Croatia needs tourists, but are tourists ready to return to Croatia?

Loading...

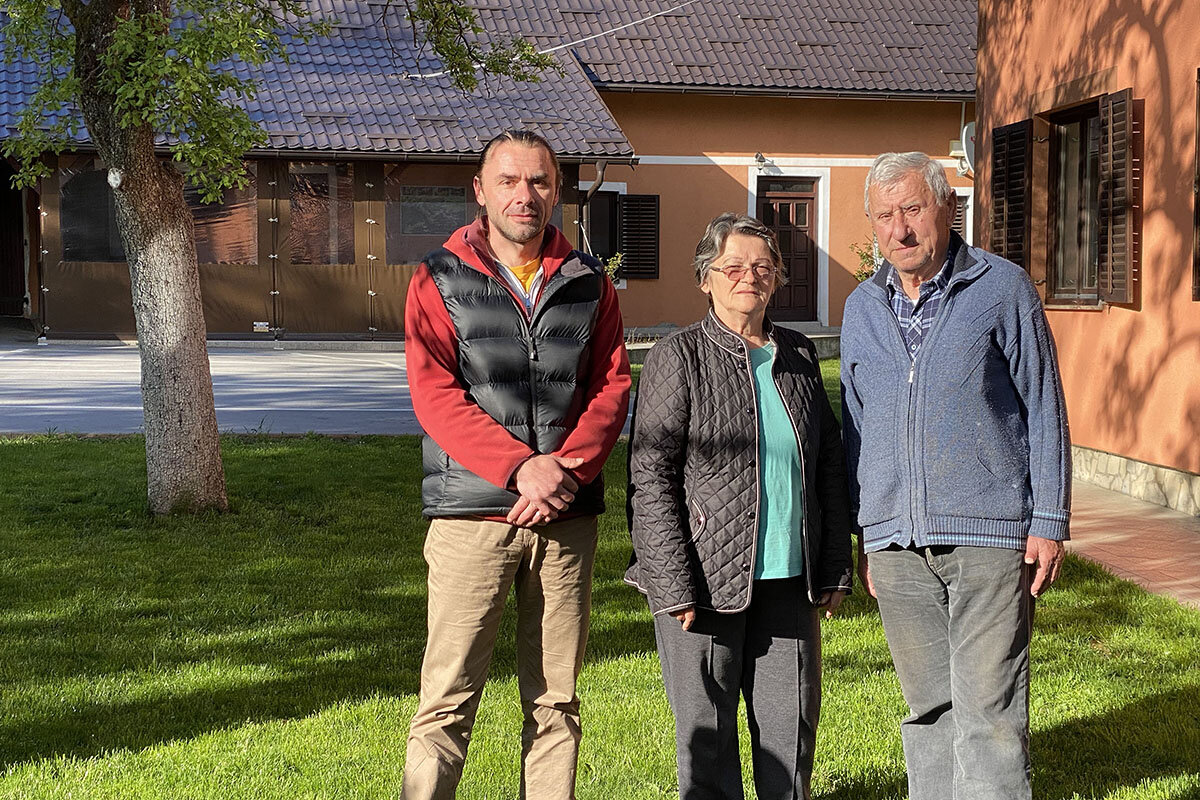

| Jezerce, Croatia

The pandemic made 2020 a brutal year for most countries economically. But it was particularly tough for Croatia, where tourism accounts for 20% of the gross domestic product of a country that rebuilt itself after a devastating civil war.

Croatia saw its best tourism year yet in 2019, capping a decadelong boom in which it joined the European Union, only to see revenues plummet during the pandemic. Now, the West is beginning to get back to some sense of normalcy, and the summer tourist season can’t come a moment too soon for Croatia.

Why We Wrote This

As people begin to feel safe enough to travel abroad again, Croatia could be a major beneficiary of the change in mood. And it won’t be a moment too soon for its tourism-dependent economy.

At his Italian restaurant in Split, Roberto Popowicz is also ready for tourists. Opening hours were cut 80% to 90% during the pandemic and he was forced to let go some staffers, even after borrowing money to keep Trattoria Tinel open.

“It was very, very stressful,” says Mr. Popowicz, surveying the indoor and shaded outdoor patio tables that typically serve up grilled squid and fish. But he’s hopeful for 2021.

“Croatia is first of all a tourist country, and many other industries are connected directly and indirectly with Croatian tourism,” says Kristjan Staničić of the Croatian National Tourist Board. “I think we can do even better in the future. I think that the comeback kid could be in 2023.”

Dusko Glumac’s personal history tracks Croatia’s route on the global tourism scene.

A teenager when the Yugoslav civil war broke out in 1991, Mr. Glumac was sent from this northern Croatian village to Belgrade, in Serbia, to finish school. His father – who’d worked as a server at ex-Yugoslavian leader Tito’s nearby lakeside villa – and his mother stayed behind to tend to the family’s bed-and-breakfast.

Soon enough, his parents left too, and regiments of the Croatian army took shelter in their property at the height of the war. Years later, the Glumac family trickled back home to find a land mine in their dining room and their belongings looted.

Why We Wrote This

As people begin to feel safe enough to travel abroad again, Croatia could be a major beneficiary of the change in mood. And it won’t be a moment too soon for its tourism-dependent economy.

