Dead Sea Scrolls to get 'Google' treatment

Loading...

| Jerusalem

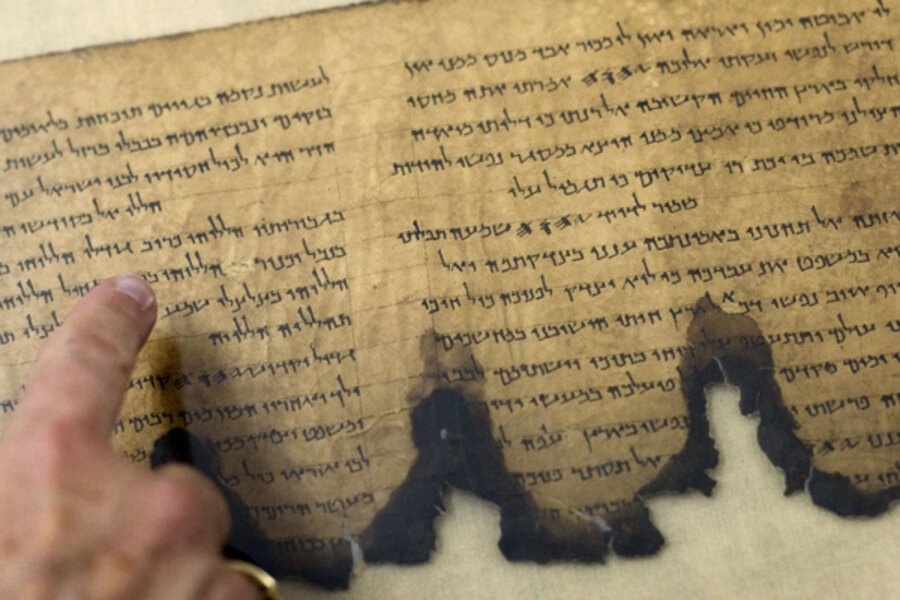

The Dead Sea Scrolls, among the world's most important, mysterious and tightly restricted archaeological treasures, are about to get Googled.

The technology giant and Israel announced Tuesday that they are teaming up to give researchers and the public the first comprehensive and searchable database of the scrolls — a 2,000-year-old collection of Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek documents that shed light on Judaism during biblical times and the origins of Christianity. For years, experts have complained that access to the scrolls has been too limited.

Once the images are up, anyone will be able to peruse exact copies of the original scrolls as well as an English translation of the text on their computer — for free. Officials said the collection, expected to be available within months, will feature sections that have been made more legible thanks to high-tech infrared technology.

"We are putting together the past and the future in order to enable all of us to share it," said Pnina Shor, an official with Israel's Antiquities Authority.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the late 1940s in caves in the Judean Desert and are considered one of the greatest finds of the last century.

After the initial discovery, tens of thousands of fragments were found in 11 caves nearby. Some 30,000 of these have been photographed by the antiquities authority, along with the earlier finds. Together, they make up more than 900 manuscripts.

For decades, access to 500 scrolls was limited to a small group of scholar-editors with exclusive authorization from Israel to assemble the jigsaw puzzle of fragments, and to translate and publish them. That changed in the early 1990s when much of the previously unpublished text was brought out in book form.

But even now, access for researchers is largely restricted at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where the originals are preserved in a dark, temperature-controlled room.

Shor said scholars must receive permission to view the scrolls from the authority, which receives about one request a month. Most are given access, but because no more than two people are allowed into the viewing room at once, scheduling conflicts arise. Researchers are permitted three hours with only the section they have requested to view placed behind glass.

Putting the scroll online will give scholars unlimited time with the pieces of parchment and may lead to new hypotheses, Shor said.

"This is the ultimate puzzle that people can now rearrange and come up with new interpretations," she said.

Scholars already can access the text of the scrolls in 39 volumes along with photographs of the originals, but critics say the books are expensive and cumbersome. Shor said the new pictures — photographed using cutting-edge technology — are clearer than the originals.

The refined images were shot with a high-tech infrared camera NASA uses for space imaging. It helped uncover sections of the scrolls that have faded over the centuries and became indecipherable.

If the images uploaded prove to be of better quality than the original, scholars may rely on these instead of traveling to Jerusalem to see the scrolls themselves, said Rachel Elior, a professor of Jewish thought at Jerusalem's Hebrew University.

"The more accessible the fragments are the better. Any new line, any new letter, any better reading is a great happiness for scholars in this field," she said.

The new partnership is part of a drive by Google to have historical artifacts catalogued online, along with any other information.

"There are artifacts in boxes, in museum basements. We ask ourselves how much this stuff is available on the Internet. The answer is not a lot, and not enough," said Yossi Matias, an official from Google-Israel.

Google has worked to upload old books from European universities and pictures of archaeological finds from Iraq's national university. This project is different, Matias said, because access to the scrolls may spur new interpretations of the highly debated text and because the scrolls have a more universal appeal.

For the last 18 years, segments of the scrolls have been publicly displayed in museums around the world. At a recent exhibit in St. Paul, Minn., 15 fragments were shown.

Shor said a typical 3-month exhibit in the U.S. draws 250,000 people, illustrating just how much the scrolls have fascinated people.

"From the minute all of this will go online, there will be no need to expose the scroll anymore," Shor said. "Anyone in his office or on his couch will be able to click and see any scroll fragment or manuscript that they like."

Much mystery continues to surround the scrolls. No one knows who copied these ancient texts or how they got there. The scrolls include parts of the Hebrew Bible as well as treatises on communal living and apocalyptic war.

Over the years, the texts have sparked heated debates among researchers over their origins.

Some believe the Essenes, a monastic sect seen by some as a link to early Christianity, hid the scrolls during the Jewish revolt of the first century A.D. Others believe they were written in Jerusalem and stashed in caves at Qumran by Jewish refugees fleeing the Roman conquest of the city, also in the first century.