French women flock to Gisèle Pelicot rape trial, ‘to show her that she’s not alone’

Loading...

| Avignon, France

Since it began in September, the rape trial of Dominique Pelicot has captivated and outraged the French. But here in Avignon, where the case is being prosecuted, the trial has touched a nerve with local women.

Every day for the past three months, supporters have woken up early, taken time off work, and dedicated their off days to come here to the Avignon courtroom. They sit in silence, listening to often gruesome testimony.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe Pelicot rape trial is not just drawing the attention of French media. The courthouse has become a gathering place for people, especially young women, seeking to support Gisèle Pelicot and the change they see her standing for.

That is by the request of Gisèle, Mr. Pelicot’s wife, whom he is accused of drugging with sleeping pills and raping for a decade. He is also charged with recruiting dozens of other men to rape her while he watched and recorded them. She wants her case to serve a larger purpose: to shift the shame surrounding rape onto the accused.

“I came here to support Gisèle, to show her that she’s not alone,” says Alison Pradel, a law student from Nimes. “Rape can’t be hidden in the shadows anymore.”

“It’s definitely something different to be here in person,” says Mathilde Portail, who took an hourlong train from Montpellier after work one day to see the trial for herself. “The number of people who have come to be here with Gisèle, and the signs around town – you can really feel the support.”

It’s 9 a.m. and court is in session. Inside the overflow room – a makeshift space set up for the public – a video feed blares proceedings from the main courtroom. A petite woman in all white calls this small, 60-odd crowd to order. There’s no talking allowed, no cellphones, and no food or drinks. During the break, those inside must leave so that those in the long line outside the door can get a chance to watch the trial.

“If you get up to use the bathroom,” she says, “you lose your spot.”

Across the hallway in the main courtroom is Dominique Pelicot, sitting slack-jawed and downtrodden. But this crowd of mostly women is not here to see him. They’re here to support Gisèle, his wife, whom Mr. Pelicot is accused of drugging with sleeping pills and raping for a decade. He also recruited dozens of men to rape her while he watched and recorded them.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe Pelicot rape trial is not just drawing the attention of French media. The courthouse has become a gathering place for people, especially young women, seeking to support Gisèle Pelicot and the change they see her standing for.

Since it began in September, the Pelicot trial has captivated and outraged the French. But here in Avignon – and nearby Mazan where the rapes took place – the trial has touched a particular nerve with local women, with something resembling fandom for Ms. Pelicot.

Every day for the past three months, supporters have woken up early, taken time off work, and dedicated their off days to come here to the Avignon courtroom. Some come every week. For others it’s their first time. Most live within an hour of Avignon, but all have given up their day to be here.

They sit in silence, listening to often gruesome testimony from the lawyers of Mr. Pelicot and the 51 accused, and watching Mr. Pelicot’s rape videos that the trial has made public. That is by the request of Ms. Pelicot, who wants her case to serve a larger purpose: to shift the shame surrounding rape onto the accused.

“I came here to support Gisèle, to show her that she’s not alone,” says Alison Pradel, a university law student from Nimes, around 45 minutes away, who has come twice to court by herself. “To see her in person made it more concrete, more real. By making her case public, everyone can see what happened. Rape can’t be hidden in the shadows anymore.”

Mathilde Portail says she took an hourlong train after work one day in late November to see the trial for herself, after being “filled with anger” while reading about the trial from her home in Montpellier.

“It’s definitely something different to be here in person,” says Ms. Portail, during an hourlong wait in the security line to get into the courthouse. “The number of people who have come to be here with Gisèle, and the signs around town – you can really feel the support.”

Controversy in the community

A few steps from the courthouse is Avignon’s famous walled old city. Inside those walls, local feminist organizations have plastered signs of support for Ms. Pelicot, like “Rape is rape” and “Gisèle: Women thank you.”

But there is a palpable tension when court gets out of session. At Bar La Brasserie, a local restaurant, the owner says he recently decided to stop serving trial defendants who were regularly coming in during the lunch break because he “didn’t feel right about it.”

