Rising global food prices squeeze the world's poor

| New Delhi

Amid the stalls of neatly stacked vegetables at this city's Sarojini Market, Manju shops with her young granddaughter. Her bags have become lighter in recent months, as she's cutting back on the basics. Food prices have risen sharply over the past year and Manju is even going with fewer onions, the ubiquitous ingredient that fills just about every Indian gravy dish.

"The kids have stopped eating properly," she says. "They have lost the taste for food and are complaining."

Families in many parts of the world – especially India, China, Mexico, Haiti, and Egypt, where food costs spiked in the past year – are making sacrifices and seeking alternatives.

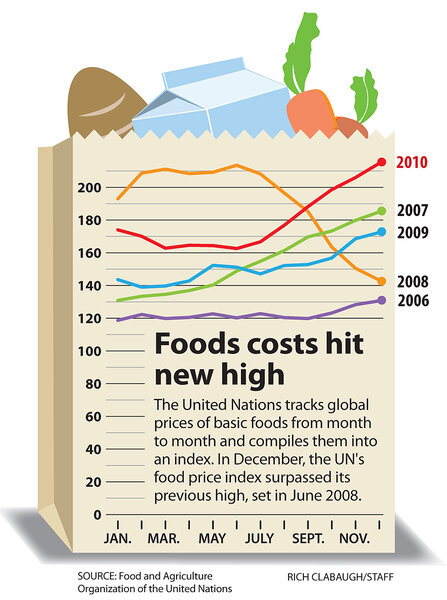

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) food price index hit an all-time high in December. This sparked concern that high prices just prior to the global recession could reflect longer-term structural changes in supply and demand that will imperil the poor's ability to eat.

Before the latest rise, Gallup surveys from 2009 painted a picture of 1 billion people worldwide who struggle to afford food. It's too early to tell if higher costs will dramatically add to those ranks of the world's hungry. But it's clear that all around the world – where food is growing more expensive due to weather shocks, export bans, inflation, high oil prices and biofuels, speculation, and slowing growth in farm yields – many are going with less.

Cutting corners in China

As a retiree eking out his pension with a part-time job, Zhao Zongya is used to being frugal. But with food prices continuing to rise in China, he says he has to cut more corners to feed himself, his wife, and his mother.

“When prices go up, the only solution is to buy less or to stop buying unnecessary things,” says Mr. Zhao, who lives in the port city of Tianjin.

Eggs have nearly doubled in price recently, “so we buy fewer eggs,” Zhao says regretfully, and apples have soared beyond his price range. “We’ve just stopped eating apples.”

Zhao has also adopted a tactic used around the world by poor people: He goes to the market just before it closes, so as to get a better price on food that the stall-holders want to unload. Or he visits his local supermarket as soon as it opens, when he can still find overnight vegetables that are sold more cheaply.

Until a few months ago, Zhao recalls, he spent about 800 RMB ($120) a month to feed his three-person household. Now he needs another 300 RMB ($45). Even though the government raised his pension this month, “it’s not enough to cover the price rises,” says Zhao.

Starvation is a thing of the past in China. Only 10 percent of the population was hungry in 2007, down from 18 percent in the early 1990s, according to the FAO. Many Chinese have seen incomes rise, offsetting higher food bills to some degree. In 2008, a year with high food prices before the global economic crisis, the Gallup percentages of Chinese, Indians, Vietnamese, and Indonesians who said they had trouble affording food went down, not up, points out Derek Headey, an economist with the International Food Policy Research Institute.

"This is partly because these countries insulated their domestic markets from international price rises, and partly because they were all experiencing rapid economic growth," says Dr. Headey.

Because those countries make up so much of the world's population, those previous increases may not have added to food insecurity overall. This time, however, China, India, and other large countries like Brazil are seeing rapid food inflation. "So there is a strong possibility that unless food prices improve soon, the 2010-11 crisis could actually be much worse than what we observed three years ago," he adds, referring a similar spike in the FAO's food price index.

Corn tortilla prices rise in Mexico

While American farmers' productivity underpins global food supplies, some US policies are linked to recent surges in food cost, particularly in Mexico, where corn prices have jumped. Many economists have fingered the diversion of American cropland to biofuels, particularly corn-based ethanol, as a major stressor.

Isabel Gutierrez, a homemaker from Ecatepec on the outskirts of Mexico City, says she walks half an hour down a teetering hill in search of cheaper food. Corn tortillas have climbed to 10 pesos (83 cents) from 7 pesos (58 cents) a few months ago in her poor neighborhood. “Sometimes you don’t buy because you just don’t have the money," she says.

Mexico's National Policy and Social Development Evaluation Council (Coneval) estimates that the percentage of the population that cannot afford basic food items rose around 20 percent between 2008 and 2010. Experts say this has more to do with the global economic crisis than food prices, but it's a reminder that this cost increase – unlike the previous one – comes on the heels of an economic downturn.

