Stay or leave? Ukrainians struggle as sounds of war draw close.

Loading...

| Bakhmut, Ukraine

Gennadi Borishpol doesn’t scare easily. But he knows that his hometown of Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine is among the next targets of Russia’s march into the Donbas.

The sound of war is constant, with artillery and rocket duels on the horizon to the north. Blasts of outgoing Ukrainian rounds erupt from inside the city; incoming fire is growing, including a strike overnight Tuesday that officials say left one civilian dead.

“You can hear it – the front line is coming,” said Mr. Borishpol, a former firefighter who was among first responders at the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onEven amid war, the desire to defend and protect one’s home is powerful. As Russian troops close in on the eastern town Bakhmut, many residents are reluctant to leave the only life they’ve ever known.

But that was two weeks ago. Now, Russia’s war has come much closer.

“It has been much louder these days,” says Mr. Borishpol, contacted by phone Wednesday. “Every other day there is incoming shelling. One was last night. But still, at least it is not every day.”

For now he is staying put, loath to flee the birthplace of his father and grandfather. Then there is his responsibility to others: He is in charge of a hostel where those displaced by the war, including older people brought by neighbors from nearby villages, can find temporary sanctuary, food, and a bed.

Like many of his neighbors, he grapples with resignation, patience, and the need for courage that is more evident every day. Some in the town deny that the war is coming – or coming for them. But for those who recognize the potential for an all-out assault as well as Russian occupation, difficult decisions about staying or leaving their lives behind for an uncertain future loom large. They’re rendered all the more complex by ubiquitous Russian television news, which portrays Ukraine as the aggressor nation, even bombing its own cities in some conspiratorial play for global sympathy.

Just miles away

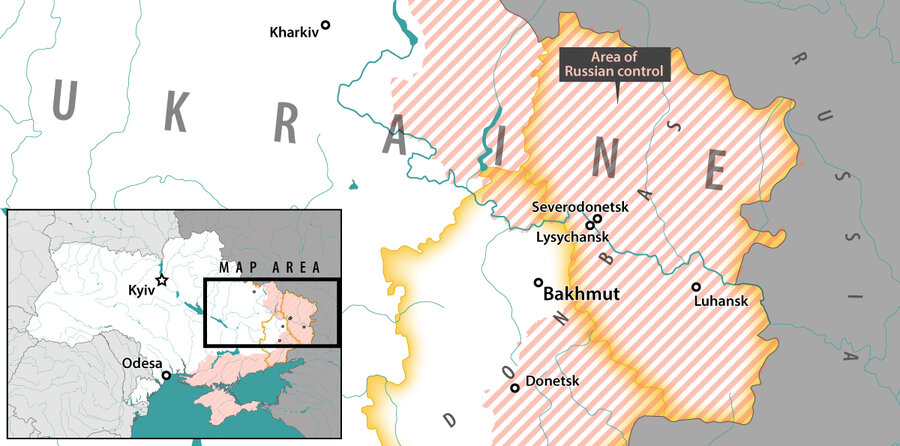

Russian forces are less than 10 miles from Bakhmut, some estimate, though they have advanced little in recent days, since President Vladimir Putin ordered a rest and regrouping after capturing Severodonetsk and Lysyschansk in late June. Over the weekend, Bakhmut was struck by Russian incendiary munitions, which set fire to civilian houses and property. It was one of nearly a dozen towns that Russia targeted across the front-line arc of the Donbas, an industrial heartland of eastern Ukraine that Russia vows to conquer.

“It’s never too late to jump on a last bus with Ukrainian soldiers if they must retreat,” says Mr. Borishpol. “Until then, it’s my home and I believe in the power of the Ukrainian army.”

Despite his calm demeanor, a woman sitting on the back steps of the hostel building reveals the tension, chastising the Chernobyl veteran for speaking to a foreign journalist.

“When the press comes, shelling comes!” she shouts, before angrily standing up and stepping inside.

It is a common refrain of paranoia in this Russian-speaking town, where “normal” has been redefined by the gnawing fear of encroaching conflict. Residents are all too aware of the violence elsewhere, which has left entire cities destroyed by weeks of bombardment.

“I think I should leave,” says Liudmila Krylyshkina, a retired chief engineer with three higher education degrees in finance and law. As she speaks in late June, the ominous sounds of war in the background are constant, like rolling thunder.

“We want to believe that everything will be good. We’re sure that soldiers will protect us,” she says, brushing back gray locks. “We have a strong spirit; they won’t give us up.”

Bakhmut has been struck by Russian ordnance repeatedly, but not yet constantly.

“Those people who have been in places with active bombing, you can see it in their eyes,” says Ms. Krylyshkina. “I would never think we would get to this point, where the war would come.

“It’s become the same as Syria: This is not a war, just killing, a massacring of people,” she says. “How can you imagine people just sleeping in their beds and getting killed? It’s ultra-cruel.”

Two weeks later, contacted by phone, Ms. Krylyshkina says she was unable to leave. Her friend refused to go, and she was afraid to leave on her own. She is now a permanent fixture at the hostel.

Doubts about who’s telling the truth

Across town, in a park with a memorial marking the 10th anniversary of the Chernobyl meltdown, retiree Nelly Rudenchyk sits on a bench in the shade of a purple plum tree and marvels at “how beautifully” swallows are flying as they catch insects.

She lives alone, but says she can’t leave because “you need a pocket with a thick wad of cash, and I don’t have any.” Though she has relatives in Poland, “they don’t need me there,” she says.

Stuck in her mind is a 1960s Cold War song, which became well known in the Soviet Union, called “Say, Do the Russians Want a War?” It describes how sincere Russian intentions were misinterpreted by the West, which Ms. Rudenchyk says she believes is happening today.

She does not watch television because of the “negative energy” it brings, and says she gets her information from those who might randomly sit next to her and talk. She is not concerned if Russian troops seize Bakhmut, because Russians and Ukrainians are “the same” and “someone put us in an argument.”

“I’m sorry for the children who have not been evacuated; they are beginning to stutter,” she says, her words disrupted by the frequent barking of dogs abandoned by those who have fled. Yet she is not convinced that Russia is to blame for this war, or that Russian troops have committed the atrocities verified near Kyiv and across the battlefield since February.

“People make up stuff themselves,” says Ms. Rudenchyk, disbelieving when asked about Russian actions. “I don’t know what’s happening.”

Fully aware of what is happening is Serhii Sobolev, an evacuation driver for a Ukrainian nongovernmental organization called Help People. In late June, his van from Bakhmut had only half a dozen residents seeking safety in cities far to the west.

“Most people who stay, they sit and wait until the very last moment, when shells are falling around them,” Mr. Sobolev said then.

That balance has now tipped, and the charity group in the past week has delivered 50 to 60 tons of food, medicine, and toiletries. Eight vehicles have evacuated 300 people from Bakhmut and other Donbas cities, including Soledar, Sloviansk, and Kramatorsk, where water, gas, and electricity supplies have been cut.

“Now more people are leaving. Buses are full every day,” says Mr. Sobolev, contacted by phone Wednesday.

Not among them is Serhii Pogorelov, a municipal electrician, whose house has been struck by several pieces of shrapnel from an incoming artillery shell. Rockets also smashed into two apartment blocks a stone’s throw down the road, collapsing three floors of one and removing an entire corner of the other.

“This is our land; I was born here,” says Mr. Pogorelov, his fingers stained red from picking cherries. His wife works in a hospital, and he installed the generator in the hostel for those displaced by war.

“No, we won’t change our minds about leaving,” he says. “It’s my house. And we still have a job to do.”

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this story.