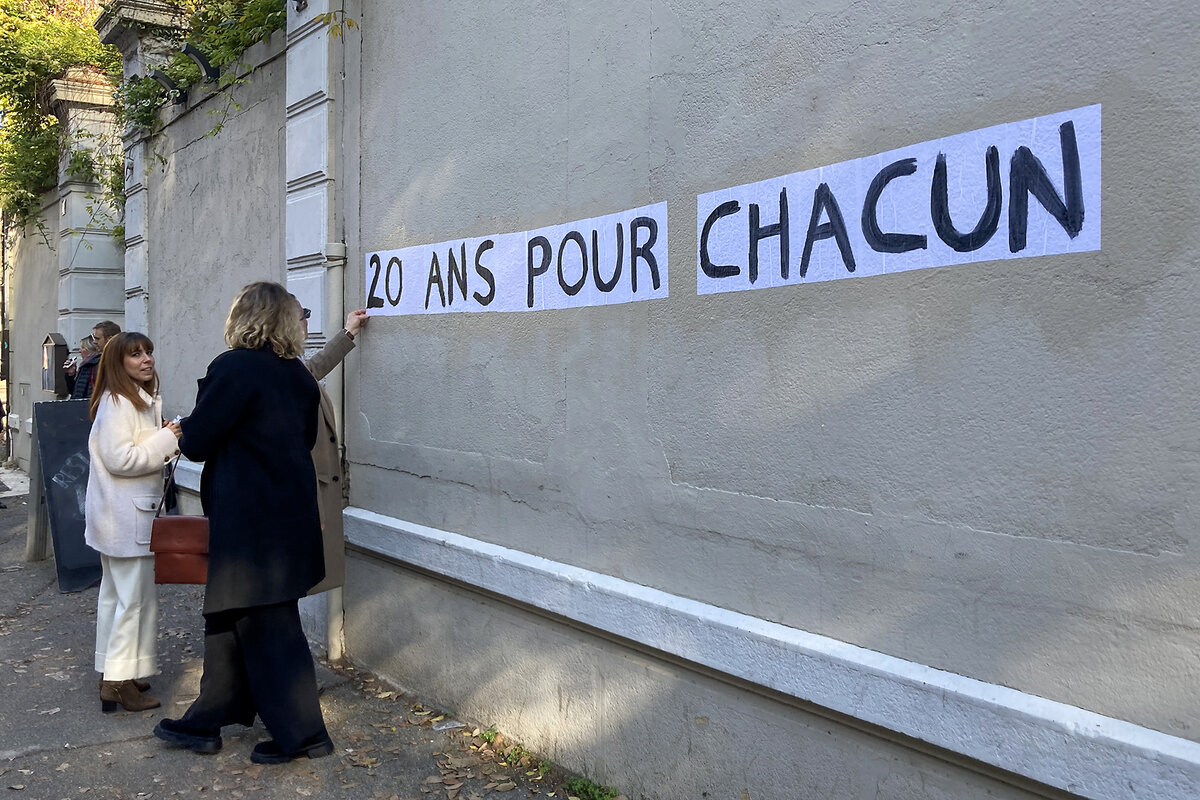

Across the street, three lawyers for the accused men – including two women – scrape off the “2” in “20 years for each.” Similar protest signs have been plastered around town, calling for 20 years of prison for each of the 51 accused, instead of the four to 18 that prosecutors are calling for.

Some of these men will never interact with the public. At least a dozen with previous convictions are held in court during breaks and at the end of each day are packed onto a prison bus. But the rest are free to walk around, have lunch in local restaurants, and chat in the courtroom lobby.

On a late November day, two of the accused wear pandemic-era masks, sunglasses, baseball caps, and hoodies as they enter court. But most don’t try to hide their faces and a majority are what the French press have dubbed, “Monsieur Tout le monde,” or “Mr. Everyman.” Indeed, among the list of the accused is a firefighter, a soldier, a journalist, and multiple farm workers; they’re of varying ages, ethnicities, and social backgrounds.

Most lived within a 35-mile radius of the Pelicots, in the small town of Mazan. That has put only a few degrees of separation between locals and the accused. Until now, Mazan was a quaint village of 6,000, known for its wine, fruit, and truffles. Now, it is being referred to as “the village of rapists.”

“Honestly, it defies comprehension. It’s like something out of science fiction,” says one bespectacled man at local Mazan restaurant called Le Siècle, who asked to remain anonymous. Like many residents here, he is tired of talking about the trial. “All I can think about is my two daughters. What if something like that happened to them?”

Gisèle Pelicot, feminist hero

When court gets back into session in Avignon, some of the women who attended the morning hearing are back in the line, hoping to get in to see this landmark trial. Others are here for the first time, like Margaux Oren, who took the train from Marseille with a friend to support Ms. Pelicot.

“It’s a historic moment,” says Ms. Oren, who has participated in feminist protests related to the trial. “I hope it’s going to bring rape culture to light. But it would be nice to see more men out here in support.”

Dominique Pelicot’s lawyer, Béatrice Zavarro, says that even if she feels like “the devil’s advocate,” gender didn’t play a role for her in deciding whether or not to take this case. In fact, during a break from court, she says she’s received an outpouring of female support “for bringing justice to victims of sexual violence while defending Dominique.”

Last month, French Equality Minister Salima Saa unveiled several measures to combat sexual violence against women. On French radio in mid-November, she said there will be “a before Mazan and an after Mazan, just like there was a before and after #MeToo.” The verdict is expected on Dec. 20.

The Pelicot trial appears to be a watershed moment for France. And for French women, Ms. Pelicot is their feminist hero.

“One day, Gisèle walked by me after court. I went up to her and just said, ‘Thank you,’ and, ‘We’re all here for you,’” says Avignon local Maguelonne Courbet, who has attended the Pelicot trial court proceedings four times. “She looked at me with tears in her eyes. It shook me to the core. I still get chills thinking about it.”