In Germany’s east, a hard rethink of relations with once-close Russia

Loading...

| Berlin

Katja Hoyer was 4 when the Berlin Wall fell and Germany was unified into the young republic it is today. Today, the east-west geographical divide in Germany is seen in museum exhibits, but also in the familiarity with all things Russian of eastern Germans of a certain age.

“Many East Germans don’t see Russians as ‘one block of people who follow Putin,’” explains Ms. Hoyer, who recalls visiting St. Petersburg as a girl on a publicly funded trip. “It makes Russians real people as opposed to faceless enemies – it’s more difficult to see people you actually know as enemies.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onHow does one respond when a once-trusted friend turns out to be an aggressive threat to its neighbors? That’s what eastern Germans are wrestling with after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Prior to the Ukraine war, half of eastern Germans wanted closer ties to Russia. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine flipped that sentiment on its head: Now 82% of Germans – including 73% of eastern Germans – see Russia as the biggest threat to world peace in the next few years.

But while the war in Ukraine brought a sudden German foreign policy shift, the affinity for Russia doesn’t disappear overnight, says ethics professor Joanna Bryson.

“Being political opponents and still having a cultural idea of each other has always been the case,” she says. “It’s not a contradiction, even though it sounds contradictory. ... It’s a dialectic that you just endure.”

One of the most widely distributed Russian novels of all time was required school reading for a young Katja Hoyer.

Growing up in East Germany, Ms. Hoyer remembers being impressed by the heroic protagonist of “How the Steel Was Tempered.” The Russian main character, Pavel, was maimed while fighting for the Bolsheviks, and the forging of his character into figurative steel while serving the communists was a “classic Russian socialist novel. You read in Russian about a Russian who’s going through a tough time in their lives,” recalls Ms. Hoyer. It made an impression, as it did on many of her fellow East German schoolmates at the time.

Ms. Hoyer was 4 when the Berlin Wall fell, and Germany was unified into the young republic it is today. Today, the east-west geographical divide in Germany is seen in museum exhibits, but also in the familiarity with all things Russian – including the language, culture, and people – of eastern Germans of a certain age.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onHow does one respond when a once-trusted friend turns out to be an aggressive threat to its neighbors? That’s what eastern Germans are wrestling with after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Many East Germans don’t see Russians as ‘one block of people who follow Putin,’” explains Ms. Hoyer, who recalls visiting St. Petersburg as a girl on a publicly funded trip. “It makes Russians real people as opposed to faceless enemies – it’s more difficult to see people you actually know as enemies.”

Prior to the Ukraine war, half of eastern Germans wanted closer ties to Russia, a desire reflected in the highest levels of leadership. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine flipped that sentiment on its head, galvanizing German public support for Ukraine. Indeed, now 82% of Germans – including 73% of eastern Germans – see Russia as the biggest threat to world peace in the next few years, according to Allensbach Institute research.

Yet a significant proportion of eastern Germans are still struggling to process recent events in light of a decadeslong familiarity with Russia. Just three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this turn of events provides an opportunity to finally close the east-west divide for good, say political experts.

“Snobbery toward [eastern Germans] is certainly a huge problem. Surveys suggest two-thirds feel they are treated as second-class citizens,” says Ms. Hoyer, now a German British journalist and visiting fellow at King’s College in London. “Now we have the first generation of unified Germans, who never experienced the divide between East and West as an existential threat to their own state. Perhaps there’s a chance to try to bridge those differences.”

“Big brother”

Germany has a deep, complex relationship with Russia, marked by periods of cooperation as well as conflict. In modern times, most impactful to ties between the two countries has been the devastation of World War II, during which the Soviet Union lost more than 26 million people amid Nazi Germany’s brutal campaign in the country. The ensuing formation of East Germany as a socialist state and Soviet satellite then steeped generations of Germans in Russian language, culture, forms of government, and art.

“You learned Russian, you knew Russian literature, you sang Russian songs,” says Judith Enders, an eastern German political historian who teaches at the Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin. “As little GDR, you always had to do what big brother said, and sometimes big brothers are nice and protective, and sometimes they’re really mean.”

Dr. Enders recalls childhood memories such as student exchanges in Russia, Russian soldiers throwing candies to East German children, and feelings of the Soviet Union being a provider of opportunities in education and life.

“For children also, the Soviets built the space station, and to me that was peace and community,” says Dr. Enders. “These are all the things that scurry around in the back of the East German mind from childhood. It’s a background melody. From all of this, the relationship to Russia is then fed.”

While West Germans were more familiar with U.S., French, or British culture, East Germans were more likely to know Russians personally than Americans or Britons. For a certain generation of East Germans – who today comprise 16 million of Germany’s 84 million people – Russian nostalgia runs strong.

While the war in Ukraine brought a sudden German foreign policy shift, the affinity for Russia doesn’t disappear overnight, explains Joanna Bryson, an ethics professor at the Hertie School in Berlin.

