Briefing: Is Macron set to finally smooth Franco-African relations?

| Paris

As French President Emmanuel Macron approaches the end of his first year in office, he, like many presidents before him, has the ominous job of navigating France’s complicated relationship with Africa. “Françafrique” – the special and often murky business and political relationship that France shares with its former African colonies – is a political sticking point that has plagued former French leaders for decades.

Mr. Macron heads to Senegal Thursday on his fourth presidential visit to sub-Saharan Africa. Co-hosting the Global Partnership for Education Financing Conference with Senegalese President Macky Sall, he’ll be looking to show France’s commitment to an equal relationship with its African neighbors.

Can Macron modernize Françafrique once and for all, and what is at stake if he succeeds?

What is Françafrique?

The term “Françafrique” was first coined in 1955 by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Côte d’Ivoire, as a way to tout the country’s positive economic and political gains thanks to its alliance with France. But in recent years the term has turned sour, coming to describe the unequal and neocolonial relationship France upholds with its former African colonies and a pattern of French-supported dictators offering French companies lucrative contracts.

France continues to exert control over French-speaking Africa through diverse means. The West African CFA franc – guaranteed by the French treasury and pegged to the euro – is still the official currency in 12 former French colonies, despite their independence from France nearly 60 years ago. And French remains the official language in around 20 African countries.

France also maintains powerful ties with Africa through its business operations in sectors such as telecommunications, gas and electricity, and infrastructure. And since the 1980s, France has been involved in a series of military interventions in Africa, most recently in Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Central African Republic during former Presidents Nicolas Sarkozy’s and François Hollande’s terms.

Why is Françafrique considered a problem?

While Africa has benefited economically from its special relationship with France, especially in terms of its business and trade operations, France has undeniably benefited more and the alliance has hindered the continent from becoming fully independent.

“The relationship between France and its former African colonies is complex and has caused major hang-ups,” says Philippe Hugon, an Africa researcher at the Paris-based think tank IRIS. “Despite the decolonization and globalization of Africa, there are few domains where France is not involved.”

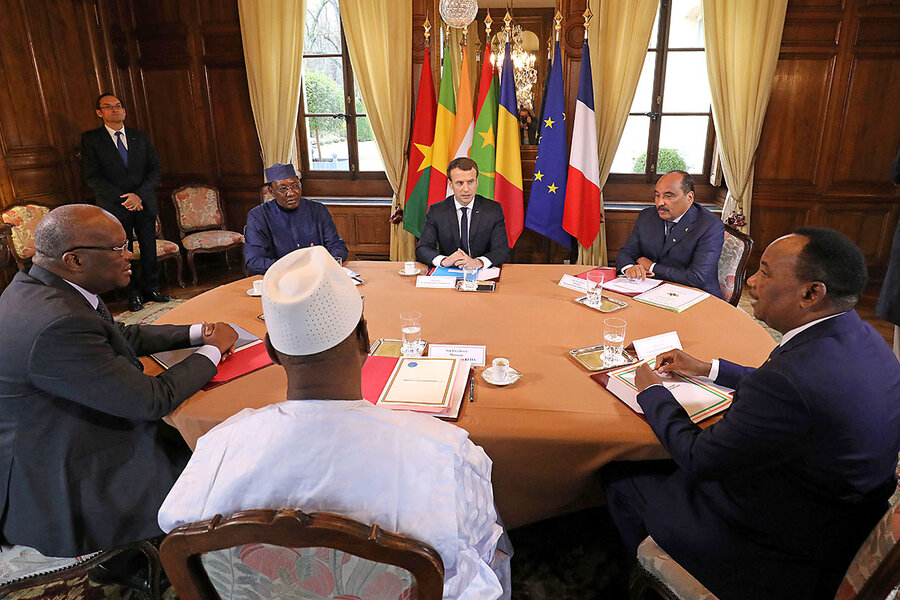

The political coziness between French and African leaders has also been heavily criticized over the years. France has been seen as complicit in allowing African dictators like Chadian President Idriss Déby and Togo’s former President Gnassingbé Eyadéma to remain in power, by providing support both privately and publicly. Ex-French President Jacques Chirac once described Eyadéma as “a close personal friend of mine and of France.” In return, it has been widely alleged, a number of African dictators funded Mr. Chirac’s presidential campaigns.

