The international politics behind Obama's Nobel Peace prize

Loading...

STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN; and BOSTON -- The surprise decision to award President Barack Obama the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize had much of the world scratching its head on Friday, even among the president's most ardent fans. Less than a year into office, the young president has made lofty promises, committed his administration to diplomacy, and convinced the world that a less belligerent America is in the offing.

But he is also the commander-in-chief for the Afghan and Iraq wars, as well as ongoing lower-scale US military efforts in Pakistan, the Horn of Africa, and the Philippines. Later on Friday, Obama will hold a strategy session with his war cabinet that could lead to a commitment of more combat troops to Afghanistan. A commentator on Britain's Sky News captured the mood well when he said it appeared Obama had won the prize for "not being George Bush."

America's international standing was at a nadir by the end of the Bush administration, and Obama's decision to negotiate with Iran over its nuclear program (already bearing some fruit) and promises to reinvigorate US efforts in Israel-Palestinian peacemaking have quickly remade America's international image, with the US leaping into the top spot in a recent survey on the world's most admired countries. That's especially so in Europe, where Obama's decision to cancel a planned missile-shield system in Eastern Europe that had rankled Russia has been widely praised.

And the five-member Norwegian committee that picks the annual peace-prizewinner clearly has something more in mind than simply giving Obama a $1 million high-five for being such a popular guy. Unlike the other Nobels, which are given for a lifetime of generally indisputable high achievement in areas like physics, chemistry, and literature, the peace prize has often been awarded more in hope than hindsight -- and with an eye to nudging world events.

Political Impact

The 1996 award of the peace prize to Cardinal Carlos Belo and politician Jose Ramos Horta -- both prominent campaigners for East Timorese independence from Indonesia -- put a spotlight on their cause and helped create the conditions that led to Indonesia's pullout from the country in 1999. Mr. Horta, at the time, was serving as the spokesman for Fretilin, an armed group that waged a 20-year insurgency for independence.

The controversial awarding of the 1994 prize to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzahk Rabin, Foreign Minister Shimon Peres, and Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat was less successful. Though the three men eventually signed the Oslo Accords that seemed to have the two nations on a path toward peace, that effort eventually broke down. All three men could be said to have blood on their hands from that conflict, and Mr. Arafat died without achieving his dream of an independent Palestinian state. Mr. Rabin was assassinated in 1995 by an Israeli furious that he was negotiating land concessions.

So what is the Nobel committee after in this case? Gro Holm, the senior commentator on foreign affairs at the Norwegian Broadcasting Corp., says that the prize committee was probably trying both to ratify Obama's immense international popularity and put pressure on him to deliver on the promise of greater international peace and stability.

"You can't overlook the fact that Bush was hugely unpopular here, and that Obama has turned that trend around," says Ms. Holm. "My 14-year-old daughter was up all night watching election returns because of Obama."

Middle East Focus

She says Obama's plan to scrap the missile shield was a "symbolic step" that "calmed down the Russians" and earned him praise in many European capitals, but also says the award was given, more than anything, to push Obama toward what the committee hopes he can achieve. "There is a feeling here that this is a risk. What does it say about the award if progress isn't made? I think Obama is a deeply moral man, and this seems designed to remind him of his promises."

