Egypt severly curtails press freedom ahead of elections

Loading...

| Cairo

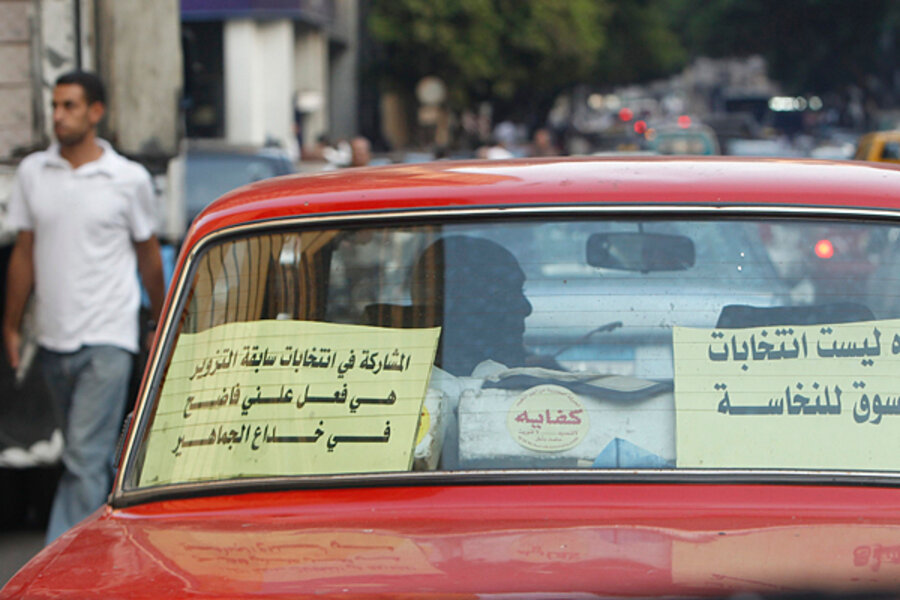

After a period of relative freedom, journalists in Egypt have become the targets of the harshest government crackdown in years, apparently aimed at silencing critical voices ahead of parliamentary elections next month and a presidential election next year.

The regime of President Hosni Mubarak, a staunch US ally, has shut down a string of television stations and imposed new regulations on newsgathering and telecommunications.

Critics say the attempt to muzzle opposition groups and reformists is intended to protect the 82-year-old Mubarak from public scrutiny of his 29-year grip on the Arab world's most populous nation.

Many observers said Mubarak's government had learned from the last elections, in 2005, when it allowed journalists wide latitude, and media outlets exposed electoral fraud by airing live footage of security forces beating voters and barring them from reaching ballot boxes.

"It is very alarming for us," said Mohamed Abdel Dayem, Middle East and North Africa program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based media watchdog. "Critical voices are being silenced one after the other."

The clampdown also has highlighted the links between Mubarak's regime and powerful businessmen who run media outlets that are nominally independent yet have silenced journalists who criticize the government.

Earlier this month, the firebrand journalist Ibrahim Eissa was fired from his post as editor in chief of the independent daily Al Dustour by the paper's new owners, one of whom is a business tycoon and a member of the Al Wafd opposition party. Also, a private satellite channel owned by another businessman took a television show that Mr. Eissa hosts off the air.

Eissa – who's written articles critical of Mubarak and his son and heir apparent, Gamal, and has raised the sensitive issue of Mubarak's health – told McClatchy that the government was openly flouting the Obama administration's calls for a fairer election process.

"The regime is interpreting Obama's advice and wishes in its own way," Eissa said. "It will not stop rigging the elections, but it will stop the talk concerning the rigging of the elections."

The defiant editor claimed that his former patrons were currying favor with the authorities, and that his dismissal may have bought the Wafd party more seats in the next parliament.

The moves marked a dramatic setback for journalists, who'd had greater freedom since 2004. Eissa credited former President George W. Bush, who urged Middle East allies to democratize, a form of direct pressure that the Obama administration so far has seemed reluctant to employ.

Egyptian journalists had pounced on the opportunity to criticize the state after years of censorship. Entrepreneurs saw it as a lucrative new market, as the public flocked to dynamic independent publications and satellite evening news programs that became mainstream Egypt's daily news digest.

"Despite all of George Bush's transgressions, his good deed was in calling for political reform in the Middle East," Eissa said.

However, Amr Hamzawy, an expert on Egyptian politics at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based research center, said that Mubarak's regime was merely "playing the game of being reform-oriented." During the Bush years, he said, Egyptian authorities hadn't yet figured out how to manage the flood of criticism.

The Mubarak regime's attitude was, "Let's see how much democratization an Arab government can handle without losing its grip on power," Hamzawy said.

The answer, apparently, is: Not very much.

Weeks before Eissa's firing, "Cairo Today," a popular talk show on a Saudi-owned satellite channel, was suddenly taken off the air, after an episode that criticized state media as excessively praising Gamal Mubarak.

Separately, Egypt's state satellite provider, Nilesat, shut down 17 private television channels, accusing them of inciting religious rivalries – for example, between Copts and Muslims – and violating lease regulations. Another 20 received warnings.

The country's telecommunications regulator revoked the permits of companies that provide satellite services for live broadcasts of street clashes involving security forces. It also imposed new rules requiring a permit to send mass text messages via mobile phones, a tool that was used in the past to mobilize voters or call on people to attend demonstrations. Only news agencies and political parties recognized by the state will be allowed permits.

Among those excluded is the Muslim Brotherhood, the leading opposition party, which is effectively banned by the state, and the National Association for Change, led by Mohamed ElBaradei, the former head of the UN nuclear watchdog agency, who returned to his home country to join the political opposition.

"It fundamentally cuts down the capability of opposition groups to mobilize demonstrations or to communicate with their constituencies, a key instrument, especially in the light of the emergency laws," Hamzawy said, referring to Egypt's 30-year-old law allowing arbitrary arrests and indefinite detention without trial.

The moves also come amid growing concern in Egypt over who'll succeed Mubarak, who disappeared from view in March when he underwent gallbladder surgery in Germany. His son Gamal, his likely choice for successor, is unpopular with the military and many older politicians.

A senior ruling party official, Alieddin Hilal, said last week that Mubarak would be its candidate for president next year. If he wins, it would be his sixth term.

(Naggar is a McClatchy special correspondent. Shashank Bengali contributed to this article.)

MORE FROM MCCLATCHY

Egyptian court cuts tycoon's sentence in Lebanese pop star's murder

Mitchell: Mideast peace accord can be inked in a year

Egypt's President Mubarak plans to run for 6th term

Read more: http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2010/10/26/102643/egypt-muzzles-media-in-advance.html#ixzz13ZpyJ6B5