Are Greek and EU officials illegally deporting migrants to Turkey?

Loading...

| Athens and Orestiada, Greece

Under international law, refugees cannot be returned to a country where their life or freedom is at risk; once they have crossed a border, they must be allowed to apply for asylum if that is what they are seeking. But in Greece, it seems that legal standard is not being met. In multiple incidents reported by human rights groups and supported by a separate investigation by The Christian Science Monitor, migrants say they have been beaten and forcibly “pushed back” across the Evros River, which runs along the Greek-Turkish border. And they say that the perpetrators of the pushbacks have been Greek police officers and members of Frontex, the EU’s border agency. Police and Frontex officials deny involvement. But the violence against the migrants is well documented, and access to the border – a military zone – is highly restricted on the Greek side. “There is a significant body of evidence,” says Eleni Takou, deputy director of HumanRights360, one of the groups documenting the incidents. “Thirty-nine testimonies from us, 24 from Human Rights Watch.… It is becoming obvious that there are several groups in the region who do this.”

Why We Wrote This

While reporting in Greece on another story, Monitor correspondent Dominique Soguel heard tales of migrants being beaten and illegally expelled from the EU by border officials. So she investigated.

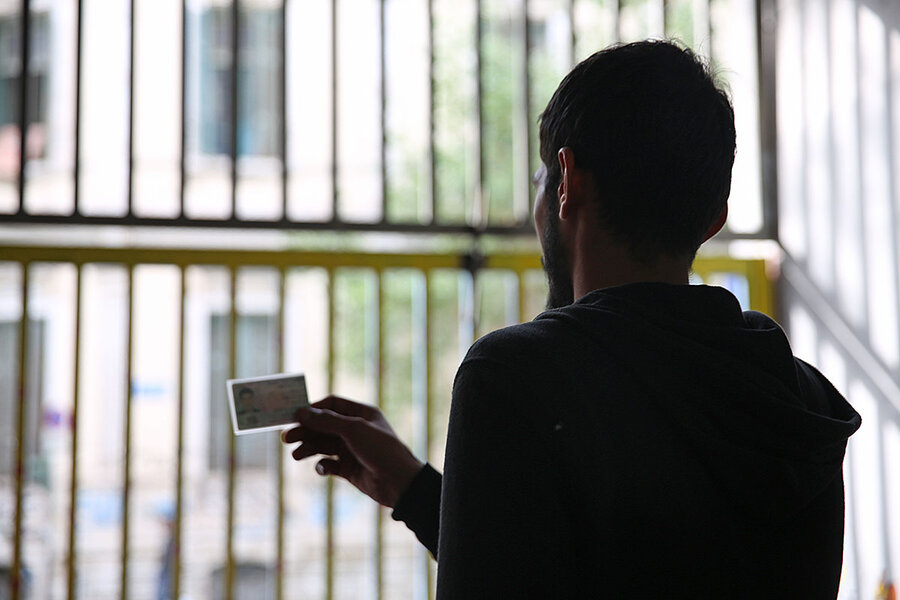

Fadi Jassem is a skinny Syrian man with sorrow etched on his face. He is one of more than a hundred refugee squatters living in a forsaken building in central Athens. The only document he holds is a Syrian identity card, chipped on the top corner. He blames Greek border police and Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, for his plight.

That’s because Mr. Jassem used to be living a relatively happy life in Germany as a recognized refugee with a three-year residency permit. But then he heard his little brother had gone missing hours after crossing from Turkey to Greece with the help of smugglers. The 11-year-old boy had just been ferried across the choppy waters of the Evros River in the middle of winter when he disappeared. “He got lost in the border area, so I went to search for him there,” Jassem told The Christian Science Monitor in October.

That's when it all went wrong for Jassem. “Greek police grabbed me and handed me over to Frontex. They destroyed all my documents. They put eight of us on a boat and pushed us back to Turkey.”