France’s dominance over the French language is also seen by some as a type of “cultural imperialism” that helps maintain France’s influence in Africa and ultimately doesn’t allow Africa to advance on its own two feet.

Why is it so hard to put an end to Françafrique?

France extricating itself from Africa would mean a prolonged, Brexit-style dismantling of treaties in the military, financial, economic, security, and trade sectors. Macron couldn’t realistically disassemble all that France has in place without great immediate peril for its economy – and Africa’s.

In addition, France benefits greatly from the relationship at a time when it desperately needs to boost its image around the world.

“France wants to pretend that it is still a world superpower but that simply is no longer the case,” says Patrick Farbiaz, director of Sortir du Colonialisme, a nongovernmental organization that fights against colonization. “The reality is that economically and politically, France is falling behind China, India, and the United States.

“In order to show its strength, it needs to maintain its influence in Africa and show that it has their support.”

The France-Africa relationship has also served to puff up the status of individual French presidents – aided in part by the fact that France’s African relations were long run directly out of the presidential palace, not out of the Foreign Ministry.

“Africa always gives a place for French presidents to be a big man,” says Douglas Yates, a professor of political science at the American Graduate School in Paris and an expert on African politics. “They arrive in a country, everyone is clapping, and they’re made to feel important. They don’t get that anywhere else.”

French presidents may begin their mandate pledging to end Françafrique, but as soon as they experience their warm African welcome, they often get more involved. Both Mr. Sarkozy and Mr. Hollande promised to end Françafrique, for example, but well into his mandate, Sarkozy enjoyed close relationships with several African dictators, while Hollande sent French troops into Mali within one year of his election.

Why is there hope that Macron might be able to address Françafrique?

Young, a political outsider, and with no business or political history with Africa, Macron could be the president to finally shift the power balance between France and Africa. From the start of his presidency, he has taken a different tone from his predecessors.

His willingness to acknowledge France’s responsibility for torture and massacres during Algeria’s eight-year civil war, as well as his insistence on creating a sense of equality between himself and his fellow African leaders, sometimes to his detriment, could point to a new way forward. Even changing the rhetoric surrounding the delicate subject would be more than any past president has succeeded in doing.

“This is the era of celebrity and image, and in a PR capacity, Macron has the ability to make a change,” says Mr. Yates. “If Macron can change France’s image in Africa but maintain the existing policies, that would be a success.”

But ultimately, Macron will have to take concrete steps to quiet his skeptics, who say his current treatment of Françafrique amounts to mere lip service. His partnership with Senegal in the Global Partnership for Education initiative, where leaders will work to convince developing countries to earmark 20 percent of their budgets towards education, is a positive step, as is a promise he made in November, during a trip to Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana, when he pledged to offer more scholarships for Africans to study in France.

“Education is a good investment and getting more Africans to come to French universities would have positive consequences for Africa,” says Yates. “It’s the best way to create ambassadors for French business and transmitters of French culture.”

How has Macron handled Françafrique so far?

It’s been primarily a diplomatic challenge so far, with some bumps.

A recent trip to Burkina Faso showed the fine line French presidents must tread when dealing with the issue of Françafrique. During a question and answer session at Ouagadougou University in November, a student asked Macron what he would do about the country’s constant power cuts. The French president replied, “You speak to me like I’m a colonial power, but I don’t want to look after electricity in Burkina Faso. That’s the job of your president.”

When Burkina Faso’s President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré later left the room, Macron joked, “You see, he’s gone. He’s left to fix the air-conditioning.” Macron’s comments set off a social media frenzy, with some criticizing him for paternalistic overtones, and others arguing that it was merely lighthearted humor. For his part, Macron said that his ability to joke with the African president showed their inherent equality.

What doors would open if Françafrique were resolved?

In the short term, France would likely suffer. With so many business, trade, and cultural influences in Africa, France’s economic and international influence would take a hit if it pulled its operations out of Africa. Africa, too, would find the cutting-off of existing ties with France hard economically.

But like the end of Spain’s colonial ties with Latin America, a breaking free from France would ultimately be a good thing for Africa, allowing it to truly become independent and rely on its own goods and services for economic, political, military, and cultural gain. Ideally, the two could become true partners without a sense of one dominating the other.