“We had to rebuild everything bigger and better,” says Mr. Glumac of the boutique hotel business his grandfather started in the 1960s at this crossroads to Eastern Europe. Rebuild, the Glumac family did, restoring walls and windows, and over time upgrading the three-story main house with the addition of playgrounds and a gazebo. Over the past two decades, travelers from all over the world have visited their small property situated in the UNESCO-designated Plitvice Lakes region. KAL launched direct flights from Seoul, South Korea, to the nearby capital, Zagreb. Mr. Glumac met and married a Taiwanese woman.

Then the pandemic struck, challenging not only the family business but also Croatia’s newfound identity in the tourism world. The European country most dependent on tourism, Croatia had seen its best year ever in 2019, capping a decadelong boom in which it joined the European Union. Last year, tourism revenues plummeted by 90%.

Now, as the U.S. and Europe return to some sense of normalcy, the new tourist season can’t come a moment too soon for Croatia. With United and Delta opening direct routes in July from New York and Newark, New Jersey, to Croatia, and Europeans also on the move again, summer could bring back the tourists that the country is counting on to fuel a much-needed rebound.

“Croatia is first of all a tourist country, and many other industries are connected directly and indirectly with Croatian tourism,” says Kristjan Staničić, director of the Croatian National Tourist Board. “Most important in the moment right now is to focus, to improve the [pandemic] situation in Croatia” so more people will come, he adds. “I think we can do even better in the future. I think that the comeback kid could be in 2023.”

Croatia’s geographical advantages leap out from a glance at a map.

The country occupies almost the entire length of Adriatic Sea coastline opposite Italy. Between the medieval walled city of Dubrovnik in the south and capital city of Zagreb in the north stretch world-class scenery, rambling mountain ranges, lake regions replete with hiking, vineyards and olive groves, local cuisine, and historical depth to rival the rest of Europe.

“For a country that was part of a devastating Balkans war, to turn itself around to become a real hot spot for international travelers is quite a feat,” says Lloyd Figgins, a Britain-based travel risk consultant. “Croatia benefited from a real willingness to shake off the shackles of being associated with a terrible European war, a willingness of the people to really tell the world what they’ve got.”

And the world came. Made famous as the setting for “Westeros” in the smash-hit HBO series “Game of Thrones,” Dubrovnik began docking hundreds of cruise ships a year, and unleashing tens of thousands of passengers a day into the tiny town of 40,000. Countrywide, Croatia logged more than 400 million overnight stays in 2019; a handful of restaurants earned Michelin stars.

Then, 2020 brought only a tenth of the previous year’s business, a brutal blow to a country where tourism makes up nearly 20% of gross domestic product. While hotel chains and tour operators waited, some took the time to regroup.

“Before the crisis we were complaining about mass tourism,” says Ružica Herceg, managing partner of Zagreb-based Hotel & Destination Consulting. “And, maybe we should lift it to more higher quality supply. We need more investment and infrastructure and higher-quality projects.”

Some operators took the time to develop areas that lagged behind Croatia’s competitors, such as “experiential” packages that focus on aspects of local culture, or involve activities like kayaking and cycling. Sustainability is also a growing focus for a country hoping to minimize environmental impacts of having so many tourists, and the government is especially keen to draw tourists to inland lakes and mountain areas, away from the highly trafficked beach destinations.

If tourists can drag themselves away from the beach, they “can capitalize on a great opportunity to see a beautiful country, perhaps without the crowds,” says Mr. Figgins.

The waiting game

A ferry ride away from the beach town of Split, Marko Franulic sits on the island of Brac. He is waiting for tourists.

In 2019, almost 3,000 guests graced his stone patio, tasting his family’s olive oil and wines. He used to sell 90% of the family’s annual production, bottle by bottle, to visitors. This year, he had hosted only two groups of tourists by mid-May.

Mr. Franulic has vats of olives and crates of wine with nowhere to go. But he’s optimistic. This year he sees lots of grapes on the vine, and he hopes pandemic restrictions will be lifted in time to invite friends from the mainland to help with the annual harvest.

“If we have more friends we finish by 4 p.m. If not so many friends we finish at 7 p.m.,” says Mr. Franulic. “Then we eat.”

Back on the mainland, at his Italian restaurant in Split, Roberto Popowicz is also ready for tourists. He slashed opening hours by 80% to 90% during the pandemic and was forced to let some staffers go, even after borrowing money to keep Trattoria Tinel open. “It was very, very stressful,” says Mr. Popowicz, surveying the shaded outdoor patio tables where he typically serves up grilled squid and fish. But he’s hopeful for 2021.

And in Jezerce, Mr. Glumac waits too. As a boy, before the civil war, his world was confined to a small village school. Today his life is full of cultures brought together from all over the world. He and his Taiwanese wife are expecting their first child together. Tourists are starting to book again.

Mr. Glumac has put his property expansions plans on hold, but hopes to eventually build a home for his young family. In the meantime, while he can, he’s enjoying the natural beauty of the surrounding lakes, without the tourists.

“For an enjoyable time, I spend time in silence,” says Mr. Glumac. “I hear the birds; I walk along streams and look for river shrimp; I search for mushrooms. I just listen to the silence.”