While Mexico is subsidizing farmers and tortilla suppliers in an effort to boost production, such internal controls are less available to countries like Haiti, which have fewer funds and a less-developed agricultural sector.

At the mercy of global markets

Three decades of the US flooding Haiti's markets with surplus from its heavily subsidized farming industry has decimated Haitian agriculture. The International Monetary Fund has brought tariffs on rice down from 35 to 3 percent over the past 15 years, benefiting US agribusiness but leaving Haitians like Ines St. Martin more at the mercy of global food prices.

Ms. St. Martin scrapes a living selling used clothing imported from the US from a labyrinthine market in Port-au-Prince. Her husband died and she has eight children to feed. “Today, prices for things are steep, but we’ve no choice but to make do with what we have,” she says. She tries to make the meals by cutting corners, using corn and rice rather than potatoes or meat. “It’s impossible to make the complete meal with what I earn, so we all eat a bit less.”

According to the World Food Program, between 2.5 and 3.3 million Haitians are estimated to be “food insecure.”

Subsidies in Egypt

In Egypt last May, the government painted a sobering picture of food prices: In the previous year, vegetables rose 45 percent, fruit by 26 percent, sugar by 23 percent, and dairy products by 8.5 percent.

Egypt spends billions annually on food subsidies, and in 2008, due to soaring food prices, it expanded the subsidy program by 15 million people, bringing the number of beneficiaries to 80 percent of the population.

Still, buying food can be a struggle. About 5 million to 6 million Egyptians in 2008 were considered food insecure. "Look at us – we're not healthy. It's not good to avoid fruits and vegetables. But I have no choice," says Fatima, a single mother who cares for two sons and her elderly father.

Fatima earns about $8.50 a day cleaning homes. Feeding her family is difficult, and has only gotten harder in the past few years as food prices have steadily climbed. And yet she’s better off than the 40 percent of Egypt’s 80 million people who live on less than $2 a day. On a recent shopping trip, for instance, zucchini squash, a staple of Egyptian dishes, was too much for her budget. Instead she bought molokheya, a leafy green used in soup. Beef is out of reach.

“My family never eats beef,” she says. “We can’t afford it, ever. So we eat fish, and sometimes chicken if it’s not too expensive. And we eat beans.”

Fatima says she often resorts to filling yet cheap carbohydrates and legumes to make sure her sons fill their bellies. Rice, macaroni, lentils, and beans often take the place of meat and fresh fruits and vegetables, she says. She rarely buys fruit.

“The prices have gotten so high that we eat whatever will keep us alive, and disregard our health in the process,” she says.

An Evergreen Revolution?

In India, there's a bit of good news. Onion prices that had quadrupled over the past few months – and sparked a protest in the capital – have fallen. Prices shot up after India's monsoon came late and heavy, damaging the crop. India prevailed on rival Pakistan to boost onion exports by threatening to cut off its tomato exports to Pakistan.

David Dawe, a senior economist with the FAO, says short-term spikes in food prices aren't as concerning as the long-term questions about where food prices are headed, especially as agricultural land and water become scarcer.

But he remains optimistic about improvements in the supply side of the equation. Indeed, President Obama has been pitching agricultural collaborations with developing countries to research higher-yield seeds and teach resource conservation.

On his recent trip to India, Mr. Obama and his counterpart, Manmohan Singh, pledged to embark on an "Evergreen Revolution" designed to expand Indian farm production in a sustainable manner.

This would be done by supporting Indian efforts to target regions where the first Indo-US partnership in the 1960s and 70s known as the Green Revolution never fully succeeded. This first revolution introduced higher yield seeds as well as expansion of mechanization and chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

But, the Evergreen Revolution would also pour more money into new research and development – led by the US but shared with Indian institutions.

“The USA is the leader, in terms of its agricultural university system,” says Mukesh Khullar, joint secretary of India's National Food Security Mission. “Whether these [new technologies] are accessible to us or not is an issue on which there should be strategic partnerships and that’s what Obama has done with us.”

The US, meanwhile, gets a chance to try out research innovations in India before passing along to other developing countries, says Mr. Khullar.

Part of this next generation technology could be transgenetic crops, says Khullar, such as rice crops that need less water but are created partly with a non-rice gene. Such technology has proven controversial, acknowledges Khullar.

“All those [safety] protocols will have to be assured,” he says. But the innovations are necessary. “You need it for ensuring that food is produced in adequate quantities.”

• Includes contributions from Peter Ford and Zhang Yajun in Beijing; Isabeau Doucet in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Nacha Cattan in Mexico City; and Kristen Chick in Cairo.