To fight wildfires in Pa., a time-tested tool makes a comeback: fire towers

| Somerset, Pa.

High atop a heavily wooded stretch of the Laurel Summit where ferns and may apples carpet the forest floor, it's easy to miss the narrow path off Fire Tower Road near Pennsylvania's Westmoreland-Somerset county line.

The road – a pair of rough dirt ruts through lush green woods – leads to a clearing where one of the region's last iconic fire towers stands watch over the seemingly endless mountains.

The 82-foot tower, a Depression-era vestige of the Civilian Conservation Corps' labor at Kooser State Park, owes its survival to a persistent park manager, a friends-of-the-park group and park staffers who recently raised funds and provided labor for its rehabilitation.

At one time, 449 of the storied towers – most were built in the 1920s and 1930s – stood watch over 3.2 million acres of Pennsylvnia state forest and gamelands. The towers were once considered the best line of defense against forest fires.

But their numbers dwindled – at least 380 are no longer standing – until recently, when they experienced a rebirth thanks to private efforts such as the one at Kooser and a separate $6 million project by the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources to restore or replace as many as 25 of the structures.

Although park enthusiasts view the hard-to-miss towers with nostalgia, the state's move to make them operational again stems from the high cost of using airplanes to monitor forests during the peak spring-to-fall fire season.

"One of the reasons for the renewed interest in fire towers is the rising cost of putting flights up. We pay between $500 and $1,000 an hour for observation time," said Mike Kern, the state's Forest Fire Protection Division chief.

Kern said construction of new towers, to be staffed by seasonal workers and volunteers, probably won't begin until next year. The exact number of towers and their locations will be determined after costs are tallied.

"We haven't done anything like this in Pennsylvania in decades," Kern said. "There's potentially up to 25 new towers. All the design work is completed, and the plan is to put a bid out for construction in the fall and hopefully start construction in the spring."

The project has gained national attention.

"The contract is very significant," said Keith Argow, national chairman of the Forest Fire Lookout Association, a group promoting the protection of fire towers across the country. "We've rarely seen such an impressive effort to renovate fire towers as a response to forest fires."

Argow agrees the structures are a crucial tool in protecting the nation's forests.

"We have seen that air patrols are effective, but they're only looking when they're flying by. Lookouts provide 24-hour protection," Argow said.

Although remote fire towers remain critical in bone-dry Western mountain states, their use has dramatically decreased elsewhere across the nation as forests have given way to development.

"Once we had 8,000 fire towers across the country. We have about 2,000 now, and of that only 700 are staffed. And more than 200 are staffed with volunteers," Argow said.

It was preserving a piece of park history that prompted Michael Mumau to begin looking into the abandoned fire tower at the top of Laurel Summit when he became manager for the Laurel Hill Park complex, which includes Laurel Hill, Kooser and Laurel Ridge state parks.

No one can remember exactly the last time the tower was used as a fire lookout, he said.

When Mumau started asking questions, he learned the state Fish and Boat Commission was deeded the tower in 1984 and used it as a mount for communications equipment.

Then the commission went to a new radio system, built a new tower and stopped using the old one.

When the Fish and Boat Commission agreed to sign the fire tower over to the state parks system, Mumau went to work, researching what it would take to make the tower a viable part of the park experience.

With the galvanized steel superstructure deemed sound, Jerry Eicher, president of the local chapter of Friends of the Park, penned a grant application to the state for materials to replace the rotting wooden steps and platforms.

Eicher, 79, of Mt. Pleasant Township, said he's been in love with the state parks since his parents started taking him there as a child.

The state gave the group a $4,000 grant, volunteers raised matching funds and park staff provided volunteer labor to restore the tower, which is now padlocked to deter vandalism.

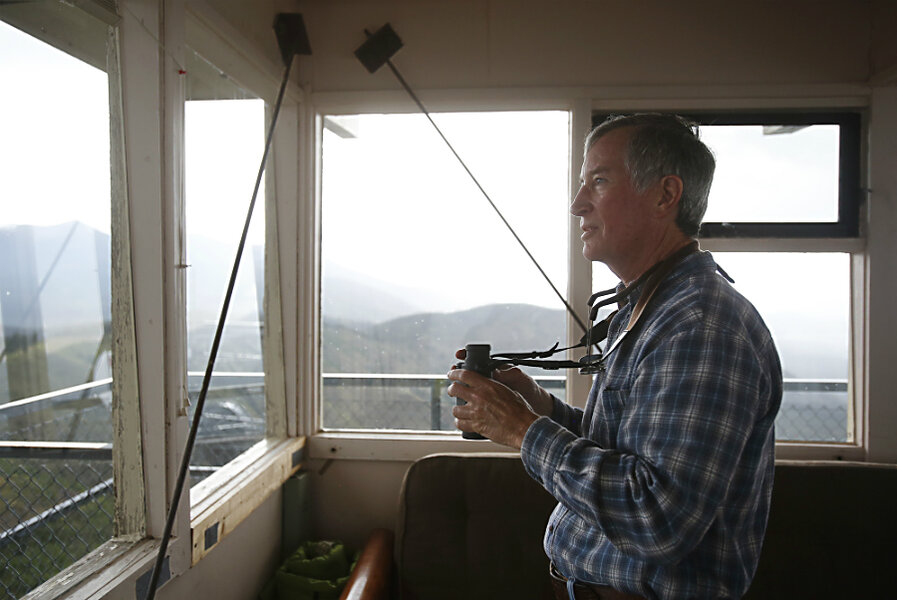

Visitors can climb the structure only under the supervision of park staffers during events held at various times of the year. From the tiny room at the top of six flights of steep oak stairs, they can take in a spectacular, miles-long view.

Argow and his national group hope the enthusiasm for restoring the towers spreads elsewhere in the nation.

"At least Pennsylvania never gave up on their fire towers," he said.