Changing foreign aid: can more groups 'buy local'?

Loading...

| Yangon, Myanmar; and Chingola, Zambia

A reformist government and an easing of sanctions mean that Myanmar (formerly Burma), a former pariah state in Western eyes, is increasingly open for business.

But as Western investment and aid start flowing into this once-isolated nation, many wonder if its companies – many of which have never faced foreign competition, let alone worked with a global organization – will get a piece of the action.

Part of that will depend on whether foreign organizations "buy local."

It's a phenomenon hardly limited to Myanmar. With billions of dollars in aid and development money pouring into emerging economies from Southeast Asia to sub-Saharan Africa, host governments are pushing organizations to source vegetables, mining equipment, and other products from local firms. It's a way to ensure that local entrepreneurs – not just foreigners – benefit from investment. Local businesses create jobs and spread knowledge in poor countries that often lack both.

Yet while some local companies in these developing nations can meet the standards demanded by international organizations, many cannot. Some foreign companies, confronted with pressure to source locally, have left altogether – such as Wal-Mart, which withdrew from India in October over a dispute about buying locally, taking its promise of jobs and investment with it. In Zambia, the chief executive of the largest private employer – a foreign company – had his visa revoked after the company dropped local contractors.

The debate has ramped up in the wake of the Philippines typhoon, as Western aid agencies such as the US Agency for International Development face calls to buy more of their supplies in or close to the countries where they're operating. (See story, page 20.)

As a result, there's a movement of entrepreneurs trying to bolster their credentials to attract the notice of international organizations.

Training local entrepreneurs in Myanmar

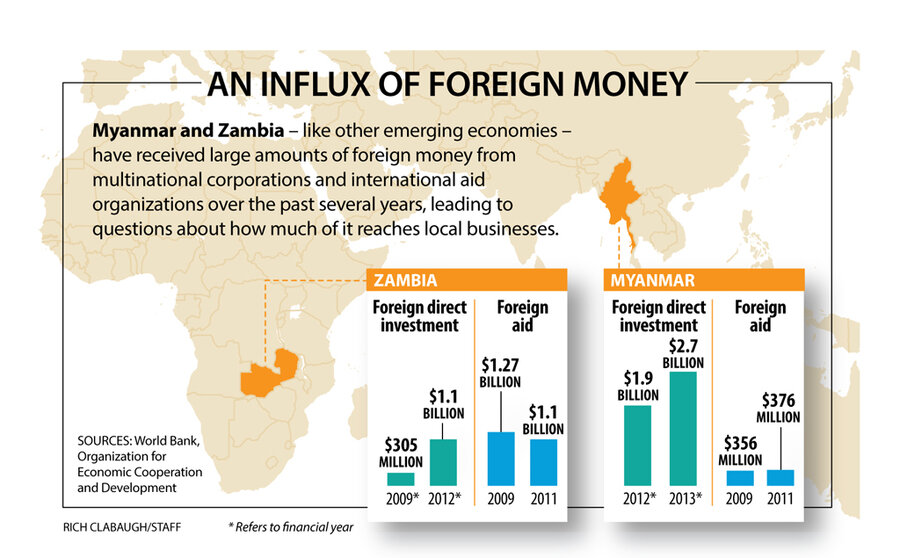

In Myanmar, where foreign investment increased from $1.9 billion in 2011-12 to $2.7 billion in 2012-13, the current influx of foreign money is "both an opportunity and a risk," said Ye Thu Aung, managing director of Vivo, a local food distribution company, as he met recently with a team from Building Markets, a US-based nonprofit that promotes local sourcing in the foreign-aid industry, in his office in downtown Yangon's bustling Chinatown district.

Next to a small golden Buddha surrounded by blinking lights, Building Markets' employees jotted down the details of Mr. Ye Thu Aung's business operation for their database, which links small and mid-size companies to foreign organizations, such as the United Nations or Western aid agencies, looking to buy goods.

While local companies may lack size and resources, they bring a better understanding of the local and regional economy, says Scott Gilmore, a former Canadian diplomat who founded Building Markets in 2004. His organization focuses on harnessing that potential by making entrepreneurs aware of procurement opportunities, and has trained more than 300 local firms to bid on contracts – for items such as hospital stretchers – since arriving in Myanmar last year.

