In Iran vote, conservatives set to retain power

Loading...

| Tehran

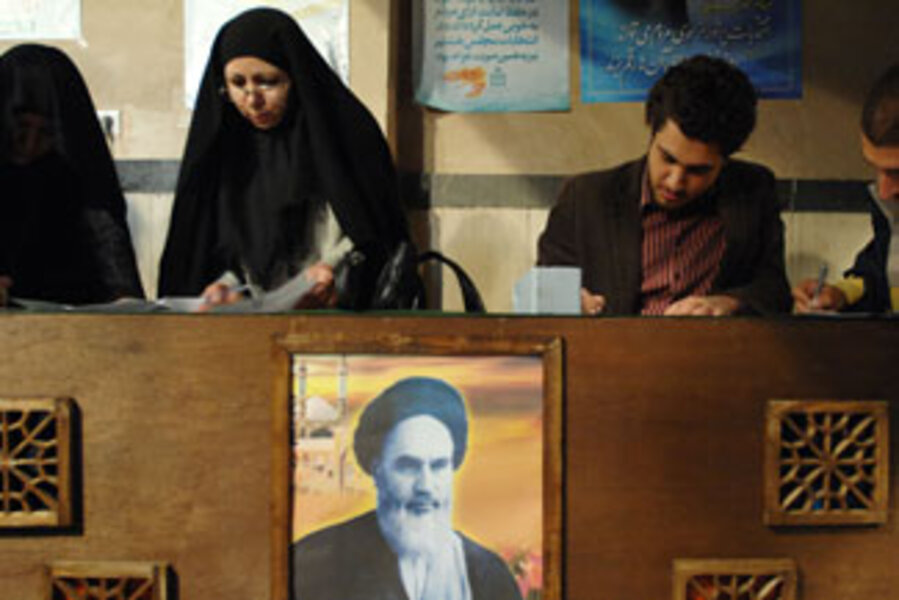

Iranians voted for a new parliament on Friday, in an election likely to reaffirm conservative dominance of Iranian politics. Authorities billed it as a blow against Western "enemies."

Chances for reformists were limited by design, and hard-liners loyal to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and other conservative factions were expected to keep their grip on the 290-seat parliament.

Final results won't be known for days. But the constant barrage of calls for mass turnout, on state television and from Iran's leaders, showed uncommon eagerness for a popular show of support from Iran's 44 million eligible voters.

"For our country and our nation this is a critical moment and day," said Iran's supreme religious leader Ayatollah Sayed Ali Khamenei, who usually stays above politics but has called Ahmadinejad's government the most popular in a century. "The election is a time that determines the fate of a nation."

Fatemeh Ghalampour, a small-claims judge and the chief of one of the 45,000 polling stations, couldn't agree more.

"Every single Iranian sees it as their duty to come and play a role in the future," says Ms. Ghalampour, her face framed by an all-black chador but also eyeliner and designer glasses, with several gold rings on her fingers. Those who choose not to vote, she says, "are unaware and lost. They are under the influence of others' negative views and don't use their brains."

But many reform-leaning Iranians on Friday said they saw no point in voting at all, since their ballot would not turn back hard-line control. Some 1,700 candidates, most of them reformists, were disqualified by hard-line vetting bodies, ensuring that the bulk of the 4,500 who remain are members of two main conservative camps.

A stone's throw from Ghalampour's polling station, half a dozen men – five older, one younger – enjoy tea in the morning sun. They refuse to vote, saying they've lost faith in politics. "All this is rubbish," says one of the men, nervously looking around and refusing to give his name. "It's all a lie ... everyone is sad because of the poor economy and high prices."

Conservatives seek large victory margin

Turnout has long been a critical benchmark in the Islamic Republic. Former president Mohammed Khatami's landslide victories in 1997 and 2001, with 80 percent and 67 percent turnout, drew upon a wave of expectations for change and easing of political and social restrictions that crushed conservative candidates.

Widespread anger at reform leaders for failing to keep those promises – and allowing conservatives to checkmate their progress at every turn – caused reformers, many of them young, to turn away from politics and punish their former heroes.

Today there is also widespread unhappiness with economic problems, and fierce criticism of Ahmadinejad's policy even from fellow conservatives. But the Islamic system does not want a repeat of the 2004 vote. Back then, conservatives wrested parliament back from reformists though turnout was just 51 percent nationwide, and only 40 percent in Tehran.

In Friday's election, conservatives viewed participation as a religious duty. Some even invoked the leader of Iran's 1979 Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

"It's so important that Khomeini said the parliament is the people's home, the head of the country; it decides the future," says a government official who gives his name as Hossein Karimi. He was voting in the hall where Khomeini once preached, in the traditional Jamaran neighborhood in north Tehran. "The people who defend the ideals of Imam Khomeini should enter [parliament]. They should be brave. They should be knowledgeable."

But around him other voters were conspicuously writing the names of Mr. Khatami's list of endorsed candidates onto the ballot.

"I want to decide for my future, and to let the world know we are smart enough to decide for ourselves," says Mohammad Amir Amighi, a computer software student. New rules, such as a short campaign and small-sized photos on posters, "really damaged the election," he says. But reformists can still win up to one-third of the vote, he estimates, if "there are no problems with the ballots and all is correct."

Reform leaders hope so. Khatami and former presidential candidate Mehdi Karroubi, among others, urged broad turnout to prevent ceding parliament to hard-liners without a fight – again.

"I'm not happy, but I am voting so that we can be happy in the future," says Hossein Mirfatah, a student of industrial engineering who, along with all his family, supports Khatami. "It's my country, and I want to live here free. I want to select my leaders.... People understand that when they don't vote they lose."

A message to the West: We're united

At Ghalampour's polling station in the Dezashib district of Tehran, there were five official observers from the Guardian Council – the same unelected conservative body that has final say on candidate qualifications. There were two more from the interior ministry, and two from the local governor's office, but no party observers.

Though polling stations are meant to be free of party materials, beneath some ballot boxes in Tehran on Friday were hung posters from the "morals committee" of the election commission, which showed a photograph of Ahmadinejad and a field of red flowers with the promise that "another spring is waiting."

The United States this week said it has "very low expectations that people will be able to actually express themselves."

Ahmadinejad took a decidedly different tone. "Our revolution means the presence of people," said the president after voting. "Parliament belongs to people and it should be a reflection of what they want."

But not everyone who voted came to the polls with conviction.

Teenage student Mona Shams, and her older sister Mehraveh, who works at the oil ministry, are two of them. Arriving at an ornately tiled mosque wearing bright lipstick and tight too-fashionable manteaux, they say they're voting only to have their identity cards stamped – to ensure no trouble later getting into university, or at work.

"Really we don't like this [regime], we don't accept it," says the younger Ms. Shams. "But we have to vote."

Petroleum engineer Nasser Fattahi holds a more nuanced view. He says he voted to send a message to the West of "unity," and defiance that sanctions "can slow down any development [in Iran], but they can't stop us."

"We try to elect the most experienced people," he says, taking a list of hard-line candidates from his pocket – conveniently provided by each party. "But voting does not mean everyone is satisfied with what is going on."