“One of the things societies do is that they entertain lots of different ideas and identities, building up multiple conflicting models about the way the world is going,” says Dr. Bryson. “Germany has been one of the strongest voices saying no one is redrawing the lines of Europe ever again. That was a very strong line of thought and peace. And with Ukraine you suddenly realize, ‘No, we are not protected.’ Suddenly Germany is arming for war to defend the peace.”

In other words, society will take time to catch up with policy. Further, says Ms. Enders, all the European cultures are like “one family.”

“Borders are always pushed back and forth,” says Dr. Enders. “Being political opponents and still having a cultural idea of each other has always been the case. It’s not a contradiction, even though it sounds contradictory. That’s harder to understand in America, because cultural identity is very fixed on the United States and the Constitution and on independence. But in Europe these stories are much longer and older and interwoven. It’s a dialectic that you just endure.”

Indeed, the heads of Germany and Russia for decades not only read each other’s literature and appreciated one another’s arts and music, but also spoke each other’s languages.

Russian President Vladimir Putin speaks German and worked in Dresden for a time in the 1980s as a member of the KGB, and had a close relationship with Gerhard Schröder, the former German chancellor. Mr. Schröder’s successor, Angela Merkel, was raised a pastor’s daughter in East Germany, and her language skills were so fluent she won the country’s Russian-language Olympiad. Later, as chancellor, she increased Germany’s dependency on Russian energy supplies and extended ties in other ways.

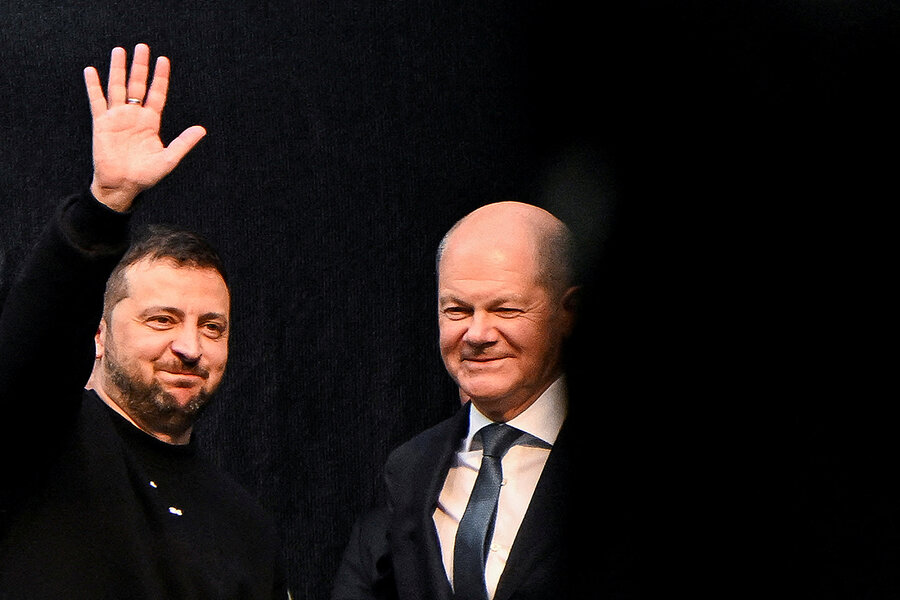

Current German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, when a young law student, was a socialist activist who worked with East German communist youth leaders to help block the U.S. from placing nuclear missiles in Europe. His political orientation then was closer to the Soviet Union’s than America’s.

This and other sentiments can be wrapped up in what researchers call a German “affinity-guilt complex” toward Russia, developed in the aftermath of World War II and the actions of a German dictator which left tens of millions of Soviet soldiers dead and devastated large parts of Eastern Europe and Russia. Germany’s longstanding history and cultural affinity for Russia complicates the country’s public position in a way that U.S. politicians needn’t grapple with when it comes to public opinion around arming Ukraine.

A chance to reengage

As the war drags on, the potential for the decline of German support for Ukraine persists. Yet at the same time, there’s an opportunity. Prior to Mr. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, half of eastern Germans wanted closer ties to Russia, compared with only a quarter of their western German counterparts, according to a 2021 study.

But now there are signs that eastern German support may be ebbing, which presents an opportunity to reengage such easterners, who tend to identify with far-left or far-right parties, if they vote at all.

Ms. Hoyer, the journalist, points out the need to bring this segment of the population more fully into the fabric of German society and culture. What’s pervasive in German culture is a certain western snobbery toward the east, she says.

“In 2000 when I traveled to [parts of western Germany], people were still asking questions like ‘Do you have running water now? Are there cars? Are there roads?’” she says. “There was a very strong narrative in the West about what it was like in the East, and people haven’t really dispelled those myths, that all East Germans were passively subjugated by the state and weren’t able to develop at all economically.

“That’s still very much still there.”