing is full of wasters and scroungers who can’t get on the housing ladder. I think what Grenfell has done is re-humanized social housing and made the issue of social-housing provision much more important,” Mr. Watt says.

Mixed community

Britain’s postwar reconstruction leaned heavily on public housing that was not just for the poor but as “the living tapestry of a mixed community,” in the words of their political architect. Victorian slums were cleared and replaced by modern apartment blocks. This wave of social housing continued into the 1970s when Grenfell Tower went up in North Kensington.

In 1981, 35 percent of Londoners rented from their council or a nonprofit association. Then came Margaret Thatcher, the Conservative prime minister who led the privatization of public assets, including the discounted sale of council-owned homes to their tenants. This policy initially boosted homeownership but was coupled with a freeze on new social housing. Over time, more households ended up in the private rental market. This land grab has intensified in recent years as the ruling Conservative Party has slashed housing subsidies and grants to local government in order to balance its budget. A 2016 parliamentary report found that 40 percent of former council homes belonged to landlords with multiple units.

Councils also began to unwind their direct role in social housing. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC), home to Britain’s wealthiest ZIP codes, handed off management of Grenfell and other estates to a nonprofit management agency. This agency has been heavily criticized for ignoring residents’ repeated complaints over fire safety.

On the streets around Grenfell, the posters on bus stops, brick walls, and storefronts tell their own story. Photos of missing residents posted in the first frantic days have faded; appeals for information have been replaced by handwritten RIPs and tributes. Many of the names are Muslim. Some were Asian and North African immigrants, say residents, along with other ethnic minorities living in the building, part of London’s multicultural stew.

“It takes years to build a community,” says Hessel, who was born in Germany and raised in London. “This community is so tight woven.”

Hessel moved into the estate in 2004 after becoming homeless as a student. She didn’t finish her degree but found work in catering and administration before taking time off when Jesse was born. The rent on her two-bedroom apartment is £550 ($700) a month, well below market rates in a neighborhood just a few miles from the prime properties of Notting Hill Gate and Kensington Palace.

Before the fire, Hessel had plans to start a digital marketing business, send her son to daycare, and find a private rental. She wanted to stay in the neighborhood, even if it meant paying £2,000 ($2,570) a month so they had access to public services and schools in a wealthy district. “I want to make sure that my son and I get the best out of life. We don’t want to remain poor.”

That proximity to wealth, and existing gentrification, has led to interest in Grenfell from developers. In 2009, consultants recommended that RBKC demolish the tower block in order to build a mix of luxury and affordable housing on the site. That plan was never pursued. Instead, the council decided on a renovation of Grenfell that added more units and lower-floor facilities.

Another addition: New aluminum siding and insulation. Last year the council’s then leader praised the renovation. “It is remarkable to see first-hand how the cladding has lifted the external appearance of the tower and how the improvements inside people’s homes will make a big difference to their day-to-day lives,” said Nicholas Paget-Brown, who resigned after the fire.

Driving out low-income tenants?

While Grenfell was spared the wrecking ball, councils across London have pursued ambitious regeneration projects that critics say inevitably push out low-income tenants and homeowners.

Conservative think tanks argue that decaying public housing located in expensive districts offer a partial solution to London’s chronic lack of housing. By selling sought-after land to private developers, councils can increase housing density, ease upward pressure on private rents, and free up resources for social housing elsewhere.

London’s elected assembly issued a report in 2015 on council regeneration projects over the past decade. It found that the number of homes had nearly doubled to 67,601, including affordable units for middle-class families, while “social housing” shrank by 8,000 units.

Even the apparent gains in mid-priced properties are mixed, says Mr. Watt. Affordable is defined as 80 percent of market rates, which rise with redevelopment and displace longtime residents. “The only genuinely affordable element is social rented housing, and that’s going down,” he says.

Stephen Timms, an opposition lawmaker in East London, often sees constituents about to lose their privately rented homes. But councils no longer have spare units, even to house families that face eviction, so they look for social housing in other cities. “Some that are becoming homeless are being told, here’s a place for you in Birmingham,” says Mr. Timms.

For families with jobs in London and kids in local schools, that’s a terrible bind. “It’s causing huge hardship and I think over time it will undermine the viability of London,” he says.

Asked in 2010 about government cuts in housing subsidies, then-Mayor Boris Johnson said he opposed the “social cleansing” of low-income renters. "The last thing we want to have in our city is a situation such as Paris where the less well-off are pushed out to the suburbs,” he said.

But that is what critics say is happening and why communities like Grenfell feel so embattled in the face of council redevelopment plans that make them feel like unwanted guests.

“Many want the poor to leave London. They believe that if you’re in social housing you must be on welfare. This is nonsense,” says Chris Imafidon, an educator and local resident.

Seeing the big picture

A week after the fire, Hessel went back to her apartment. “I walked in and I walked out. I left everything,” she says. Since then, she’s gone back to retrieve documents and collect toys for Jesse. But she’s not ready to move back and is weighing her options for temporary rehousing.

After the fire, Jesse seemed fine. But one night his father – the couple aren’t together – was reading him a book when Jesse told him that his house had burned down. It was the first time he had spoken of the incident. “He imagined that it had happened to him,” says Hessel.

Lately Hessel has begun rethinking her career plans. Helping brands to market online no longer seems such a worthwhile goal, she says. Her involvement with Grenfell survivors and activist groups, and exposure to the workings of government and emergency services, got her thinking about community engagement and why Grenfell residents were ignored for so long. Perhaps this is what she should be doing with her life, she muses.

“I was aware of all of the issues. I was angry about all these issues. But I was isolated. I didn’t know how to go about doing anything,” she says. Now she sees the big picture – and what’s missing. “The government needs to start investing in social housing.”