Tractors can kill. Farm safety for teens can save lives.

Loading...

| Gering, Neb.

Spend a little time with Ellen Duysen, and you’ll hear about the 7-year-old in South Dakota who suffocated in a grain wagon, the 14-year-old in Iowa who was killed when his family was changing a tractor wheel, or the gas can explosion in the same state that killed an 11-year-old.

Tragedies can happen in an instant, whether it’s a tractor hitting a hidden prairie dog hole or a farmer taking a moment to pick sweet corn and forgetting to set the parking brake.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAbout every three days, a child in the United States dies from an agriculture-related injury. One expert is cultivating lifesaving skills among teen farmers.

“Oh my gosh, you can become so saddened by the statistics,” Ms. Duysen says. “When you hear about these young farmers dying, it becomes a passion to keep them safe and healthy.”

Ms. Duysen is the sneakers-on-the-ground expert educating farmers in seven states across the Midwest and the Great Plains. As outreach coordinator for the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health in Omaha, Nebraska, she aims to cajole and inspire young farmers to embrace a “culture of safety” to protect them from the myriad hazards claiming the lives of far too many of their peers.

Ellen Duysen has driven 470 miles across Nebraska to get here, her windshield streaked with bugs. Her task: to impart safety lessons to a group of 14-year-old farmers in the state’s far west corner.

As outreach coordinator for the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health in Omaha, Ms. Duysen aims to cajole and inspire young farmers to embrace a “culture of safety” to protect them from the myriad hazards claiming the lives of far too many of their peers.

“What are you doing for fun this summer?” Ms. Duysen asks the five teenagers assembled at the Legacy of the Plains Museum in Gering, situated amid a landscape of buttes and two-lane roads.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onAbout every three days, a child in the United States dies from an agriculture-related injury. One expert is cultivating lifesaving skills among teen farmers.

“Raising show pigs,” 14-year-old Trey Carter pipes up.

“They’re naughty, aren’t they?” says Ms. Duysen, who has raised pigs herself and whose easygoing manner helps build rapport with the teens before she begins discussing the perils of farmwork.

Tragic statistics

About every three days, a child in the United States dies from an agriculture-related injury, and the agricultural sector leads the nation in the number of occupational fatalities for youths 17 and under, according to the National Children’s Center for Rural and Agricultural Health and Safety. Youths under age 16 have 12 times the risk of injuries involving all-terrain vehicles compared with adults, with some 300 children dying each year. Tractor accidents are the leading cause of death on farms, with roughly half of the vehicles lacking safety devices designed to prevent potentially fatal rollovers.

Ms. Duysen is the sneakers-on-the-ground expert educating farmers in seven states across the Midwest and the Great Plains. She is often accompanied by Pat, a male mannequin that she calls “gorgeous” and “delightful” and that helps her demonstrate personal protective equipment (PPE). Her home base at the University of Nebraska Medical Center is one of 12 centers around the country established by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Spend a little time with Ms. Duysen, and you’ll hear about the 7-year-old in South Dakota who suffocated in a grain wagon, the 14-year-old in Iowa who was killed when his family was changing a tractor wheel, or the gas can explosion in the same state that killed an 11-year-old. Tragedies can happen in an instant, whether it’s a tractor hitting a hidden prairie dog hole or a farmer taking a moment to pick sweet corn and forgetting to set the parking brake. “Oh my gosh, you can become so saddened by the statistics,” Ms. Duysen says. “When you hear about these young farmers dying, it becomes a passion to keep them safe and healthy.”

For the teens gathered at the museum in Gering, the day is a chance to earn a certificate that will allow them to legally drive tractors for people other than their parents, potentially enhancing their incomes. Federal law prohibits children under 16 from driving tractors unless their parents or legal guardians own the farm or unless they have certification. To gain certification, the teens will have to navigate a tractor with an attached trailer through a maze of orange cones set up in the museum parking lot.

With humor and heart

The teens’ skills will be evaluated by John Thomas, a local agricultural extension educator who typically advises farmers on growing sugar beets, beans, and other crops. Ms. Duysen always breaks the ice in her training sessions by asking, “What’s the weirdest food you’ve ever eaten?” Today’s replies – tuna casserole, seaweed, pickles submerged in Dr Pepper – are eclipsed by Mr. Thomas’ recipe for freezing a thousand live crickets and then sprinkling them with olive oil and salt before baking.

“Remind us never to come to your barbecue,” Ms. Duysen quips.

