Hasty truce with Moqtada al-Sadr tests his sway in Baghdad stronghold

| BAGHDAD

A cease-fire deal to end seven weeks of fighting in Sadr City could provide the clearest test yet of just how much sway the anti-American Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr has over armed militants operating inside his sprawling bastion of support in Baghdad.

The truce, accepted by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki Saturday after being negotiated between the United Iraqi Alliance of ruling Shiite political parties and representatives of the Mr. Sadr's movement, is supposed to end the daily fighting that has claimed more than 1,000 lives in the vast Shiite slum.

The agreement allows government security forces to enter any part of Sadr City to arrest anyone with heavy weapons such as mortars and rocket launchers. Sadr has said his Mahdi Army militia is a defensive necessity, but that it does not use heavy weapons.

The truce was hastily reached as Mr. Maliki's government announced a new offensive in Mosul against forces affiliated with Al Qaeda in Iraq. Maliki has said since January that he would take the fight against Al Qaeda to the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, believed to be the group's last urban stronghold in Iraq. Some Iraqi government officials have suggested that Maliki wanted the battle with Shiite militias quieted before the Mosul offensive.

The Sadr City agreement does not call for the disarming or disbanding of the Mahdi Army, which was Maliki's demand that touched off fighting between his forces and the militia in late March. But it does call on Mahdi Army fighters to keep their weapons out of public view. All explosives planted in the streets of Sadr City are to be removed and the launching of rockets and mortars from the area – scores of which hit Iraqi and US government buildings in the Green Zone over recent weeks – is to stop.

Those attacks on the Green Zone drew the US military into the Sadr City fight, though US officials, including US Commander in Iraq Gen. David Petraeus, had encouraged Maliki to find a negotiated solution to the differences with Sadr. At the same time, US military officials have increasingly blamed the violence in Sadr City on "criminals," "gangs," and "special groups" trained and armed by Iran, and less on JAM, the acronym for the Sadr militia's Arabic name.

Several Iraqi officials said Iran was a party to the effort to stop the fighting in Sadr City, which Iranian officials have called warfare against Iraqi Shiites. If true, the Iranian involvement would follow a pattern set when Iranian officials played a key role in ending fighting between the Mahdi Army and Iraqi and US forces last month in the southern city of Basra.

And it would underscore Iran's growing political influence in Iraq.

On Sunday US military officials said negotiations on details of a truce were continuing between the government and Sadr representatives. But they said military operations in Sadr City had been "limited" as of Saturday night, based on expectations of an agreement.

Calling it "premature" to speak of a concluded accord, Rear Adm. Patrick Driscoll, spokesman for the Multi-National Forces in Iraq, said the US is "acting in support of the government of Iraq as they move ahead with discussions with elements of the Sadr movement." But he said that, as of Saturday, "We are limiting our operations, just as the Iraqi security forces are."

Admiral Driscoll did not comment on any agreement that would allow the Mahdi Army to keep its weapons, saying, "We have to wait to see the details." An armed Sadr militia could be problematic for the US, since Sadr has said his forces are authorized to act in "resistance" to the US presence.

It remains to be seen how successful the deal will be at ending the fighting, which assistance organizations warned last week was leading to a humanitarian crisis. Militants in the slum have demonstrated varying degrees of loyalty to Sadr, who is thought to be in Iran. If fighting and mortar-launching continue despite the truce, it could be a sign that Sadr has lost control of large factions within his militia.

In any case, the cease-fire agreement harbors the seeds of a continuing political conflict because it does not address the differences between the government and Sadr supporters over a political movement maintaining a militia.

Members of the Sadrist movement say the government's campaign against the Mahdi Army is a distraction from Maliki's true motivations: to stop the Sadrists' participation in provincial elections set for October, and to weaken Iraq's "nationalist forces" at a time when the government is negotiating a set of agreements on a long-term US military presence in Iraq.

"We are the last, the only resistance now to the occupation of Iraq," says Nassar al-Rubaie, leader of the Sadrist bloc in Iraq's parliament, the largest group in the 270-member body. "We want an Iraq free of all outside control, and an end to Iraqis fighting Iraqis."