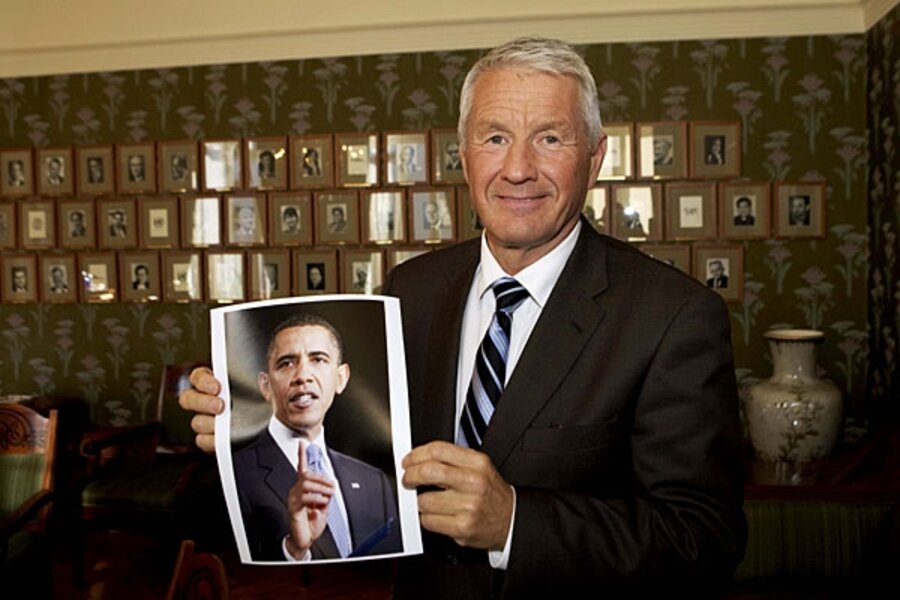

She also points to Thorbjorn Jagland, a former prime minister who was appointed earlier this year to head the committee by the Norwegian parliament, as an important player in delivering the award to Obama. Holm says Mr. Jagland has an activist vision for the Nobel as a prize that can spur peace, rather than simply reward its achievement. "He likes to play big games, he's very ambitious, and this will give him a platform,'' she says. "He'll get to meet Obama and have some influence if he comes to accept the award."

Erling Borgen, a Norwegian documentary filmmaker and journalist who focuses on human rights issues, said Jagland's appointment was controversial in Norway, since his deep political involvement had some worried that the committee's reputation for evenhandedness would be compromised.

"Criticism of [Jagland] is really picking up after this announcement. He had a lot of influence over the decision,'' says Mr. Borgen. "The Nobel Committee is supposed to be completely independent and nothing to do with the Norweigan parliament. But Jaglund has been prime minister, minister for foreign affairs and president of the parliament.”

Jagland, on the left side of Norwegian politics, is deeply interested in Middle East peace. He was one of the five members of the commission led by George Mitchell in 2000 that led to the creation of the so-called "road map" for peace that is still the framework for ongoing negotiations. Mr. Mitchell, a former US senator, was named Obama's Middle East envoy earlier this year.

Announcing the award, Jagland insisted that we "are not awarding the prize for what may happen in the future, but for what he has done in the previous year" and praised Obama for going "to Cairo to try to reach out to the Muslim world, then to restart the Mideast negotiations, and then he reached out to the rest of the world through international institutions."

Jagland, like Obama, is a big fan of international institutions - he once nominated the European Union for the Nobel Peace Prize. Yet while Obama's speech to the Muslim world in Cairo has been widely praised, Palestinians and other Arabs have been grumbling of late that they were empty words with limited follow-through.

Jagland seemed to hint at this in his further comments, when he addressed the political intent behind the award. "We are hoping this may contribute a little bit for what he is trying to do.... [The prize] is a clear signal to the world that we want to advocate the same as he has done to promote international diplomacy."

Martin Indyk of the Brookings Institution in Washington, writes that the atmospherics behind the award are politically useful for Obama. "Winning over world opinion, which the Nobel prize award signifies, can help. It frees up governments to respond positively to Obama's call for them to assume their responsibilities. And that in turn puts pressure on rogue leaders to mend their ways and join the developing international consensus," he wrote. "But if it turns out that George Will is right and Obama ends up being "adored but ignored" then the Nobel committee will have done him no favors."

Borgen argues that rewarding Obama now devalues the Nobel. “It’s too early to award a peace prize to a president who has only been working eight months and has really done nothing for peace,” he says. “A president who plans to send 40,000 soldiers to fight a war in Afghanistan should not be given the Nobel peace prize especially given that the numbers of civilians being killed is at the same level as it was under George W. Bush."