In Pictures: Bucking Azorean traditions, these women take to sea

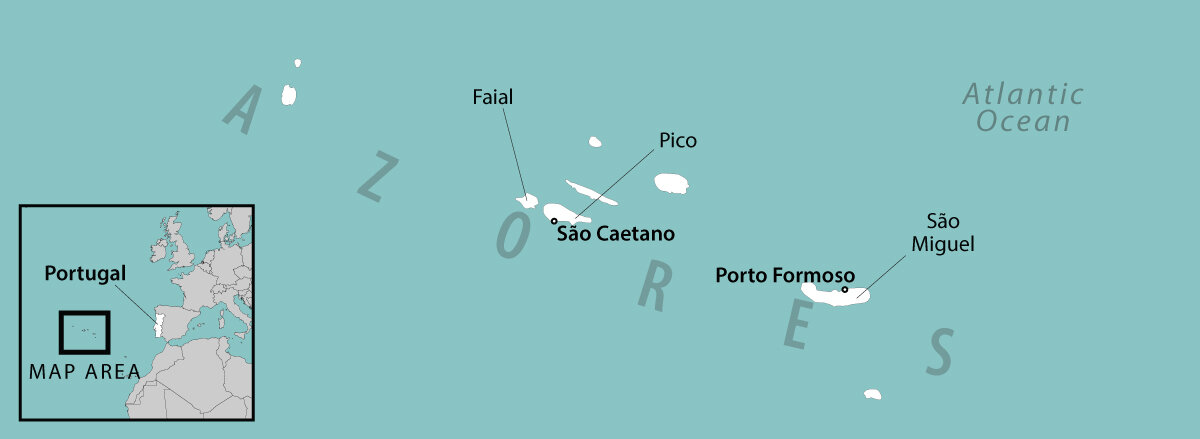

| Azores, Portugal

The traditional role of women in the Azores fishing industry was usually limited to the support they provided on land, whether in the preparation of troughs, bait, and nets or in the logistical work of cleaning and selling fish. But a small number of women, mostly in fishing families, have managed to go to sea, and they’ve found that the grueling work suits them.

In 2008, of the 153 women who worked in extractive fishing, only 12 worked at sea, according to Umar-Açores, a women’s rights group. Today there are only four, possibly the last Azorean fisherwomen. Women have historically been excluded from going out on boats because they were considered not strong enough to do the work, and because they were thought to be a distraction to male crews.

But as small fishing operations have struggled with higher costs, dwindling fish stocks, and steeper competition from larger boats, some fishing families have seen wives or daughters step up out of economic necessity.

Some of these women, like Lídia Silva, have found they liked the freedom of being out on the water, and they feel a sense of accomplishment in showing what women are capable of. Ms. Silva and her sister, Sara, helped their father on the family’s boat when their mother stopped going to sea. The low pay drove Sara to seek employment elsewhere, but Lídia has obtained a fishing license and says she hopes to take over from her father when he retires.

Even with all the difficulties inherent to the profession, Ms. Silva can’t see herself anywhere but on the sea.