Mr. Rubaie says Maliki launched what he calls "the siege of Sadr City" to weaken the Sadrists politically by creating a crisis and trying to turn their supporters against them. "He knows that forces loyal to our beliefs would sweep to power, so he's acting now to try to break our movement before these provincial elections."

The Sadrists say their principle objective remains a sovereign Iraq that is free from the "vicious circle" they say has made their country the battlefield in the American war on terror. "The Americans are here fighting Al Qaeda and terrorism and to make America more secure, while Al Qaeda is here to fight the infidels," says Liqaa al-Yaseen, a member of the Sadrist parliamentary bloc. "The result is terror for the Iraqi people caught in the middle of this war."

Dr. Yaseen says the only negotiation Iraq should have with the US is one setting a timetable for withdrawal. "Maliki wants to empty the field of any nationalist movement that opposes these long-term agreements."

The cleric's partisans in government are quick to point out what they say is the hypocrisy of Maliki's offensive to disarm Shiite militias.

"If Maliki truly intends to have no armed groups outside the Army and police, then why do we have the Sahwa?" Rubaie asks, referring to the "Sons of Iraq," the armed Sunni patrols created by the US military to help fight Al Qaeda-affiliated extremists.

"What about those militias that simply entered the Army or police, like Badr," he adds, referring to the militia, now largely absorbed into the Iraqi security forces, of Iraq's largest Shiite political party.

What really motivates Maliki, say the Sadrists, is his fear that with their anti-American message they will make large gains in the next round of elections.

But that public support may be less overwhelming than they assume if the growing impatience with conditions in Sadr City are any indication. Indeed, Iraqi officials say that it was the ire of Sadr City residents that prompted Sadr representatives to reach the cease-fire agreement.

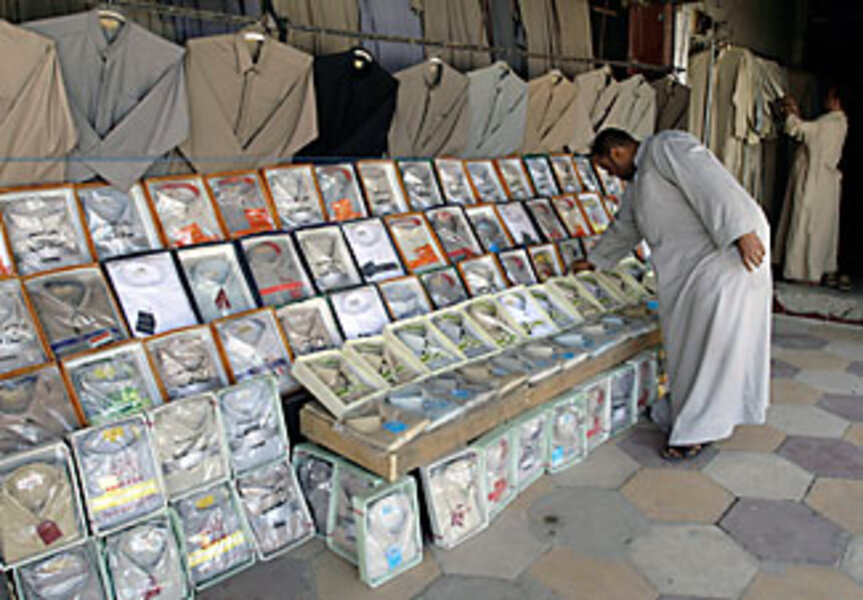

"We had Mahdi fighters shooting near our house, and then the Americans would come and shoot at them," says Abbas Alibi, a Sadr City street vendor who took his wife and four children to a camp of tents set up for displaced Sadr City residents at a Baghdad stadium. "We are not involved on either side of this fight, but it made staying in our home impossible."

Mr. Alibi says he finally decided to make his move when the government began encouraging residents of some parts of Sadr City to evacuate. "We thought surely that meant a big fight was coming."

Another father of a family sheltered in a nearby tent was more adamant. "Only government forces should be allowed to carry weapons, period," says the father of five, who requested anonymity because he has already been a target of Mahdi Army miltitants in his neighborhood. "All of the people of Sadr City are feeling that way now, so of course the militia doesn't like it."

Alibi says it will take more than the announcement of an agreement to get him to move his family home – despite the poor conditions in the temporary camp. "I'll have to go back first," he says, "and see for myself that the fighting really has stopped."