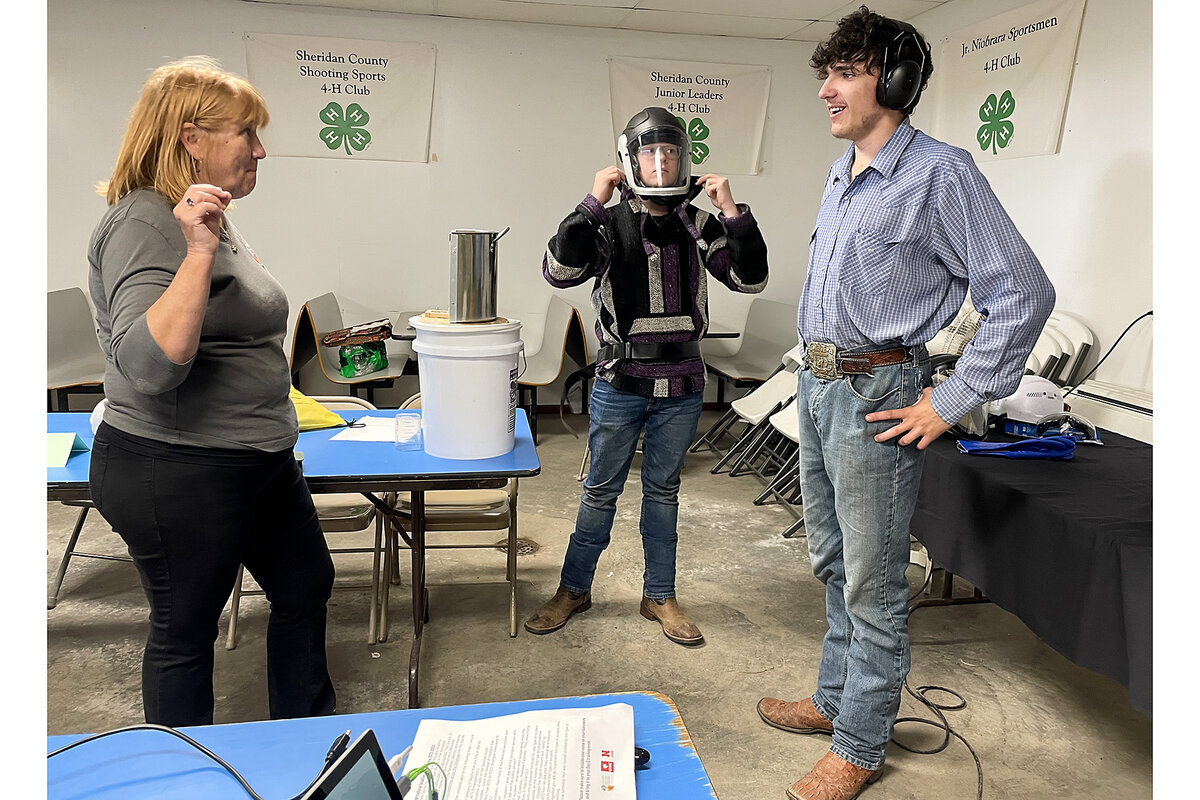

With sly humor and an energy belying four hours of sleep, she leans into hands-on learning, from a “stop the bleed” exercise with limbs made out of denim-wrapped pool noodles spattered with fake blood to a PPE fashion show in which the teens model noise-reducing earmuffs, face shields, and air-purifying respirators. “This is the bomb!” Ms. Duysen enthuses about the show.

She uses a miniature plastic farmer submerged in corn kernels to demonstrate how farmers can easily become engulfed in grain bins – what some call Midwestern quicksand. “We’ve lost three good Nebraska men this year already,” she says. “Do not go in that bin.”

She also asks her young charges how they might say no to a boss demanding that they do so. “Respectfully, sir, I’m too young to die,” volunteers Kenley Dehning, one of three young women in the group.

She and her fellow teens completed an online course before the training, including homework. Kenley tallied the state’s farm injuries and fatalities, noting gender disparities. “Heck yeah!” Ms. Duysen says in response to the research. Rainee Olson interviewed her uncle, who was 11 years old and eating lunch on a tractor when he accidentally hit the gear shift and fell off, crushing his arm and ankle and pulling off an ear. (“They sewed it back on,” Rainee reports.)

“An expert who has lived it”

Ms. Duysen is highly attuned to agricultural injuries, having had one herself. She was 26 and working for a veterinary pharmaceutical company in Colorado when she attempted to collect a blood sample from a heifer, who was secured in a head gate. As she leaned down, the heifer’s noggin collided with her own, knocking out her front teeth. The oral surgeon identified the heifer’s color by the red hairs in Ms. Duysen’s mouth. The experience changed Ms. Duysen’s approach. “I slowed down, for dang sure,” she says.

She grew up in Phoenix, the daughter of a psychologist and a newspaper editor, with four brothers (“it made me super tough”). After working as a microbiologist, she eventually decided to get a master’s degree in public health; providentially, the agricultural center opened six months later. She and her husband, Jack, a contractor, raised their three sons on a farm in Carson, Iowa.

In 2010, her center and four others launched the Telling the Story Project in which farmers reflect on their injuries and how they might have been prevented. The concept grew out of some 500 interviews Ms. Duysen and her now-retired mentor, Shari Burgus, conducted.

Jennifer Lincoln, associate director at NIOSH, credits Ms. Duysen for her role in the project, “calling it a very powerful tool.”

“There’s a difference between having an ‘expert’ and an expert who has lived it,” she adds.

This summer, Ms. Duysen also planned to set up shop at agricultural fairs like Husker Harvest Days, where she would entice grown-ups with free bucket hats – better sun protection than the baseball caps that many farmers wear. For lunch, she would grab a pork chop on a stick.

“If everyone was cautious, it would probably put us out of work,” she muses. There will be umpteen thousands of miles driven and who knows how many safety sessions with teenage farmers before then.