"Local entrepreneurs are far more capable than outside observers realize," says Mr. Gilmore during a recent visit to Myanmar. "[The question is] how do we assist local entrepreneurs in seizing those opportunities?"

Flow of foreign money

More than $700 billion in foreign direct investment flowed into developing countries in 2012 – making up 52 percent of total global FDI – according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development. While foreign companies often bring in specialized expertise and technology and create jobs, the perception on the ground also includes concerns that foreign firms will hurt local companies.

Official foreign-aid funds flowing to the developing world are dwarfed by the money coming from foreign investment and remittances – making it important that local companies secure contracts on the commercial side, not just the aid sector.

Several Asian and African nations that enjoy rising interest from foreign companies have put in place "local content" regulations to assuage concerns from local businesses. In late November, Ghana's Parliament passed local content laws for the country's oil industry. Foreign firms often find those laws too restrictive. Myanmar's huge neighbor to the west – India – saw Wal-Mart in October scale back a long-planned expansion. Wal-Mart said it could not abide by an Indian requirement that foreign supermarkets buy 30 percent of their products from local industries – a law put in place in 2012 to ensure that local firms don't get crowded out by foreign competition.

Sometimes foreign firms in emerging markets favor their home-country suppliers, or just don't know local options are available.

Take Zambia, the copper king of Southern Africa. President Michael Sata, who was elected in 2011 on populist promises to spread the wealth of mining investment, has been putting political pressure on foreign mining companies to give contract business to Zambian companies.

"I know a story of a mine importing sand from South Africa when there is so much sand in Zambia," said Miles Sampa, deputy minister of Commerce, Trade, and Industry at a Sept. 19 industry meeting in Kitwe. "On top of that, some of them don't even create employment because they bring in foreigners to dig the copper."

Joy Sata, public relations manager at Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), Zambia's largest private employer, says local contractors can't fulfill all of her company's needs. "There are some contracts that are better done by international contractors because of things like expertise and equipment," she says.

After KCM ended some local contractors' agreements several weeks ago and announced plans to lay off more than 1,500 workers, Zambia's government revoked the chief executive officer's work permit.

Reginald Mubanga, a business banker and consultant at Stanbic Bank Zambia in Chingola, notes that some local companies, such as beef and poultry producer Zambeef, which is now listed on the London Stock Exchange, have developed good partnerships with foreign companies.

But in Zambia, he argues, those companies are still the exception. "One, they cannot meet international standards of doing business – just writing a proper business proposal is a big problem to many of them," Mr. Mubanga says.

Bidding for economic opportunity

The bidding process is where Building Markets is focusing most of its efforts in Myanmar, employing a model it's also used in Mozambique, Afghanistan, Liberia, Haiti, and East Timor over the past decade.

It's targeting the vast, $125 billion international aid and development sector, which is ramping up activity in Myanmar two years after a military junta ceded control to a quasi-democratic government.

"It makes sense to try to use procurement to build economic opportunity in the target countries" despite the complexities involved, says Todd Moss, senior fellow and vice president at the Center for Global Development, a Washington think tank.

Building Markets' Gilmore argues that it's vital for local companies to become part of the foreign-aid pipeline now, while donors and agencies are still making their plans.

Myanmar has a particularly complicated set of dynamics for foreign investment and aid, given that many elite families who dominate the economy are on a US Treasury Department blacklist, putting them off limits for American firms and organizations. But other companies in Myanmar face more pedestrian obstacles, such as workers with low skill levels and a lack of computer skills, and a shortage of electricity.

Gilmore worked as deputy national security adviser of the UN peacekeeping mission in East Timor in 2001, after it broke away from Indonesian rule. He says he went back to his house every day "demoralized" about the lack of effect all the aid money flowing in was having in the war-torn country.

But he noticed that his landlord was using the rent Gilmore paid him to create a busing company – which, in turn, inspired Gilmore to start his nonprofit.

"At the end of the day, poverty is reduced by a job," Gilmore says. "What [an entrepreneur] needs is a contract."