Why We Wrote This

While reporting in Greece on another story, Monitor correspondent Dominique Soguel heard tales of migrants being beaten and illegally expelled from the EU by border officials. So she investigated.

He assumes that the officials responsible were Frontex because they were masked and spoke German rather than Greek. The police officers, he says, beat and insulted him. It took Jassem many months and several attempts to manage to cross back into Greece from Turkey. Now he hopes that Germany will take him back.

Jassem became the victim of forced pushbacks, an illegal tactic of forcibly removing migrants from European soil, usually soon after they’ve crossed over the European Union’s external borders. The phenomenon is difficult to measure, in large part because of the outright denial by authorities that it is taking place. But evidence of its recurrence is growing, and human rights groups are sounding the alarm, concerned by the frequency and patterns of abuse relayed by migrants trying to reach Europe.

Illegal deportations?

Forced pushbacks are in violation of international law. A key principle of the 1951 Refugee Convention in Geneva, which has been signed by 148 states including Greece, is non-refoulement. The charter prohibits refugees being returned to a country where their life or freedom is at risk. Borders may be crossed irregularly and without documents when the intent is to request asylum; people fleeing war rarely have their documents in order, if at all.

The practice, according to humanitarian workers and human rights researchers with long track records in the Evros region, has long been a problem along the Turkey-Greek border. But the growing frequency of these incidents and the range of actors apparently involved has triggered alarm and a new push for accountability.

Human Rights Watch documented 24 incidents of pushbacks across the Evros River from Greece to Turkey this year. That tally is the outcome of interviews conducted with migrants on both sides of the border this year. Researcher Todor Gardos says they took a conservative approach to the figures. Even if an individual described being pushed back seven times, along with more than 100 other people, this was logged as one experience.

“If you turn up at a border police station in Greece now, it is a matter of lottery whether you get into the asylum or registration process, or whether you get pushed back,” says Mr. Gardos.

Several migrant men claimed Greek police and army officers brutally beat them with batons during the pushback. They expose their backs in a video, recirculated by HRW, as proof of their bruising. Greek social and legal service providers are also collecting evidence in the hope of triggering a change of attitudes from government officials and paving the way for accountability.

The Greek Council for Refugees, HumanRights360, and ARSIS (the Association for the Social Support of Youth) published 39 testimonies of people who attempted to enter Greece from the Evros border with Turkey but were forcibly pushed back. The Monitor has also spoken to refugees and smugglers in Turkey and Greece who tell similar stories. Details – like the destruction of personal documents and phones – repeat themselves.

The number of refugees and migrants arriving in Greece has dramatically dropped since 2015, when the EU and Turkey signed an agreement to send back to Turkey migrants who do not apply for asylum or whose claim was rejected. More migrants reach Greece from Turkey via the Aegean Sea compared to the land borders, although on average these witnessed more than 1,600 arrivals per month in 2018.

Migrant crossings and forced returns typically take place at night by most accounts, although police officials deny they are happening. A Syrian woman told the Monitor her children were stripped of their coats and shoes before being shuttled across the river to Turkey by masked men in the middle of the night.

“People pass the river and wait for the night to get into the mainland undetected,” says Eleni Takou, deputy director of HumanRights360. “If they are detected, Greek forces, military or police, take them to a detention place, which is not always a designated detention place; it could be a warehouse. Then there are people who take them back. They have a full face mask. Even if faces are visible, there is no insignia to identify them.”

Three residents of the riverside farming villages near Orestiada say that pushbacks are routine. They see them because their land flanks the military zone. The trio gave their accounts on condition of anonymity, as most residents have relatives serving in the Greek military and police.

One young farmer pointed out a river intersection where he said police carry out regular patrols and pushbacks. He says he has witnessed Greek police officers intercept migrants on arrival and load them into blue buses (typically used for arrests).

“These buses then drive into the fields, towards another point in the river,” he says. “There is no other reason to take them there. There is only the river, and they have the police boat with them. Why else would they take them there if not for pushbacks?”

A dangerous crossing

A senior Greek police officer rejected the notion that voluntary or involuntary returns were taking place at the river. He said asylum seekers are treated in line with international obligations, while those who do not seek international protection may be detained and then formally deported.

“The Greek police is in charge of protecting the borders and managing the migration flows,” said Paschalis Syritoudis, police director of Orestiada. “It is all inflow. There is no outflow.” Since the launch of Greece’s Operation Shield in 2012, he notes, 500 smugglers have been arrested and tried, more than 500 river boats confiscated.

Crossing the river by boat typically takes only five to 10 minutes, but bad weather can drag out the process and even turn the journey fatal. There have also been killings associated with the crossing. Three migrant women were found dead with their throats cut near the Evros River, also known as Maritsa.

“Both length and depth of the river vary a lot, especially in winter,” pointed out another officer in an informal conversation with the Monitor during an official visit to the giant wired wall reinforcing the land border. “During the summertime there are a few points that are so low you can just walk across. The vast majority cross the river at night, so the police have thermal cameras. That way they can see everything.”

He says Frontex officers and police conduct the patrols, although the army is also present. The nationalities change and rotations typically last three months. The Germans, however, appear to have a consistent presence, based on the accounts of local police, residents, and migrants.

Three migrants who described pushback experiences to the Monitor said “German commandos” ferried people back across the river to Turkey. Some, like Jassem, felt confident identifying the language; others were less certain. Testimonies in the HumanRights360 report include mention of German and other languages.

“There is a significant body of evidence,” says Ms. Takou, who believes Frontex, in addition to the Greek police and army, may have a role in systematic pushbacks. “Thirty-nine testimonies from us, 24 from Human Rights Watch.… It is becoming obvious that there are several groups in the region who do this.”

Is Frontex involved?

The involvement of Frontex, an EU-level organization, in the pushbacks would take the seriousness of the phenomenon up a level. Evidence of their participation in pushbacks is much thinner, though the behavior of which they are being accused is of far greater concern to those affected. “The biggest fear here is [of] Frontex,” says an aid worker who has access to detention and identification centers in the area. “They are the ones famous for beating and thefts.”

Smugglers and migrants allege that Frontex is involved in the pushback operations due to the differences in the uniforms worn and languages spoken by the masked officials from other Greek officers in what is officially a Greek military area. Legal and social service providers assisting asylum seekers in the border towns near Orestiada have come to similar conclusions. Movements in the region are closely monitored. The smaller dirt tracks that shadow the river as well as its banks are considered off-limits, complicating the efforts of local journalists and activists who have sought to document this issue and build up evidence. The same rules apply to foreign journalists.

In October, a Frontex spokesperson noted the agency’s officers were not directly involved in border patrols. “Our role is to provide additional technical assistance to those countries of the European Union that face increased migratory pressure,” said Izabella Cooper, who put the number of Frontex officers deployed in the Evros region at roughly 30. Officers who witness a code of conduct violation must file a report to headquarters in Warsaw.

Recontacted in December, Ms. Cooper said Frontex officers wore their country uniforms as well as an obvious blue armband as an identifier. “No officers deployed in Frontex’s operations have directly witnessed any of the alleged pushbacks, and no complaints have been made against any Frontex-deployed officers,” she said. “Despite the fact that the agency was not in any way involved, Frontex takes such information extremely seriously.”

Only one Frontex officer has flagged an “alleged pushback,” she said.

Christiana Kavvadia, a lawyer with the Greek Council for Refugees, wants responsible parties brought to trial. The key is ensuring that migrants who testify are adequately protected. “Everybody tells the same story on how it takes place,” she says in a late night interview in Alexandroupolis.

“They don’t distinguish between men, women, families, pregnant women,” she adds. “The problem is getting proof because they destroy phones and documents.”